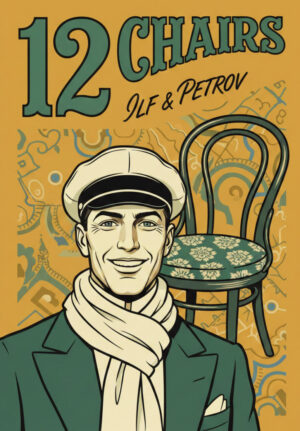

The Twelve Chairs, Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov: Read FREE Full Text Online (English Translation)

You can now read the full text for free of the Soviet era’s most widely read and quoted satirical masterpiece — The Twelve Chairs by the iconic co-authors Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov. This essential piece of reflective fiction Russian literature is available for online reading here in a high-quality English translation.

Dive into this captivating masterpiece and experience the hilarious misadventures of the “Great Schemer” Ostap Bender as he hunts for diamonds hidden in a set of chairs, delivering a biting critique of early Soviet life and greed. Start reading instantly without any download required. This exclusive free access is your gateway to the world of great Russian authors and their works.

You can also buy this book from us in the definitive paperback edition via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

The Twelve Chairs by Ilf and Petrov

Page Count: 574Year: 1928READ FREEProducts search “The Twelve Chairs” (1927) is a novel written almost a century ago, yet it feels as if it were just yesterday. Everyone quotes it, even those who haven’t read a single page or watched any of its numerous adaptations. Ostap Bender, the Great Schemer, has become a household name, with monuments erected to […]

€18.00 Login to Wishlist

First published in 1928 by the magazine “30 Days,”

then by the publishing house “Zemlya i fabrika.”

This book is in the public domain

Reprint by Publishing House №10

Publication date July 23, 2025

Translation from Russian

371 Pages, Font 12 pt, Bookman Old Style

Electronic edition, File size 2.0 MB

Cover design, Translate by Yulia Basharova

Copyright© Yulia Basharova 2025. All rights reserved

Table of Contents

PART ONE. THE STARGOROD LION

Chapter 1. Bezenchuk and “The Nymphs” 9

Chapter 2. The Demise of Madam Petukhova. 22

Chapter 3. The Mirror of the Sinner 34

Chapter 4. The Muse of Distant Wanderings. 43

Chapter 5. The Great Schemer 49

Chapter 7. The Traces of “Titanic” 70

Chapter 9. Where are Your Curls?. 94

Chapter 10. The Locksmith, the Parrot, and the Fortune-Teller 105

Chapter 11. The Alphabet of “The Mirror of Life” 121

Chapter 12. A Sultry Woman — A Poet’s Dream.. 140

Chapter 13. Breathe Deeper: You are Excited! 157

Chapter 14. “The Union of the Sword and Plow” 181

PART TWO. IN MOSCOW

Chapter 15. Amidst an Ocean of Chairs. 202

Chapter 16. Monk Berthold Schwarz’s Hostel 205

Chapter 17. Respect Mattresses, Citizens. 216

Chapter 18. The Furniture Museum.. 225

Chapter 19. European-Style Voting. 238

Chapter 20. From Seville to Grenada. 253

Chapter 21. The Execution. 270

Chapter 22. Ellochka the Cannibal 287

Chapter 23. Abessalom Vladimirovich Iznurenkov. 300

Chapter 24. The Automobile Club. 316

Chapter 25. Conversation with a Naked Engineer 328

Chapter 27. The Remarkable Do-Prov Basket 346

Chapter 28. The Hen And The Pacific Rooster 359

Chapter 29. The Author of “Gavriliada” 372

Chapter 30. At the Columbus Theater 383

Chapter 31. A Magical Night on the Volga. 403

PART THREE. MADAM PETUKHOVA’S TREASURE

Chapter 32. An Unclean Pair 415

Chapter 33. Expulsion from Paradise. 426

Chapter 34. The Interplanetary Chess Congress. 435

Chapter 36. View of the Malachite Puddle. 464

Chapter 38. Under the Clouds. 491

Chapter 39. The Earthquake. 503

PART ONE

THE STARGOROD LION

Chapter 1. Bezenchuk and “The Nymphs”

The district town of N had so many barbershops and funeral bureaus that it seemed the townspeople were born only to be shaved, get a haircut, freshen their heads with vegetaline, and then immediately die. In reality, people in the district town of N were born, shaved, and died quite rarely. Life in town N was exceptionally quiet. Spring evenings were intoxicating, the mud shimmered like anthracite under the moon, and all the town’s youth were so deeply in love with the secretary of the communal workers’ local committee that it hindered their ability to collect membership dues.

Questions of love and death didn’t concern Ippolit Matveevich Vorobyaninov, though he dealt with these matters in his official capacity from nine in the morning until five in the evening daily, with a half-hour break for breakfast.

In the mornings, after drinking his portion of hot milk, served by Klavdia Ivanovna in a frosty, veined glass, he would step out of the dimly lit little house onto the spacious street named after Comrade Gubernsky, full of wondrous spring light. It was one of the most pleasant streets found in district towns. To the left, through wavy greenish glass, the coffins of the “Nymph” funeral bureau shimmered. To the right, behind small windows with crumbling putty, lay the gloomy, dusty, and dull oak coffins of Bezenchuk, the coffin maker. Further on, “Hairdresser Pierre and Konstantin” promised their clients “nail care” and “home perms.” Even further, there was a hotel with a barbershop, and beyond it, in a large vacant lot, stood a fawn calf gently licking a rusty sign leaning against a solitary gate:

FUNERAL OFFICE “WELCOME”

Though there were many funeral businesses, their clientele was not wealthy. “Welcome” had gone bankrupt three years before Ippolit Matveevich settled in town N, and Master Bezenchuk drank heavily and even once tried to pawn his best display coffin.

People in town N died rarely, and Ippolit Matveevich knew this better than anyone, as he worked in the civil registry office, where he oversaw the registration of deaths and marriages.

The desk where Ippolit Matveevich worked resembled an old tombstone. Its left corner had been destroyed by rats. Its flimsy legs trembled under the weight of plump, tobacco-colored folders filled with records, from which one could glean all information about the genealogies of town N’s inhabitants and the “genealogical firewood” that had grown on the meager district soil.

On Friday, April 15, 1927, Ippolit Matveevich woke up as usual at half past seven and immediately poked his nose into his old-fashioned pince-nez with a gold bridge. He didn’t wear spectacles. Once, deciding that wearing a pince-nez was unhygienic, Ippolit Matveevich went to an optician and bought rimless glasses with gilded shafts. He liked the glasses at first, but his wife (this was shortly before her death) found that in them he looked exactly like Milyukov, and he gave the glasses to the janitor. The janitor, though not nearsighted, got used to the glasses and wore them with pleasure.

“Bonjour!” Ippolit Matveevich sang to himself as he swung his legs out of bed. “Bonjour” indicated that Ippolit Matveevich had woken up in a good mood. Saying “Guten Morgen” upon waking usually meant that his liver was acting up, that fifty-two years was no joke, and that the weather was damp today. Ippolit Matveevich slipped his lean legs into pre-war, ready-made trousers, tied them at the ankles with ribbons, and plunged into short, soft boots with narrow square toes. Five minutes later, Ippolit Matveevich was adorned in a moon-colored waistcoat sprinkled with tiny silver stars and an iridescent luster jacket. Wiping the last dewdrops from his gray hair after washing, Ippolit Matveevich ferociously twitched his mustache, hesitantly touched his rough chin, brushed his short-cropped, “aluminum” hair, and, smiling courteously, moved to greet his entering mother-in-law, Klavdia Ivanovna.

“Ippole-et,” she boomed, “today I had a bad dream.”

The word “dream” was pronounced with a French accent.

Ippolit Matveevich looked down at his mother-in-law. He stood one hundred and eighty-five centimeters tall, and from such a height, it was easy and comfortable for him to regard his mother-in-law with some disdain. Klavdia Ivanovna continued:

“I saw the deceased Marie with her hair down and in a golden sash.”

From the booming sounds of Klavdia Ivanovna’s voice, the cast-iron lamp with its “core,” “shot,” and dusty glass trinkets trembled.

“I’m very worried. I’m afraid something might happen.”

The last words were uttered with such force that the bob of hair on Ippolit Matveevich’s head swayed from side to side. He wrinkled his face and distinctly said:

“Nothing will happen, Maman. Have you paid for the water yet?”

It turned out they hadn’t. The galoshes hadn’t been washed either. Ippolit Matveevich didn’t like his mother-in-law. Klavdia Ivanovna was foolish, and her advanced age offered no hope that she would ever become wiser. She was exceptionally stingy, and only Ippolit Matveevich’s poverty prevented this captivating feeling from fully blossoming. Her voice had such power and depth that Richard the Lionheart, whose shouts, as is known, made horses crouch, would have envied it. And besides—which was the most dreadful thing—Klavdia Ivanovna had dreams. She always had them. She dreamed of girls in sashes, horses embroidered with yellow dragoon piping, janitors playing harps, archangels in sheepskin coats walking around at night with rattles in their hands, and knitting needles that jumped around the room by themselves, making a distressing clatter. Klavdia Ivanovna was an empty old woman. In addition to everything, a mustache had grown under her nose, and each hair of the mustache resembled a shaving brush.

Ippolit Matveevich, slightly irritated, left the house.

At the entrance to his dilapidated establishment stood Bezenchuk, the coffin maker, leaning against the doorframe with crossed arms. From the systematic failures of his commercial ventures and long-term consumption of alcoholic beverages, the master’s eyes were bright yellow, like a cat’s, and burned with an unquenchable fire.

“Honor to the dear guest!” he rattled off, seeing Ippolit Matveevich. “Good morning!”

Ippolit Matveevich politely raised his stained castor hat.

“How is your dear mother-in-law’s health, may I ask?”

“Mm-mm-mm,” Ippolit Matveevich replied vaguely, and, shrugging his straight shoulders, proceeded onwards.

“Well, God grant her good health,” Bezenchuk said bitterly, “such losses we incur, confound it all!”

And again, he crossed his arms over his chest and leaned against the door.

At the gates of the “Nymph” funeral bureau, Ippolit Matveevich was detained again.

There were three owners of “Nymph.” They bowed in unison to Ippolit Matveevich and in chorus inquired about his mother-in-law’s health.

“She’s well, well,” Ippolit Matveevich replied, “what could happen to her! Today she saw a golden girl, with her hair down. Such was her vision in a dream.” The three “nymphs” exchanged glances and sighed loudly. All these conversations delayed Ippolit Matveevich on his way, and he, contrary to habit, arrived at work when the clock hanging above the slogan “Do your business – and leave” showed five past nine.

Ippolit Matveevich was nicknamed Maciste at the office because of his tall stature, and especially his mustache, although the real Maciste had no mustache.

Taking a blue felt cushion from his desk drawer, Ippolit Matveevich placed it on the table, aligned his mustache correctly (parallel to the table line), and sat on the cushion, rising slightly above his three colleagues. Ippolit Matveevich didn’t fear hemorrhoids; he feared wearing out his trousers and therefore used the blue felt.

Two young people — a man and a young woman — shyly observed all the manipulations of the Soviet clerk. The man, in a cotton-padded broadcloth jacket, was completely overwhelmed by the office atmosphere, the smell of alizarin ink, the clock that often breathed heavily, and especially the stern poster “Do your business – and leave.” Although the man in the jacket hadn’t even begun his business, he already wanted to leave. It seemed to him that the matter he had come for was so insignificant that it was shameful to bother such a prominent gray-haired citizen as Ippolit Matveevich about it. Ippolit Matveevich himself understood that the visitor’s business was small, that it could wait, and so, opening binder No. 2 and twitching his cheek, he delved into the papers. The young woman, in a long jacket trimmed with shiny black braid, whispered to the man and, warming with shame, slowly began to move towards Ippolit Matveevich.

“Comrade,” she said, “where here…”

The man in the jacket sighed happily and, unexpectedly to himself, bellowed:

“To get married!”

Ippolit Matveevich looked attentively at the railing behind which the couple stood.

“Birth? Death?”

“To get married,” the man in the jacket repeated, looking around in confusion.

The young woman snickered. The matter was well underway. Ippolit Matveevich, with the dexterity of a conjurer, set to work. He recorded the names of the newlyweds in his old-womanish handwriting in thick books, sternly questioned the witnesses whom the bride had run out to fetch from the courtyard, breathed long and tenderly on the square stamps, and, rising slightly, pressed them onto the worn passports. Accepting two rubles from the newlyweds and issuing a receipt, Ippolit Matveevich said with a smirk, “For the performance of the sacrament,” and rose to his full splendid height, habitually puffing out his chest (he used to wear a corset). Thick yellow rays of sun lay on his shoulders like epaulets. He looked somewhat comical, but extraordinarily solemn. The biconcave lenses of his pince-nez shone with a white spotlight. The young couple stood like lambs.

“Young people,” Ippolit Matveevich declared grandiloquently, “allow me to congratulate you, as was formerly said, on your lawful marriage. It is very, very pleasant to see young people like yourselves, who, holding hands, go towards the achievement of eternal ideals. Very, very pleasant!”

Having delivered this tirade, Ippolit Matveevich shook the newlyweds’ hands, sat down, and, quite pleased with himself, continued reading papers from binder No. 2.

At the next desk, the clerks grunted into their inkwells.

The calm flow of the workday began. No one disturbed the death and marriage registration desk. Through the window, citizens could be seen, shivering from the spring chill, dispersing to their homes. Exactly at noon, a rooster crowed in the “Plow and Hammer” cooperative. No one was surprised. Then came the metallic quacking and clatter of a motor. A thick cloud of purple smoke rolled out from Comrade Gubernsky Street. The clatter intensified. Soon, the outlines of the district executive committee’s car, State No. 1, with a tiny radiator and bulky body, appeared from behind the smoke. The car, churning in the mud, crossed Staropanskaya Square and, swaying, disappeared into the poisonous smoke. The clerks stood at the window for a long time, commenting on the incident and linking it to a possible staff reduction. After a while, Master Bezenchuk carefully walked across the wooden boardwalks. He wandered around the town all day, inquiring if anyone had died.

The workday was drawing to a close. On the nearby yellowish-white bell tower, the bells rang with all their might. The windows rattled. Jackdaws flew from the belfry, held a meeting above the square, and flew away. The evening sky froze over the deserted square. It was time for Ippolit Matveevich to leave. Everything that was to be born that day had been born and recorded in the thick books. All those wishing to be married had been married and also recorded in the thick books. And there was, to the clear ruin of the undertakers, not a single death. Ippolit Matveevich put away his papers, hid the felt cushion in the drawer, fluffed his mustache with a comb, and was just about to leave, dreaming of a fiery soup, when the office door swung open, and Bezenchuk, the coffin maker, appeared on its threshold.

“Honor to the dear guest,” Ippolit Matveevich smiled. “What do you have to say?”

Although the master’s wild face glowed in the encroaching twilight, he couldn’t say anything.

“Well?” Ippolit Matveevich asked more strictly.

“Does ‘Nymph,’ confound it, give good merchandise?” the coffin maker mumbled vaguely. “Can it truly satisfy a customer? A coffin — it takes so much wood…”

“What?” Ippolit Matveevich asked.

“Well, ‘Nymph’… Three families live off that one little trade. Their material isn’t the same, and the finishing is worse, and the brush is flimsy, confound it. But I’m an old firm. Founded in nineteen hundred seven. My coffin — it’s a gem, choice, amateur…”

“What, have you gone mad?” Ippolit Matveevich asked meekly and moved towards the exit. “You’ll go crazy among coffins.”

Bezenchuk obligingly pulled the door open, let Ippolit Matveevich pass, and then followed him, trembling as if with impatience.

“Back when ‘Welcome’ was around, now that was something! No firm, not even in Tver itself, could stand against their glaze — confound it. But now, frankly, there’s no better product than mine. Don’t even look.”

Ippolit Matveevich turned around angrily, glared at Bezenchuk for a second, and walked a little faster. Although no unpleasantries had occurred at work that day, he felt quite nasty.

The three owners of “Nymph” stood by their establishment in the same poses in which Ippolit Matveevich had left them that morning. It seemed they hadn’t spoken a word to each other since then, but a striking change in their faces, a mysterious satisfaction dimly flickering in their eyes, showed that they knew something significant.

At the sight of his commercial rivals, Bezenchuk desperately waved his hand, stopped, and whispered after Vorobyaninov:

“I’ll let it go for thirty-two rubles.”

Ippolit Matveevich grimaced and quickened his pace.

“On credit, if you like,” Bezenchuk added. The three owners of “Nymph,” however, said nothing. They silently followed Vorobyaninov, continuously doffing their caps as they walked and bowing politely.

Thoroughly angered by the undertakers’ foolish persistence, Ippolit Matveevich ran up the porch steps faster than usual, irritably scraped the mud off his boots on the step, and, feeling intense pangs of hunger, entered the hallway. Father Fyodor, the priest of the Church of Flor and Lavr, came out of the room towards him, radiating heat. Picking up his cassock with his right hand and ignoring Ippolit Matveevich, Father Fyodor hurried towards the exit.

It was then that Ippolit Matveevich noticed the excessive cleanliness, a jarring new disorder in the arrangement of the sparse furniture, and felt a tickling in his nose from a strong medicinal scent. In the first room, Ippolit Matveevich was met by his neighbor, agronomist Kuznetsova. She whispered and waved her hands:

“She’s worse; she just confessed. Don’t thump your boots.”

“I’m not thumping,” Ippolit Matveevich answered meekly. “What happened?”

Madam Kuznetsova pursed her lips and pointed towards the door of the second room:

“A severe heart attack.” And, repeating clearly someone else’s words that she liked for their significance, she added:

“The possibility of a fatal outcome is not excluded. I’ve been on my feet all day today. I came this morning for the meat grinder, looked — the door was open, no one in the kitchen, no one in this room either, well, I thought Klavdia Ivanovna went for flour for kulich. She was going to just now. Flour now, you know, if you don’t buy it in advance…”

Madam Kuznetsova would have talked for a long time about flour, about the high prices, and about how she found Klavdia Ivanovna lying by the tiled stove in a completely lifeless state, but a groan from the next room painfully struck Ippolit Matveevich’s ear. He quickly crossed himself with a slightly numb hand and went into his mother-in-law’s room.

Chapter 2. The Demise of Madam Petukhova

Klavdia Ivanovna lay on her back, one hand tucked under her head. Her head was adorned with an intensely apricot-colored cap, which had been fashionable in some year when ladies wore “chantecler” and were just beginning to dance the Argentine “tango.”

Klavdia Ivanovna’s face was solemn but expressed absolutely nothing. Her eyes stared at the ceiling.

“Klavdia Ivanovna!” Vorobyaninov called out. His mother-in-law’s lips moved quickly, but instead of the trumpet-like sounds Ippolit Matveevich was accustomed to, he heard a quiet, thin, and pitiful moan that made his heart stir. A shining tear unexpectedly and quickly rolled from her eye and, like mercury, slid across her face.

“Klavdia Ivanovna,” Vorobyaninov repeated, “what’s wrong?”

But again, he received no answer. The old woman closed her eyes and tilted slightly onto her side.

The agronomist quietly entered the room and led him away by the hand, like a boy being taken to bathe.

“She’s fallen asleep. The doctor said not to disturb her. My dear, go to the pharmacy. Here’s the receipt, and find out how much ice bags cost.” Ippolit Matveevich completely submitted to Madam Kuznetsova, sensing her undeniable superiority in such matters.

It was a long way to the pharmacy. Like a schoolboy, clutching the prescription in his fist, Ippolit Matveevich hurried out into the street.

It was almost dark. Against the fading twilight, the scrawny figure of Bezenchuk, the coffin maker, could be seen, leaning against a fir gate, eating bread and onions. Squatting nearby were the three “nymphs,” licking their spoons and eating buckwheat porridge from a cast-iron pot. At the sight of Ippolit Matveevich, the undertakers straightened up like soldiers. Bezenchuk shrugged his shoulders indignantly and, extending a hand in the direction of his competitors, grumbled:

“They’re getting in the way, confound them. In the middle of Staropanskaya Square, by the bust of the poet Zhukovsky with the inscription carved on its pedestal: ‘Poetry is God in the holy dreams of the earth,’ lively conversations were taking place, sparked by the news of Klavdia Ivanovna’s serious illness. The general opinion of the assembled townspeople was that ‘we’ll all end up there’ and that ‘God gave, and God took away.'”

The hairdresser “Pierre and Konstantin,” who readily answered to the name “Andrei Ivanovich,” didn’t miss the opportunity to display his medical knowledge, gleaned from the Moscow magazine “Ogonyok.”

“Modern science,” Andrei Ivanovich said, “has reached the impossible. Take, for example, if a client gets a pimple on his chin. Before, it could lead to blood poisoning, but now in Moscow, they say — I don’t know if it’s true or not — each client gets a separate sterilized brush.”

The citizens sighed at length.

“You’re exaggerating a bit there, Andrei…”

“Where have you ever seen a separate brush for every person? He’ll invent anything!”

The former proletarian of intellectual labor, now stallholder Prusis, even became agitated:

“Excuse me, Andrei Ivanovich, according to the last census, Moscow has more than two million inhabitants? So, that means more than two million brushes are needed? Quite original.”

The conversation was growing heated and who knows where it would have led if Ippolit Matveevich hadn’t appeared at the end of Osypnaya Street.

“He ran to the pharmacy again. Things are bad, then.”

“The old woman will die. No wonder Bezenchuk is running around town beside himself.”

“What does the doctor say?”

“What doctor! Are those in the health insurance fund even doctors? They’d cure a healthy man to death!”

“Pierre and Konstantin,” who had long been itching to make a medical statement, spoke, looking around cautiously:

“Now all the power is in hemoglobin.” Having said this, “Pierre and Konstantin” fell silent. The townspeople also fell silent, each pondering in their own way the mysterious powers of hemoglobin.

When the moon rose and its minty light illuminated the miniature bust of Zhukovsky, a short swear word written in chalk could be clearly distinguished on its copper back.

For the first time, such an inscription appeared on the bust on June 15, 1897, the night immediately following the monument’s unveiling. And no matter how hard the police, and later the militia, tried, the abusive inscription was meticulously renewed every day.

In the wooden houses with external shutters, samovars were already singing. It was dinner time. The citizens didn’t waste time and dispersed. The wind began to blow.

Meanwhile, Klavdia Ivanovna was dying. She would alternately ask for a drink, then say that she needed to get up and fetch Ippolit Matveevich’s formal boots, which were out for repair, then complain about the dust, which, according to her, was suffocating, then ask for all the lamps to be lit.

Ippolit Matveevich, who was already tired of worrying, paced the room. Unpleasant household thoughts crept into his mind. He thought about having to get an advance from the mutual aid fund, running to fetch the priest, and answering condolence letters from relatives. To distract himself a bit, Ippolit Matveevich went out onto the porch. In the green moonlight stood Bezenchuk, the coffin maker.

“So, what do you command, Mr. Vorobyaninov?” the master asked, pressing his cap to his chest.

“Well, I suppose so,” Ippolit Matveevich replied gloomily.

“And ‘Nymph,’ confound it, does it really offer good merchandise!” Bezenchuk became agitated.

“Oh, go to hell! I’m tired of you!”

“I’m just saying. About the brushes and the brocade. How should I do it, confound it? First-class, prima? Or what?”

“Without any brushes or brocade. A simple wooden coffin. Pine. Understand?”

Bezenchuk put a finger to his lips, indicating that he understood everything, turned around, and, balancing his cap but still swaying, went on his way. Only then did Ippolit Matveevich notice that the master was mortally drunk.

Ippolit Matveevich again felt extraordinarily nasty inside. He couldn’t imagine how he would enter the empty, cluttered apartment. It seemed to him that with his mother-in-law’s death, the small comforts and habits he had painstakingly created for himself after the revolution, which had stolen his great comforts and broad habits, would disappear. “Marry?” Ippolit Matveevich thought. “Whom? The police chief’s niece, Varvara Stepanovna, Prusis’s sister? Or perhaps hire a housekeeper? No way! She’d drag me through the courts. And it’s expensive too.”

Life immediately turned black in Ippolit Matveevich’s eyes. Full of indignation and disgust for everything in the world, he returned to the house.

Klavdia Ivanovna was no longer delirious. Lying high on the pillows, she looked at Ippolit Matveevich, who had entered, quite meaningfully and, it seemed to him, even sternly.

“Ippolit,” she whispered distinctly, “sit beside me. I must tell you…”

Ippolit Matveevich sat down reluctantly, peering at his mother-in-law’s emaciated, mustachioed face. He tried to smile and say something encouraging. But his smile turned out to be wild, and no encouraging words came to mind. Only an awkward squeak escaped Ippolit Matveevich’s throat.

“Ippolit,” his mother-in-law repeated, “do you remember our drawing-room suite?”

“Which one?” Ippolit Matveevich asked with a solicitousness only possible towards very ill people.

“That one… Upholstered in English chintz…”

“Ah, that was in my house?”

“Yes, in Stargorod…”

“I remember, I remember perfectly… A sofa, a dozen chairs, and a round table with six legs. The furniture was excellent, from Gambs… Why did you recall it?”

But Klavdia Ivanovna couldn’t answer. Her face slowly began to take on a copper sulfate color. For some reason, Ippolit Matveevich also felt his breath catch. He distinctly recalled the drawing-room in his mansion, the symmetrically arranged walnut furniture with curved legs, the polished waxed floor, the old brown piano, and the oval black frames with daguerreotypes of dignified relatives on the walls.

Then Klavdia Ivanovna, in a wooden, indifferent voice, said:

“I sewed my diamonds into the seat of a chair.” Ippolit Matveevich glanced at the old woman.

“What diamonds?” he asked mechanically, but immediately caught himself. “Weren’t they confiscated then, during the search?”

“I hid the diamonds in a chair,” the old woman stubbornly repeated.

Ippolit Matveevich jumped up and, looking at Klavdia Ivanovna’s stone-like face, illuminated by the kerosene lamp, realized that she was not delirious.

“Your diamonds!” he cried, startled by the force of his own voice. “In a chair! Who put that idea in your head? Why didn’t you give them to me?”

“How could I give you the diamonds when you squandered my daughter’s estate?” the old woman said calmly and maliciously.

Ippolit Matveevich sat down and immediately stood up again. His heart noisily sent streams of blood throughout his body. His head began to throb.

“But you took them out, didn’t you? Are they here?” The old woman shook her head negatively.

“I didn’t have time. You remember how quickly and unexpectedly we had to flee. They remained in the chair that stood between the terracotta lamp and the fireplace.”

“But this is madness! How much you resemble your daughter!” Ippolit Matveevich cried out at the top of his voice.

And no longer bothered by being at the bedside of a dying woman, he pushed a chair aside with a crash and scurried around the room. The old woman indifferently watched Ippolit Matveevich’s actions.

“But do you even imagine where these chairs might have ended up? Or do you perhaps think they are quietly standing in my drawing-room, waiting for you to come and collect your r-regalia?” The old woman did not answer.

From anger, the civil registry clerk’s pince-nez fell from his nose and, flashing its golden bridge by his knees, crashed to the floor.

“What? To sew diamonds worth seventy thousand into a chair! Into a chair on which God knows who is sitting!…”

Here Klavdia Ivanovna sobbed and moved her entire body towards the edge of the bed. Her hand, describing a semicircle, tried to grasp Ippolit Matveevich, but immediately fell back onto the quilted purple blanket.

Ippolit Matveevich, yelping with fear, rushed to his neighbor.

“She’s dying, I think!”

The agronomist diligently crossed herself and, not hiding her curiosity, ran into Ippolit Matveevich’s house along with her husband, a bearded agronomist. Vorobyaninov himself stumbled bewildered into the city garden.

While the agronomist couple and their servant tidied the deceased’s room, Ippolit Matveevich wandered through the garden, bumping into benches and mistaking couples stiff from early spring love for bushes.

God knows what was going on in Ippolit Matveevich’s head. Gypsy choirs sounded, busty ladies’ orchestras continuously played “tango-amapa,” and he envisioned the Moscow winter and a black, long-legged trotter contemptuously snorting at pedestrians. Many things appeared to Ippolit Matveevich: intoxicatingly expensive orange long underwear, a lackey’s devotion, and a possible trip to Cannes.

Ippolit Matveevich walked more slowly and suddenly stumbled over the body of Bezenchuk, the coffin maker. The master was sleeping, lying in his sheepskin coat across the garden path. The jolt woke him, he sneezed, and quickly stood up.

“Don’t trouble yourself, Mr. Vorobyaninov,” he said warmly, as if continuing the conversation they had started earlier. “A coffin — it loves work.”

“Klavdia Ivanovna has died,” the client informed him.

“Well, may she rest in peace,” Bezenchuk agreed. “So, the old woman passed away… Old women, they always pass away… Or give up their soul to God — it depends on the old woman. Yours, for example, is small and stout — so she passed away. But, for example, a larger and leaner one — she’s considered to give up her soul to God…”

“What do you mean, ‘considered’? Who considers this?”

“We do. The masters. For example, you, a prominent man, tall, though thin. You, it’s considered, if, God forbid, you die, that you ‘kicked the bucket.’ And a tradesman, of the former merchant guild, he, it’s said, ‘ordered a long life.’ And if someone of a lower rank, a janitor, for example, or a peasant, about him they say: ‘he flipped over’ or ‘stretched his legs.’ But when the most powerful die, railway conductors or someone from the authorities, it’s considered that they ‘gave up the ghost.’ That’s what they say about them: ‘Our man, did you hear, gave up the ghost.'”

Stunned by this strange classification of human deaths, Ippolit Matveevich asked:

“Well, and when you die, what will the masters say about you?”

“I’m a small man. They’ll say: ‘Bezenchuk croaked.’ And nothing more. And he added sternly:

“It’s impossible for me to ‘give up the ghost’ or ‘kick the bucket’: my build is small… And about the coffin, Mr. Vorobyaninov? Are you really going to have it without brushes and brocade?”

But Ippolit Matveevich, again immersed in dazzling dreams, answered nothing and moved forward. Bezenchuk followed him, counting something on his fingers and, as usual, muttering.

The moon had long vanished. It was winter-cold. The puddles were again covered with brittle, waffle-like ice. On the street named after Comrade Gubernsky, where the companions had emerged, the wind fought with the signs. From the direction of Staropanskaya Square, with the sounds of a lowering blind, a fire brigade on thin horses rode out.

The firefighters, dangling their canvas-clad legs from the platform, shook their helmeted heads and sang in deliberately unpleasant voices:

“Glory to our fire chief, Glory to our dear Comrade Nasosov!”

“They were at Kolka’s wedding, the fire chief’s son,” Bezenchuk said indifferently, scratching his chest under his sheepskin coat. “So, really, without brocade and without anything?”

Just then, Ippolit Matveevich had already decided everything. “I’ll go,” he decided, “I’ll find them. And then we’ll see.” And in his diamond-filled dreams, even his deceased mother-in-law seemed dearer to him than she had been. He turned to Bezenchuk:

“To hell with you! Do it! Brocade! With brushes!”

Chapter 3. The Mirror of the Sinner

After confessing the dying Klavdia Ivanovna, Father Fyodor Vostrikov, priest of the Church of Flor and Lavr, left Vorobyaninov’s house in a state of complete agitation. He walked all the way to his apartment, looking around distractedly and smiling shyly. By the end of his journey, his absent-mindedness had reached such a degree that he almost ended up under the district executive committee’s car, State No. 1. Emerging from the purple fog emitted by the infernal machine, Father Vostrikov became utterly distraught and, despite his venerable clerical rank and middle age, covered the rest of the way at a frivolous half-gallop.

Matushka Katerina Alexandrovna was setting the table for supper. Father Fyodor, on days free from all-night vigils, liked to dine early. But now, taking off his hat and his warm, padded cassock, the priest quickly slipped into the bedroom, much to Matushka’s surprise, locked himself in, and began to hum “It is Truly Meet” in a muffled voice. Matushka sat down on a chair and whispered fearfully:

“He’s started something new…” Father Fyodor’s impetuous soul knew no peace. It had never known it. Not when he was a seminary student, Fedia, nor when he was a mustachioed seminarian, Fyodor Ivanovich. After leaving the seminary for the university and studying at the law faculty for three years, Vostrikov, in 1915, feared possible mobilization and once again pursued a spiritual path. First, he was ordained a deacon, and then consecrated as a priest and appointed to the district town of N. And always, in all stages of his spiritual and civil career, Father Fyodor remained a covetous man.

Father Vostrikov dreamed of owning a candle factory. Tormented by the vision of large factory drums winding thick wax ropes, Father Fyodor invented various projects whose implementation was supposed to provide him with basic and working capital to buy the small factory he had long had his eye on in Samara.

Ideas would strike Father Fyodor unexpectedly, and he would immediately set to work. Father Fyodor began to boil marbled laundry soap; he boiled pounds of it, but the soap, although it contained a huge percentage of fats, didn’t lather and, in addition, cost three times more than the “Plow-and-Hammer” brand. The soap then lay soaking and decomposing in the hallway for a long time, so much so that Katerina Alexandrovna would even weep when she walked past it. And then, later, the soap was thrown into the cesspool.

After reading in some livestock magazine that rabbit meat was tender, like chicken, that they bred in large numbers, and that their breeding could bring considerable profits to a thrifty owner, Father Fyodor immediately acquired half a dozen breeders, and two months later, the dog Nerka, frightened by the incredible number of long-eared creatures filling the yard and house, ran away to parts unknown. The accursed townspeople of N turned out to be extremely conservative and with rare unanimity did not buy Vostrikov’s rabbits. Then Father Fyodor, after consulting with his wife, decided to adorn his menu with rabbits, whose meat supposedly surpassed chicken in taste. They prepared roasted rabbits, cutlets, Pozharsky cutlets; rabbits were boiled in soup, served cold for dinner, and baked in babkas. This led to nothing. Father Fyodor calculated that by switching exclusively to a rabbit diet, the family could eat no more than forty animals a month, while the monthly litter was ninety, and this number would increase geometrically each month.

Then the Vostrikovs decided to offer home-cooked meals. Father Fyodor spent the entire evening writing with a chemical pencil on neatly cut sheets of arithmetic paper an advertisement for delicious home-cooked meals, prepared exclusively with fresh cow’s butter. The advertisement began with the words: “Cheap and tasty.” His wife filled an enamel bowl with flour paste, and Father Fyodor, late in the evening, pasted the advertisements on all telegraph poles and near Soviet institutions.

The new venture was a great success. On the very first day, seven people appeared, including Bendin, the military commissariat clerk, and Kozlov, the head of the landscaping sub-department, through whose efforts the town’s only ancient monument — the Triumphal Arch of Elizabeth’s time, which, he claimed, obstructed street traffic — had recently been demolished. They all greatly enjoyed the meal. The next day, fourteen people appeared. They couldn’t skin the rabbits fast enough. For a whole week, business went splendidly, and Father Fyodor was already considering opening a small furrier business, without a motor, when a completely unforeseen incident occurred.

The “Plow and Hammer” cooperative, which had been locked for three weeks due to an inventory count, reopened, and the counter workers, puffing with effort, rolled a barrel of rotten cabbage into the backyard, which was shared with Father Fyodor’s yard, and dumped it into the cesspool. Attracted by the pungent smell, the rabbits flocked to the pit, and the very next morning a plague began among the tender rodents. It raged for only three hours but laid low two hundred and forty breeders and an uncounted number of offspring.

A stunned Father Fyodor quieted down for a full two months and only now, returning from Vorobyaninov’s house and, to his wife’s surprise, locking himself in the bedroom, did his spirits revive. Everything indicated that Father Fyodor was enlightened by a new idea that had seized his entire soul.

Katerina Alexandrovna knocked on the bedroom door with the bone of a bent finger. There was no answer, only the singing intensified. A minute later, the door slightly opened, and Father Fyodor’s face appeared in the crack, a girlish blush playing on it.

“Give me the scissors quickly, mother,” Father Fyodor said rapidly.

“What about supper?”

“Alright. Later.”

Father Fyodor snatched the scissors, locked himself in again, and approached the wall mirror in its scratched black frame.

Next to the mirror hung an old folk print, “The Mirror of the Sinner,” printed from a copper plate and pleasantly hand-colored. “The Mirror of the Sinner” had especially comforted Father Fyodor after the rabbit failure. The popular print clearly showed the transience of all earthly things. Along its top row were four drawings, signed in Slavic script, significant and soul-calming: “This one prays, Ham sows wheat, Japheth holds power. Death rules all.” Death held a scythe and an hourglass with wings. She seemed made of prosthetics and orthopedic parts and stood, legs wide apart, on an empty, hilly ground. Her appearance clearly stated that the rabbit failure was a trivial matter.

Now Father Fyodor liked the picture “Japheth holds power” more. A portly, wealthy man with a beard sat on a throne in a small hall.

Father Fyodor smiled and, looking carefully at himself in the mirror, began to trim his venerable beard. Hair fell to the floor, the scissors squeaked, and five minutes later Father Fyodor realized that he was completely inept at trimming a beard. His beard turned out to be lopsided, indecent, and even suspicious.

After lingering by the mirror a little longer, Father Fyodor grew angry, called his wife, and, holding out the scissors to her, said irritably:

“At least help me, mother. I simply cannot manage my hair.” Matushka was so surprised that she even drew her hands back.

“What have you done to yourself?” she finally uttered.

“Done nothing. Just trimming. Please help. It seems a bit crooked here…”

“Lord,” Matushka said, reaching for Father Fyodor’s curls, “surely, Fedyenka, you aren’t going to join the Renovated Church?”

Father Fyodor was pleased with this turn in the conversation.

“And why, mother, shouldn’t I join the Renovated Church? Are the Renovated not people?”

“People, of course they are people,” Matushka agreed venomously, “they go to movie theaters, they pay alimony…”

“Well, I’ll go running to movie theaters too.”

“Go ahead and run.”

“And I will run.”

“You’ll run yourself ragged. Look at yourself in the mirror.” And indeed, a lively, black-eyed face with a small, wild beard and ridiculously long mustache peered back at Father Fyodor from the mirror.

They began to trim his mustache, bringing it to proportional dimensions.

What followed amazed Matushka even more. Father Fyodor declared that he had to leave that very evening on business and demanded that Katerina Alexandrovna run to her brother the baker and borrow his sheepskin-collared coat and brown duck cap for a week.

“I won’t go anywhere!” Matushka declared and burst into tears.

For half an hour, Father Fyodor paced the room and, frightening his wife with his changed face, talked nonsense. Matushka understood only one thing: Father Fyodor had, for no reason, cut his hair, wanted to go God knows where in a ridiculous cap, and was abandoning her.

“I’m not abandoning you,” Father Fyodor insisted, “I’m not abandoning you, I’ll be back in a week. A man can have business, can’t he? Can he or can’t he?”

“He cannot,” his wife said. Father Fyodor, a gentle man in his dealings with others, even had to thump the table with his fist. Although he thumped cautiously and awkwardly, as he had never done so before, his wife was still very frightened and, putting on her scarf, ran to her brother for civilian clothes.

Left alone, Father Fyodor thought for a moment, said, “It’s hard for women too,” and pulled out a tin-covered chest from under the bed. Such chests are mostly found among Red Army soldiers. They are pasted with striped wallpaper, over which proudly stands a portrait of Budyonny or a cardboard cut-out from a “Plage” cigarette box with three beauties lying on a pebble-strewn Batum shore. The Vostrikovs’ chest, to Father Fyodor’s displeasure, was also pasted with pictures, but there was no Budyonny, nor Batum beauties there. His wife had covered the entire interior of the chest with photographs cut from the magazine “Chronicle of the 1914 War.” There was “The Capture of Przemysl,” and “Distribution of warm clothing to lower ranks in positions,” and who knows what else was there.

Placing the books that lay on top on the floor — a complete set of the magazine “Russian Pilgrim” for 1903, the very thick “History of the Schism,” and a brochure “Russian in Italy,” whose cover showed a smoking Vesuvius — Father Fyodor plunged his hand to the very bottom of the chest and pulled out an old, worn-out bonnet of his wife’s.

Squeezing his eyes shut from the smell of naphthalene that suddenly wafted from the chest, Father Fyodor, tearing the lace and insertions, took a heavy linen sausage from the bonnet. The sausage contained twenty gold ten-ruble coins — all that remained of Father Fyodor’s commercial adventures.

With a habitual movement of his hand, he lifted a corner of his cassock and slipped the sausage into the pocket of his striped trousers. Then he went to the dresser and took fifty rubles in three-ruble and five-ruble notes from a candy box. Twenty rubles still remained in the box.

“That will be enough for household expenses,” he decided.

Chapter 4. The Muse of Distant Wanderings

An hour before the evening mail train arrived, Father Fyodor, in a short coat reaching just below his knees and with a wicker basket, stood in line at the ticket counter, glancing nervously at the entrance doors. He was afraid that his wife, against his explicit wishes, would rush to the station to see him off, and then Prusis, the stallholder, who was sitting in the buffet treating the financial agent to beer, would immediately recognize him. Father Fyodor looked with surprise and shame at his striped trousers, exposed to the gaze of all laypeople.

Boarding the unreserved train was, as usual, chaotic. Passengers, bent under the weight of enormous bags, scurried from the front of the train to the back and from the back to the front. Father Fyodor, bewildered, ran with everyone else. Like everyone else, he spoke to the conductors in an ingratiating voice, and like everyone else, he feared that the cashier had given him the “wrong” ticket. Only when finally allowed into the carriage did he return to his usual calm and even cheered up.

The locomotive cried out at full voice, and the train started, carrying Father Fyodor into the unknown distance on a mysterious errand that, it seemed, promised great benefits.

A fascinating thing is the right-of-way. An ordinary citizen, stepping into it, feels a certain fussiness and quickly transforms either into a passenger, a consignee, or simply a ticketless vagabond, darkening the lives and professional activities of conductor crews and platform controllers.

From the moment a citizen enters the right-of-way, which they amateurishly call a station or a depot, their life sharply changes. Immediately, “Ermak Timofeyevichs” in white aprons with nickel-plated heart-shaped badges rush up to them and obligingly pick up their luggage. From this moment on, the citizen no longer belongs to themselves. They are a passenger and begin to fulfill all the duties of a passenger. These duties are complex but pleasant.

A passenger eats a lot. Ordinary mortals do not eat at night, but a passenger eats at night too. They eat roasted chicken, which is expensive for them, hard-boiled eggs, which are bad for the stomach, and olives. When the train passes over a switch, numerous teapots clatter on the shelves, and chickens, wrapped in newspaper cones and deprived of legs ruthlessly torn off by passengers, bounce around.

But passengers don’t notice any of this. They tell anecdotes. Regularly, every three minutes, the entire carriage bursts into booming laughter. Then silence falls, and a velvety voice delivers the next anecdote:

“An old Jew is dying. His wife stands there, his children. ‘Is Monya here?’ the Jew asks faintly. ‘Yes.’ ‘Has Aunt Brana arrived?’ ‘She has.’ ‘Where’s Grandma? I don’t see her.’ ‘There she stands.’ ‘And Isaac?’ ‘Isaac’s here.’ ‘And the children?’ ‘All the children are here.’ ‘Then who’s left in the shop?!'”

Instantly, the teapots begin to clatter, and the chickens fly about on the upper shelves, disturbed by the thunderous laughter. But the passengers don’t notice this. Each one carries a cherished anecdote in their heart, trembling, waiting for its turn. A new performer, elbowing neighbors and pleadingly shouting, “Oh, they told me this one!” — manages to grab attention with difficulty and begins:

“A Jew comes home and lies down next to his wife. Suddenly he hears someone scratching under the bed. The Jew puts his hand under the bed and asks: ‘Is that you, Jack?’ And Jack licks his hand and answers: ‘It’s me.'”

Passengers die of laughter, the dark night covers the fields, nimble sparks fly from the locomotive’s chimney, and thin semaphores in glowing green glasses pass by fastidiously, looking over the train.

A fascinating thing is the right-of-way! Long, heavy long-distance trains run to all corners of the country. The road is open everywhere. Everywhere the green light burns — the way is clear. The Polar Express ascends to Murmansk. Bent and hunched over the switch, the “First-K” rushes out of Kursky Station, clearing the way to Tiflis. The Far Eastern courier rounds Lake Baikal, approaching the Pacific Ocean at full speed.

The muse of distant wanderings beckons man. It has already torn Father Fyodor from his quiet district abode and cast him into God knows what province. Even the former marshal of the nobility, now civil registry clerk Ippolit Matveevich Vorobyaninov, is disturbed in his very core and has conceived God knows what. People are carried across the country. One finds a radiant bride ten thousand kilometers from his place of service. Another, in pursuit of treasure, abandons the post and telegraph office and, like a schoolboy, runs to Aldan. And a third just sits at home, lovingly stroking a ripe hernia and reading the works of Count Salias, bought for five kopecks instead of a ruble.

On the second day after the funeral, the arrangements for which Master Bezenchuk had kindly taken upon himself, Ippolit Matveevich went to work and, fulfilling his duties, personally registered the demise of Klavdia Ivanovna Petukhova, fifty-nine years old, a housewife, non-party member, residing in district town N and originally from the nobility of Stargorod province. Then Ippolit Matveevich requested his legally permitted two-week leave, received forty-one rubles in holiday pay, and, bidding farewell to his colleagues, went home. On the way, he stopped at the pharmacy.

Pharmacist Leopold Grigorievich, whom his family and friends called Lipa, stood behind the red lacquered counter, surrounded by milky jars of poison, and nervously sold the fire chief’s sister-in-law “Ango cream, against sunburn and freckles, gives exceptional whiteness to the skin.” The fire chief’s sister-in-law, however, demanded “Rachel powder in golden color, gives the body an even, naturally unattainable tan.” But the pharmacy only had Ango cream against sunburn, and the battle of such opposing perfumery products lasted half an hour. Lipa ultimately won, selling the fire chief’s sister-in-law lipstick and a bedbug-boiler, an appliance built on the principle of a samovar but resembling a watering can.

“What did you want?”

“A hair product.”

“For growth, removal, coloring?”

“Growth? What growth!” Ippolit Matveevich said. “For coloring.”

“For coloring, there’s a wonderful product called ‘Titanic.’ Received from customs. Contraband goods. Cannot be washed off with cold or hot water, soap lather, or kerosene. Radical black color. A bottle lasts six months and costs three rubles twelve kopecks. I recommend it as to a good acquaintance.” Ippolit Matveevich twirled the square bottle of “Titanic” in his hands, sighed as he looked at the label, and put the money on the counter.

Ippolit Matveevich returned home and with disgust began to pour “Titanic” on his head and mustache. A foul odor spread through the apartment.

After dinner, the stench lessened, his mustache dried, matted together, and could only be combed with great difficulty. The radical black color turned out to have a somewhat greenish tint, but there was no time to dye it again.

Ippolit Matveevich took the list of valuables he had found the day before from his mother-in-law’s casket, counted all his available money, locked the apartment, put the keys in his back pocket, got on accelerated train No. 7, and left for Stargorod.

Chapter 5. The Great Schemer

At half past eleven, a young man of about twenty-eight entered Stargorod from the northwest, from the direction of the village of Chmarovka. A homeless boy ran behind him.

“Uncle,” he cried cheerfully, “give me ten kopecks!” The young man took a warm apple from his pocket and gave it to the homeless boy, but he wouldn’t give up. Then the pedestrian stopped, looked at the boy ironically, and quietly said:

“Perhaps you’d also like the key to the apartment where the money is kept?”

The presumptuous homeless boy understood the groundlessness of his claims and fell behind.

The young man had lied: he had no money, no apartment where it could be kept, and no key to unlock such an apartment. He didn’t even have a coat. The young man entered the city in a fitted green suit. His powerful neck was wrapped several times in an old wool scarf, and his feet were clad in patent leather boots with orange suede uppers. He wore no socks under his boots. In his hand, the young man held an astrolabe. “O bayadere, ti-ri-rim, ti-ri-ra!” he sang, approaching the market.

Here, he found plenty to do. He squeezed into the line of vendors selling goods from a makeshift stall, held out the astrolabe, and began to shout in a serious voice:

“Who wants an astrolabe? Astrolabe for sale, cheap! Discounts for delegations and women’s departments!”

The unexpected offer did not generate demand for a long time. Delegations of housewives were more interested in scarce goods and crowded around the fabric stalls. The agent of the Stargubrozysk (Stargorod Province Criminal Investigation Department) had already passed the astrolabe vendor twice. But since the astrolabe in no way resembled the typewriter stolen yesterday from the Maslotsentr (Butter Center) office, the agent stopped magnetizing the young man with his eyes and left.

By lunchtime, the astrolabe was sold to a locksmith for three rubles.

“It measures itself,” the young man said, handing the astrolabe to the buyer, “if only there were something to measure.”

Freed from the clever instrument, the cheerful young man had lunch at the “Corner of Taste” canteen and went to explore the city. He walked along Sovetskaya Street, came out onto Krasnoarmeyskaya (formerly Big Pushkinskaya), crossed Kooperativnaya, and found himself back on Sovetskaya. But this was not the same Sovetskaya he had just walked: there were two Sovetskaya streets in the city. After marveling at this circumstance for a while, the young man found himself on Lenskikh Sobytiy Street (formerly Denisovskaya). Near the beautiful two-story mansion No. 28, with a sign that read:

USSR, RSFSR 2nd HOUSE OF SOCIAL SECURITY OF STARGUBSTRAKH

The young man stopped to light a cigarette from the janitor, who was sitting on a stone bench by the gates.

“Hey, old man,” the young man asked, taking a drag, “are there any brides in your town?”

The old janitor wasn’t at all surprised.

“Even a mare can be a bride to someone,” he replied, readily joining the conversation.

“I have no more questions,” the young man quickly stated. And immediately asked a new one:

“In such a house and no brides?”

“Our brides,” the janitor countered, “have long been sought in the afterlife with lanterns. We have a state almshouse here: old women live on full pension.”

“I see. The ones born before historical materialism?”

“That’s right. When they were born, they were born.”

“And what was in this house before historical materialism?”

“When was that?”

“Back then, under the old regime.”

“Ah, under the old regime, my master lived here.”

“A bourgeois?”

“You’re the bourgeois! I told you — a marshal of the nobility.”

“A proletarian, then?”

“You’re the proletarian! I told you — a marshal.”

The conversation with the clever janitor, who had a poor grasp of society’s class structure, would have gone on for God knows how long if the young man hadn’t taken decisive action.

“Listen, grandpa,” he said, “a glass of wine wouldn’t be bad.”

“Well, treat me.”

For an hour, both disappeared, and when they returned, the janitor was already the young man’s most loyal friend.

“So I’ll stay the night with you,” the new friend said.

“As far as I’m concerned, you can live here your whole life, if you’re a good person.”

Having achieved his goal so quickly, the guest promptly descended into the janitor’s room, took off his orange boots, and stretched out on the bench, pondering his plan for tomorrow.

The young man’s name was Ostap Bender. From his biography, he usually only shared one detail: “My father,” he would say, “was a Turkish subject.” The son of a Turkish subject had changed many occupations in his life. The liveliness of his character, which prevented him from dedicating himself to any one pursuit, constantly threw him to different parts of the country and now brought him to Stargorod without socks, without a key, without an apartment, and without money.

Lying in the warmly odorous janitor’s room, Ostap Bender polished in his mind two possible career options.

He could become a bigamist and calmly move from town to town, dragging a new suitcase filled with valuables seized from the current wife.

Or he could go to the Stardetkomissiya (Stargorod Children’s Commission) tomorrow and offer them to take on the distribution of a yet-to-be-painted but brilliantly conceived painting: “Bolsheviks Writing a Letter to Chamberlain,” based on Repin’s popular painting: “Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed IV.” If successful, this option could bring in about four hundred rubles.

Both options were conceived by Ostap during his last stay in Moscow. The bigamy option was born under the influence of a court report he had read in an evening newspaper, which clearly stated that a certain bigamist had received only two years without strict isolation. Option No. 2 was born in Bender’s head when he surveyed the exhibition of AKHRR. (AKHRR – Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia.)

However, both projects had their drawbacks. Starting a career as a bigamist without a magnificent, dappled grey suit was impossible. Moreover, he needed at least ten rubles for representation and seduction. He could, of course, marry in his campaign-green suit, because Bender’s masculine strength and beauty were completely irresistible to provincial Margaritas of marrying age, but that would be, as Ostap put it, “low quality, not clean work.” With the painting, too, not everything was smooth: purely technical difficulties might arise. Would it be convenient to paint Comrade Kalinin in a papakha and white burka, and Comrade Chicherin shirtless? If necessary, of course, all characters could be drawn in ordinary suits, but that wouldn’t be the same.

“It won’t have the same effect!” Ostap said aloud.

Then he noticed that the janitor had been talking passionately about something for a long time. It turned out the janitor was reminiscing about the former owner of the house:

“The police chief saluted him… You come to him, say, on New Year’s with congratulations — he gives you three rubles… On Easter, say, another three rubles. And then, say, on their saint’s day you congratulate him… Well, just from congratulations alone, fifteen rubles would accrue in a year… He even promised to present me with a medal. ‘I want,’ he said, ‘my janitor to have a medal.’ He even said, ‘You, Tikhon, consider yourself already with a medal…'”

“So, did they give it?”

“Just wait… ‘I don’t need a janitor without a medal,’ he said. He went to Saint Petersburg for the medal. Well, the first time, I’ll tell you, it didn’t work out. The gentlemen officials didn’t want to. ‘The Tsar,’ he said, ‘has gone abroad, it’s impossible now.’ The master ordered me to wait. ‘You, Tikhon,’ he said, ‘wait, you won’t be without a medal.'”

“And your master, was he, like, shot?” Ostap asked unexpectedly.

“No one shot him. He left himself. Why would he sit here with the soldiers… And now do they give medals for janitorial service?”

“They do. I can get one for you.” The janitor looked at Bender with respect.

“I can’t be without a medal. It’s my duty.”

“Where did your master go?”

“Who knows! People said he went to Paris.”

“Ah!… White acacia, flowers of emigration… So he’s an emigrant?”

“You’re the emigrant… To Paris, people say, he went. And the house was taken for old women… You can congratulate them every day — you won’t even get a dime!… Ah! What a master he was!…”

At that moment, the rusty bell above the door jiggled. The janitor, grunting, shuffled to the door, opened it, and stepped back in extreme confusion.

On the top step stood Ippolit Matveevich Vorobyaninov, black-mustached and black-haired. His eyes shone under his pince-nez with a pre-war gleam.

“Master!” Tikhon mooed passionately. “From Paris!”

Ippolit Matveevich, embarrassed by the presence of a stranger in the janitor’s room, whose bare purple feet he had only just seen from behind the edge of the table, became flustered and was about to flee, but Ostap Bender quickly sprang up and bowed low before Ippolit Matveevich.

“Though we’re not Paris, you’re welcome to our humble abode.”

“Hello, Tikhon,” Ippolit Matveevich was forced to say, “I’m not from Paris at all. What put that idea in your head?”

But Ostap Bender, whose long, noble nose clearly detected the smell of something cooking, didn’t let the janitor utter a sound.

“Excellent,” he said, winking, “you’re not from Paris. Of course, you’ve come from Kologriv to visit your deceased grandmother.”

As he spoke, he gently embraced the bewildered janitor and ushered him out the door before the latter understood what had happened. When he recovered, he could only grasp that the master had arrived from Paris, that he, Tikhon, had been thrown out of the janitor’s room, and that a paper ruble was clutched in his left hand.

Carefully locking the door behind the janitor, Bender turned to Vorobyaninov, who was still standing in the middle of the room, and said:

“Calm down, everything’s fine. My name is Bender! Perhaps you’ve heard of me?”

“Never heard of you,” Ippolit Matveevich replied nervously.

“Well, how could the name Ostap Bender be known in Paris? Is it warm in Paris now? It’s a good city. My cousin is married there. She recently sent me a silk scarf in a registered letter…”

“What nonsense!” Ippolit Matveevich exclaimed. “What scarves? I didn’t come from Paris, but from…”

“Strange, strange! From Morshansk.” Ippolit Matveevich had never dealt with such a temperamental young man as Bender and felt unwell.

“Well, you know, I’m leaving,” he said.

“Where will you go? You have nowhere to rush. The GPU will come to you themselves.”

Ippolit Matveevich was at a loss for words, unbuttoned his coat with its shedding velvet collar, and sat on the bench, looking unfriendly at Bender.

“I don’t understand you,” he said in a fallen voice.

“That’s not scary. You’ll understand now. Just a moment.”

Ostap put on his orange boots on his bare feet, walked around the room, and began:

“Which border did you cross? Polish? Finnish? Romanian? Must have been an expensive pleasure. An acquaintance of mine recently crossed the border; he lives in Slavuta, on our side, and his wife’s parents are on the other side. He quarreled with his wife over a family matter, and she’s from a touchy family. She spat in his face and ran across the border to her parents. This acquaintance sat alone for three days and saw that things were bad: no dinner, the room was dirty, and he decided to make up. He went out at night and walked across the border to his father-in-law. That’s when the border guards caught him, fabricated a case, imprisoned him for six months, and then expelled him from the trade union. Now, they say, his wife ran back, the fool, and the husband is sitting in prison. She brings him food parcels… And you, did you also cross the Polish border?”

“Honestly,” Ippolit Matveevich stammered, feeling an unexpected dependence on the talkative young man who stood in his way to the diamonds, “honestly, I am a citizen of the RSFSR. After all, I can show my passport…”

“With the modern development of printing in the West, printing a Soviet passport is such a trifle that it’s ridiculous to talk about… An acquaintance of mine even went so far as to print dollars. And you know how hard it is to counterfeit American dollars? The paper has those, you know, multicolored fibers. It requires great technical knowledge. He successfully offloaded them on the Moscow black market; then it turned out that his grandfather, a famous currency speculator, bought them in Kyiv and was completely ruined because the dollars were still fake. So you can also lose out with your passport.”

Ippolit Matveevich, angered that instead of energetically searching for diamonds, he was sitting in a smelly janitor’s room listening to the chatter of a young boor about his acquaintances’ shady dealings, still couldn’t bring himself to leave. He felt a strong timidity at the thought that the unknown young man would blab throughout the city that the former marshal had arrived. Then — everything would be over, and he might even be arrested.

“Please, don’t tell anyone you saw me,” Ippolit Matveevich pleaded, “they might really think I’m an emigrant.”

“There! There! This is congenial! First, the assets: we have an emigrant who has returned to his hometown. Liabilities: he’s afraid of being taken to the GPU.”

“But I’ve told you a thousand times that I’m not an emigrant.”

“Then who are you? Why did you come here?”

“Well, I came from town N on business.”

“What business?”

“Well, personal business.”

“And after that, you say you’re not an emigrant?… An acquaintance of mine also came…”

Here Ippolit Matveevich, driven to despair by Bender’s stories about his acquaintances and seeing that he couldn’t be swayed from his position, surrendered.

“Alright,” he said, “I’ll explain everything to you.” “After all, it’s hard without an assistant,” Ippolit Matveevich thought, “and he seems to be a big crook. Such a person could be useful.”

Chapter 6. Diamond Smoke

Ippolit Matveevich took off his mottled beaver hat, combed his mustache, from which a friendly flock of electric sparks flew out at the touch of the comb, and, clearing his throat decisively, told Ostap Bender, the first scoundrel he encountered, everything he knew about the diamonds from his dying mother-in-law’s words.

During the story, Ostap jumped up several times and, turning to the iron stove, enthusiastically cried out:

“The ice has broken, gentlemen of the jury! The ice has broken!”

An hour later, they were both sitting at a wobbly table, leaning their heads together, reading a long list of jewels that had once adorned his mother-in-law’s fingers, neck, ears, chest, and hair.

Ippolit Matveevich, constantly adjusting the pince-nez that swayed on his nose, emphatically pronounced:

“Three strings of pearls… I remember well. Two with forty beads each, and one large one with a hundred and ten. A diamond pendant… Klavdia Ivanovna said it was worth four thousand, antique work…”

Next came rings: not wedding rings, thick, foolish, and cheap, but thin, light, with clean, washed diamonds inlaid in them; heavy, dazzling pendants, casting multicolored fire onto a small female ear; bracelets in the shape of snakes with emerald scales; a fermoir that consumed the harvest from five hundred dessiatines; a pearl necklace that only a famous operetta prima donna could afford; crowning it all was a forty-thousand-ruble tiara.

Ippolit Matveevich looked around. In the dark corners of the plague-ridden janitor’s room, an emerald spring light flashed and trembled. Diamond smoke hung under the ceiling. Pearl beads rolled across the table and bounced on the floor. The precious mirage shook the room.

An agitated Ippolit Matveevich only came to his senses at the sound of Ostap’s voice.

“Not a bad selection. The stones, I see, were chosen with taste. How much did all this music cost?”

“Seventy to seventy-five thousand.”

“Mhm… So now it’s worth a hundred and fifty thousand.”

“Really that much?” Vorobyaninov asked joyfully.

“No less. Only you, my dear comrade from Paris, should spit on all this.”

“How spit?”

“With saliva,” Ostap replied, “as people spat before the era of historical materialism. Nothing will come of it.”

“How so?”

“Like this. How many chairs were there?”

“A dozen. A drawing-room suite.”

“Your drawing-room suite has probably long since burned in stoves.”

Vorobyaninov was so frightened that he even stood up.

“Calm down, calm down. I’m taking charge of this. The meeting continues, ladies and gentlemen of the jury. By the way, we need to conclude a small agreement, you and I.”

Ippolit Matveevich, breathing heavily, nodded his assent. Then Ostap Bender began to draw up the terms.

“In case the treasure is realized, I, as a direct participant in the concession and technical manager of the operation, receive sixty percent, and you don’t have to pay social insurance for me. I don’t care about that.” Ippolit Matveevich turned pale.

“This is robbery in broad daylight.”

“And how much did you intend to offer me?”

“W-w-well, five percent, well, ten, at most. You understand, that’s fifteen thousand rubles!”

“You don’t want anything else?”

“N-no.”

“Or perhaps you want me to work for free and even give you the key to the apartment where the money is kept?”

“In that case, excuse me,” Vorobyaninov said nasally. “I have every reason to believe that I can handle this myself.”

“Aha! In that case, excuse me,” the magnificent Ostap countered, “I have no less reason, as Andy Tucker used to say, to assume that I can handle your business alone.”

“Swindler!” Ippolit Matveevich cried, trembling. Ostap was cold.

“Listen, mister from Paris, do you know that your diamonds are almost in my pocket! And you only interest me inasmuch as I want to secure your old age.”

Only then did Ippolit Matveevich understand what iron claws had gripped his throat.

“Twenty percent,” he said grimly.

“And my board?” Ostap asked mockingly.

“Twenty-five.”

“And the key to the apartment?”

“But that’s thirty-seven and a half thousand!”

“Why such precision? Well, so be it — fifty percent. Half yours, half mine.”

The bargaining continued. Ostap conceded more. Out of respect for Vorobyaninov’s person, he agreed to work for forty percent.

“Sixty thousand!” Vorobyaninov cried.

“You are quite a vulgar person,” Bender countered, “you love money more than you should.”

“And you don’t love money?” Ippolit Matveevich wailed in a flute-like voice.

“I don’t.”

“Then why do you want sixty thousand?”

“On principle!”

Ippolit Matveevich just caught his breath.

“Well, has the ice broken?” Ostap pressed.

Vorobyaninov puffed and said submissively:

“It has broken.”

“Well, shake on it, district chief of the Comanches! The ice has broken! The ice has broken, gentlemen of the jury!”

After Ippolit Matveevich, offended by the nickname “chief of the Comanches,” demanded an apology and Ostap, delivering an apologetic speech, called him a field marshal, they proceeded to formulate the disposition.

At midnight, the janitor Tikhon, clutching at every passing picket fence and clinging to posts for long stretches, dragged himself to his basement. To his misfortune, it was a new moon.

“Ah! Proletarian of intellectual labor! Worker of the broom!” Ostap exclaimed, seeing the janitor bent over like a wheel.

The janitor mooed in a low and passionate voice, like a toilet sometimes suddenly begins to gurgle hotly and fussily in the dead of night.

“This is congenial,” Ostap informed Ippolit Matveevich, “and your janitor is quite a boor. How can one get so drunk on a single ruble?”

“P-possibly,” the janitor said unexpectedly.

“Listen, Tikhon,” Ippolit Matveevich began, “do you know, my friend, what happened to my furniture?”

Ostap carefully supported Tikhon so that speech could flow freely from his wide-open mouth. Ippolit Matveevich waited in suspense. But from the janitor’s mouth, where teeth grew unevenly, a deafening cry burst forth:

“There w-w-were happy days…”

The janitor’s room filled with thunder and ringing. The janitor diligently and zealously performed the song, not missing a single word. He roared, moving around the room, sometimes unconsciously diving under the table, sometimes hitting his cap against the copper cylindrical weight of a “grandfather clock,” sometimes falling to one knee. He was terribly cheerful.

Ippolit Matveevich was completely lost.

“We’ll have to postpone the interrogation of witnesses until morning,” Ostap said. “Let’s sleep.”

The janitor, heavy in sleep like a dresser, was carried to the bench.

Vorobyaninov and Ostap decided to lie together on the janitor’s bed. Ostap had a black and red plaid “cowboy” shirt under his jacket. There was nothing else under the cowboy shirt. However, Ippolit Matveevich, under the moonlit waistcoat familiar to the reader, had another one — a bright blue worsted one.

“A waistcoat perfect for sale,” Bender said enviously, “it would fit me just right. Sell it.”

Ippolit Matveevich felt awkward refusing his new companion and direct participant in the concession. He, wincing, agreed to sell the waistcoat for his price — eight rubles.

“Money — after the realization of our treasure,” Bender declared, taking the still warm waistcoat from Vorobyaninov.

“No, I can’t do that,” Ippolit Matveevich said, blushing. “Allow me the waistcoat back.”

Ostap’s delicate nature was outraged.

“But this is shopkeeping!” he cried. “To start a hundred-and-fifty-thousand-ruble venture and quarrel over eight rubles! Learn to live lavishly!”

Ippolit Matveevich blushed even more, took out a small notepad, and calligraphically wrote:

25/IV-27

Issued to Comrade Bender

- — 8

Ostap looked into the notebook.

“Oh! If you’re already opening an account for me, at least keep it correctly. Set up a debit, set up a credit. Don’t forget to enter the sixty thousand rubles you owe me in the debit, and the waistcoat in the credit. The balance in my favor is fifty-nine thousand nine hundred ninety-two rubles. Still survivable.”

After this, Ostap fell into a soundless, childlike sleep. And Ippolit Matveevich took off his woolen wristbands and baronial boots, and, remaining in his patched hunting underwear, snorting, he crawled under the blanket. He was very uncomfortable. On the outer side, where the blanket was lacking, it was cold, and on the other side, he was burning from the young, idea-filled body of the great schemer. All three had dreams.

Vorobyaninov had dark dreams: microbes, the criminal investigation department, velvet Tolstoy blouses, and the coffin maker Bezenchuk in a tuxedo, but unshaven.

Ostap saw Mount Fuji-Yama, the head of the Butter Trust, and Taras Bulba selling postcards with views of Dneprostroy.

And the janitor dreamed that a horse had left the stable. In his dream, he searched for it until morning and, not finding it, woke up broken and gloomy. For a long time, he looked with surprise at the people sleeping in his bed. Understanding nothing, he took his broom and headed for the street to perform his direct duties: picking up horse droppings and shouting at the almshouse residents.

Chapter 7. The Traces of “Titanic”

Ippolit Matveevich woke up as usual at half past seven, rumbled “gut morgen,” and headed to the washbasin. He washed with pleasure: spitting, lamenting, and shaking his head to get rid of the water that had gotten into his ears. Drying himself was pleasant, but when he took the towel from his face, Ippolit Matveevich saw that it was stained with the radical black color that had been dyeing his horizontal mustache since the day before yesterday. Ippolit Matveevich’s heart sank. He rushed to his pocket mirror. The mirror reflected a large nose and a left mustache as green as young grass. Ippolit Matveevich quickly moved the mirror to the right. The right mustache was the same disgusting color. Bending his head, as if wanting to butt the mirror, the unfortunate man saw that the radical black color still dominated the center of his hair, but the edges were bordered by the same grassy fringe.

Ippolit Matveevich’s entire being let out such a loud groan that Ostap Bender opened his eyes.

“You’re out of your mind!” Bender exclaimed and immediately closed his sleepy eyelids.

“Comrade Bender,” the victim of “Titanic” whispered imploringly.

Ostap woke up after many shoves and persuasions. He looked carefully at Ippolit Matveevich and laughed joyfully. Turning away from the founding director of the concession, the chief operations manager and technical director shuddered, grabbed the back of the bed, cried, “I can’t!” — and then burst out laughing again.

“It’s not nice of you, Comrade Bender,” said Ippolit Matveevich, trembling his green mustache.

This gave new strength to the exhausted Ostap. His hearty laughter continued for another ten minutes. Catching his breath, he immediately became very serious.