The Red Laugh, Leonid Andreyev: Read FREE Full Text Online (English Translation)

You can now read the full text for free of one of the most powerful and harrowing literary responses to war and psychological trauma — The Red Laugh by the visionary author Leonid Andreyev. This essential piece of reflective fiction Russian literature is available for online reading here in a high-quality English translation.

Dive into this captivating masterpiece and experience the descent into madness through the fragmented diary entries of a soldier and his brother, a vivid and prophetic depiction of the absurd horrors of modern conflict. Start reading instantly without any download required. This exclusive free access is your gateway to the world of great Russian authors and their works.

You can also buy this book from us in the definitive paperback edition via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

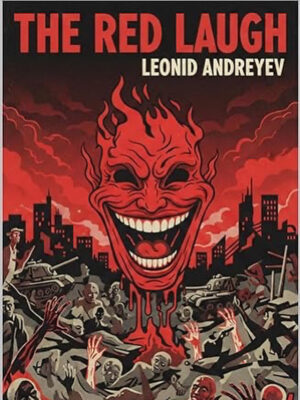

The Red Laugh by Leonid Andreyev

Page Count: 138Year: 1904READ FREEProducts search This is a surreal parable about the insane horrors of war, so powerful that, returning in the crippled souls of men from the fronts, they continue to live, gradually materializing and tormenting, torturing, driving mad other, as yet untouched, victims. “The Red Laugh” is at first glance a strange, incomprehensible story. The horrors […]

€18.00 Login to Wishlist

First published in 1905, “Znanie”

Collection, Book 6, Russian Empire

This book is in the public domain

Reprint by Publishing House №10

Publication date July 17, 2025

Translation from Russian

85 Pages, Font 12 pt, Bookman Old Style

Electronic edition, File size 1.0 MB

Cover design, Translate by Yulia Basharova

Copyright© Yulia Basharova 2025. All rights reserved

Table of Contents

PART ONE

First Excerpt

…madness and horror.

I first felt it when we were marching along some road — we had been marching for ten hours continuously, without stopping, without slowing down, without picking up those who fell, leaving them to the enemy who was moving in solid masses behind us and, three or four hours later, erased the traces of our feet with their own. The heat was stifling. I don’t know how many degrees it was: forty, fifty, or more; I only know that it was continuous, hopelessly even, and profound. The sun was so immense, so fiery and terrifying, as if the earth had drawn closer to it and would soon burn in that merciless fire. And my eyes couldn’t look. My small, narrowed pupil, tiny as a poppy seed, searched in vain for darkness beneath closed eyelids: the sun pierced the thin membrane and entered my tormented brain with a bloody light. But it was still better this way, and for a long time, perhaps several hours, I walked with my eyes closed, hearing the crowd moving around me: the heavy and uneven tramp of feet, human and equine, the grinding of iron wheels crushing small stones, someone’s heavy, strained breathing, and the dry smacking of parched lips. But I heard no words. Everyone was silent, as if an army of mutes was moving, and when someone fell, they fell silently, and others stumbled over their body, fell, silently got up, and, without looking back, walked on — as if these mutes were also deaf and blind. I myself stumbled and fell several times, and then involuntarily opened my eyes — and what I saw seemed like a wild fantasy, a heavy delirium of a maddened earth. The scorching air trembled, and silently, as if ready to flow, the stones trembled; and the distant rows of people at the bend, the guns and horses, detached from the earth and silently, gelatinously swayed — as if these weren’t living people marching, but an army of incorporeal shadows. The enormous, close, terrifying sun ignited thousands of small dazzling suns on every rifle barrel, on every metal plate, and they crept into my eyes from everywhere, from the sides and below, fiery white, sharp as the tips of white-hot bayonets. And the desiccating, scorching heat penetrated to the very depths of my body, into my bones, into my brain, and sometimes it seemed as if not a head was swaying on my shoulders, but some strange and unusual sphere, heavy and light, alien and terrifying.

And then — and then suddenly I remembered home: a corner of a room, a scrap of blue wallpaper, and a dusty, untouched water carafe on my table — on my table, which had one leg shorter than the other two, with a folded piece of paper tucked underneath it. And in the next room, though I couldn’t see them, my wife and son were supposedly there. If I could have screamed, I would have — so extraordinary was this simple and peaceful image, this scrap of blue wallpaper and the dusty, untouched carafe.

I know I stopped, raising my hands, but someone behind me pushed me; I quickly strode forward, pushing through the crowd, hurrying somewhere, no longer feeling either the heat or the fatigue. And I walked like that for a long time through the endless silent rows, past red, sunburned necks, almost touching the hot, weakly lowered bayonets, when the thought of what I was doing, where I was hurrying to — stopped me. Just as quickly, I turned aside, broke into the open, climbed over some ravine, and sat down anxiously on a stone, as if this rough, hot stone was the goal of all my aspirations.

And then, for the first time, I felt it. I clearly saw that these people, silently marching in the sunlight, numb with fatigue and heat, swaying and falling, that they were mad. They don’t know where they’re going, they don’t know why this sun is here, they know nothing. They don’t have heads on their shoulders, but strange and terrifying spheres. Here’s one, like me, hastily pushing through the ranks and falling; here’s another, a third. Here, a horse’s head rose above the crowd with red, insane eyes and a wide, bared mouth, only hinting at some terrifying and unusual cry, rose, fell, and in that spot for a moment the people thickened, paused, hoarse, muffled voices were heard, a short shot, and then again the silent, endless movement. I’ve been sitting on this stone for an hour now, and they keep passing by me, and the earth still trembles, and the air, and the distant, ghostly rows. The desiccating heat pierces me again, and I no longer remember what appeared to me for a second, but they keep passing by me, passing, and I don’t understand who they are. An hour ago, I was alone on this stone, but now a small group of gray people has gathered around me: some are lying motionless, perhaps dead; others are sitting and staring blankly at those passing by, just like me. Some have rifles, and they look like soldiers; others are almost naked, and their skin is so crimson red that one doesn’t want to look at it. Not far from me, someone is lying naked on his back. From the way he indifferently pressed his face into the sharp and hot stone, from the whiteness of his upturned palm, it’s clear that he’s dead, but his back is red, as if alive, and only a slight yellowish film, like on smoked meat, speaks of death. I want to move away from him, but I have no strength, and, swaying, I look at the endlessly moving, ghostly swaying rows. From the state of my head, I know that I will also have a sunstroke soon, but I await it calmly, as in a dream, where death is only a stage on the path of wondrous and confusing visions.

And I see a soldier detaching himself from the crowd and resolutely heading towards us. For a moment he disappears into the ditch, and when he climbs out and walks again, his steps are unsteady, and something final is felt in his attempts to gather his disintegrating body. He walks so directly at me that through the heavy stupor gripping my brain, I get scared and ask:

“What do you want?”

He stops, as if only waiting for a word, and stands there, huge, bearded, with a torn collar. He has no rifle, his trousers are held by one button, and through the tear, his white body is visible. His arms and legs are splayed, and he evidently tries to gather them, but cannot: he brings his arms together, and they immediately fall apart.

“What’s wrong? You’d better sit down,” I say.

But he stands, unsuccessfully trying to compose himself, silent and looking at me. And I involuntarily rise from the stone and, swaying, look into his eyes — and see in them an abyss of horror and madness. Everyone’s pupils are narrowed — but his are dilated across his whole eye; what a sea of fire he must be seeing through those enormous black windows! Perhaps it seemed to me, perhaps there was only death in his gaze — but no, I’m not mistaken: in those black, bottomless pupils, outlined by a narrow orange circle, like in birds, there was more than death, more than the horror of death.

“Go away!” I shout, backing away. “Go away!”

And as if he was only waiting for a word — he falls on me, knocking me down, still just as huge, sprawling, and voiceless. I shudderingly free my pinned legs, jump up, and want to run — somewhere away from the people, into the sunny, deserted, trembling distance, when to my left, on the summit, a shot booms and immediately after it, like an echo, two more. Somewhere above my head, with joyful, multi-voiced squeals, shouts, and howls, a grenade flies past.

They’ve outflanked us!

There is no more deadly heat, no more of that fear, no fatigue. My thoughts are clear, my perceptions distinct and sharp; when, breathless, I run up to the forming ranks, I see faces that have brightened, as if joyful, I hear hoarse but loud voices, commands, jokes. The sun seemed to climb higher, so as not to interfere, it dimmed, quieted — and again with a joyful squeal, like a witch, a grenade cut through the air.

I approached.

Second Excerpt

…almost all the horses and servants. The same on the eighth battery. On ours, the twelfth, by the end of the third day, only three guns remained — the rest were knocked out — six men serving them, and one officer: myself. For twenty hours we hadn’t slept or eaten anything; for three days, a satanic roar and screech enveloped us in a cloud of madness, separating us from the earth, from the sky, from our own — and we, the living, wandered like sleepwalkers. The dead lay peacefully, while we moved, did our work, spoke, and even laughed, and were like sleepwalkers. Our movements were confident and swift, commands clear, execution precise — but if suddenly asked who he was, each one would hardly find an answer in their darkened mind. As in a dream, all faces seemed long familiar, and everything that happened also seemed long familiar, understandable, something that had already happened; but when I began to peer intently into a face or at a gun, or listen to the roar — everything struck me with its novelty and infinite mystery. Night came imperceptibly, and we barely had time to see it and wonder where it came from before the sun was burning above us again. And only from those who came to the battery did we learn that the battle was entering its third day, and immediately forgot about it: it seemed to us that it was one endless, beginningless day, sometimes dark, sometimes bright, but equally incomprehensible, equally blind. And none of us feared death, for none of us understood what death was.

On the third or fourth night, I don’t remember, I lay down for a minute behind the breastwork, and as soon as I closed my eyes, the same familiar and extraordinary image appeared: a scrap of blue wallpaper and an untouched, dusty carafe on my table. And in the next room — though I couldn’t see them — my wife and son were supposedly there. But only now, a lamp with a green shade was lit on the table, meaning it was evening or night. The image stood still, and for a long time, very calmly, very attentively, I examined how the light played in the crystal of the carafe, looked at the wallpaper, and wondered why my son wasn’t sleeping: it was already night, and it was time for him to sleep. Then I again examined the wallpaper, all those swirls, silvery flowers, some kind of gratings and pipes — I never thought I knew my room so well. Sometimes I opened my eyes and saw a black sky with some beautiful fiery streaks, and then closed them again, and again looked at the wallpaper, the shining carafe, and wondered why my son wasn’t sleeping: it was already night, and he needed to sleep. Once, a grenade exploded not far from me, shaking my legs, and someone cried out loudly, louder than the explosion itself, and I thought: “Someone’s killed!” — but I didn’t get up or take my eyes off the light blue wallpaper and the carafe.

Then I got up, walked around, gave orders, looked at faces, aimed the sights, and kept thinking: why isn’t my son sleeping? Once I asked a driver about it, and he explained something to me at length and in detail, and we both nodded our heads. And he laughed, and his left eyebrow twitched, and his eye cunningly winked at someone behind him. And behind him, only the soles of someone’s feet were visible, nothing else.

By this time, it was already light, and suddenly — rain dropped. Rain — just like ours, the most ordinary droplets of water. It was so unexpected and out of place, and we were all so afraid of getting wet, that we abandoned our guns, stopped shooting, and began to hide wherever we could. The driver I had just spoken with crawled under the gun carriage and dozed there, though he could be crushed any minute; the fat bombardier, for some reason, began undressing a dead man, and I rushed around the battery looking for something — either a cloak or an umbrella. And immediately, across the entire vast space where rain had fallen from the passing cloud, an unusual silence descended. A shrapnel shell belatedly whizzed and exploded, and then it became quiet — so quiet that one could hear the fat bombardier snorting and the raindrops tapping on the stone and the guns. And this quiet, broken tapping, reminiscent of autumn, and the smell of wet earth, and the silence — as if for a moment they tore apart the bloody and wild nightmare, and when I looked at the wet, water-shining gun, it unexpectedly and strangely reminded me of something dear, quiet, perhaps my childhood, or my first love. But in the distance, the first shot rang out especially loudly, and the enchantment of the momentary silence vanished; with the same suddenness with which people had hidden, they began to crawl out from under their covers; the fat bombardier yelled at someone; a gun roared, then a second, and again a bloody, inseparable fog enveloped our tormented minds. And no one noticed when the rain stopped; I only remember that water was rolling off the dead bombardier, off his thick, bloated, yellow face, so the rain probably lasted quite long…

…A young volunteer stood before me, reporting, hand to his cap, that the general was asking us to hold out for just two hours, and then reinforcements would arrive. I was thinking about why my son wasn’t sleeping, and replied that I could hold out indefinitely. But then, for some reason, his face interested me, probably because of its extraordinary and striking paleness. I had never seen anything whiter than this face: even the dead have more color in their faces than this young, beardless man. He must have been terribly frightened on his way to us and couldn’t recover; and he held his hand to his cap to ward off the insane fear with this habitual and simple movement.

“Are you scared?” I asked, touching his elbow. But his elbow was like wood, and he himself smiled quietly and remained silent. More accurately, only his lips twitched in a smile, and in his eyes there was only youth and fear — nothing more. “Are you scared?” I repeated gently.

His lips twitched, trying to utter a word, and at the same instant something incomprehensible, monstrous, supernatural occurred. A warm wind blew on my right cheek, shaking me violently — and that was all, but before my eyes, in place of the pale face, there was something short, blunt, red, and blood poured from it as if from an uncorked bottle, like they’re drawn on bad signs. And in that short, red, flowing thing, some kind of smile still lingered, a toothless laugh — a red laugh.

I recognized it, this red laugh. I sought and found it, this red laugh. Now I understood what was in all these disfigured, torn, strange bodies. It was the red laugh. It’s in the sky, it’s in the sun, and soon it will spread across the whole earth, this red laugh!

And they, clearly and calmly like sleepwalkers…

Third Excerpt

…madness and horror.

They say that many mentally ill people have appeared in both our army and the enemy’s. We’ve already opened four psychiatric wards. When I was at headquarters, the adjutant showed me…

Fourth Excerpt

…coiled like snakes. He saw how the wire, cut from one end, cut through the air and enveloped three soldiers. The barbs tore uniforms, dug into flesh, and the soldiers screamed, whirling frantically, two dragging a third who was already dead. Then only one remained alive, and he was pushing away the two dead men, while they dragged, whirled, tumbled over each other and over him — and then suddenly all became still.

He said that at this one fence, no less than two thousand men perished. While they were cutting the wire and getting entangled in its snake-like coils, they were showered with a continuous rain of bullets and grapeshot. He insists it was very terrifying and that this attack would have ended in a panicked retreat if they had known which direction to flee. But ten or twelve continuous rows of wire and the struggle with it, a whole labyrinth of wolf pits with sharpened stakes at the bottom, so disoriented them that it was absolutely impossible to determine a direction.

Some, as if blind, stumbled into deep, funnel-shaped pits and hung by their bellies on the sharp stakes, twitching and dancing like toy puppets; new bodies pressed down on them, and soon the entire pit was filled to the brim with a writhing mass of bloody living and dead bodies. From everywhere below, hands reached out, their fingers convulsively contracting, grabbing everything, and whoever fell into this trap could not climb back out: hundreds of fingers, strong and blind as claws, squeezed legs, clung to clothing, pulled a man down onto themselves, dug into eyes, and choked. Many, like drunks, ran straight onto the wire, got caught, and began to scream until a bullet finished them.

Generally, everyone seemed like drunks to him: some swore terribly, others roared with laughter when the wire snagged their arm or leg, and then died immediately. He himself, though he hadn’t drunk or eaten anything since morning, felt very strange: his head spun, and fear was momentarily replaced by wild ecstasy — the ecstasy of fear. When someone next to him began to sing, he joined in, and soon a whole, very harmonious chorus formed. He doesn’t remember what they sang, but it was something very cheerful, a dance tune. Yes, they sang — and everything around was red with blood. The sky itself seemed red, and one might have thought that some catastrophe had occurred in the universe, some strange change and disappearance of colors: blue and green and other familiar, quiet colors had vanished, and the sun ignited with a red Bengal light.

“The red laugh,” I said.

But he didn’t understand.

“Yes, and they laughed. I already told you. Like drunks. Maybe they even danced, there was something. At least, the movements of those three resembled a dance.”

He clearly remembers: when he was shot through the chest and fell, for some time, until he lost consciousness, he kept jerking his legs, as if he was dancing along to someone. And now he recalls this attack with a strange feeling: partly with fear, partly as if with a desire to experience the same thing again.

“And another bullet to the chest?” I asked.

“Well, not every time a bullet. But it would be good, comrade, to get a medal for bravery.”

He lay on his back, yellow, sharp-nosed, with prominent cheekbones and sunken eyes — he lay, resembling a dead man, and dreamed of a medal. An abscess had already begun on him, he had a high fever, and in three days he would be thrown into a pit with the dead, but he lay, smiled dreamily, and spoke of a medal.

“Did you send a telegram to your mother?” I asked.

He looked at me with fright, but sternly and maliciously, and didn’t answer. And I fell silent, and the groans and delirious ravings of the wounded became audible. But when I got up to leave, he squeezed my hand with his hot, but still strong hand, and gripped me with his sunken, burning eyes, bewildered and yearning.

“What is this, huh? What is this?” he asked fearfully and insistently, tugging my hand.

“What?”

“Well, generally… all this. She’s waiting for me, isn’t she? I can’t just… Fatherland — how can you explain what ‘fatherland’ is to her?”

“The red laugh,” I replied.

“Ah! You’re always joking, but I’m serious. I need to explain, but how do you explain it to her? If you knew what she writes! What she writes! And you don’t know, her words are — gray. And you…” He looked curiously at my head, poked it with a finger, and, unexpectedly laughing, said: “And you’ve gone bald. Did you notice?”

“There are no mirrors here.”

“There are many gray and bald people here. Listen, give me a mirror. Give it! I feel white hair growing from my head. Give me a mirror!”

He was becoming delirious, he cried and screamed, and I left the infirmary.

That evening we held a celebration — a sad and strange celebration, where the shadows of the dead were among the guests. We decided to gather in the evening and drink tea, like at home, like at a picnic, and we got a samovar, and even a lemon and glasses, and settled under a tree — like at home, like at a picnic. One by one, then two, then three, comrades gathered, approaching noisily, with conversation, with jokes, full of cheerful expectation, but soon fell silent, avoiding looking at each other, for something strange was in this gathering of survivors. Ragged, dirty, scratching themselves as if with a severe itch, overgrown with hair, thin and emaciated, having lost their familiar and accustomed appearance, it was as if only now, around the samovar, we saw each other — saw and were frightened. I searched in vain for familiar faces in this crowd of bewildered people and couldn’t find any. These people, restless, hurried, with jerky movements, flinching at every sound, constantly looking for something behind them, trying to fill that mysterious void they were afraid to look into with excessive gesturing — they were new, alien people whom I didn’t know. And their voices sounded differently, abruptly, in jerks, uttering words with difficulty and easily, for no significant reason, turning into a shout or a senseless, uncontrollable laugh. And everything was alien. The tree was alien, and the sunset alien, and the water alien, with a peculiar smell and taste, as if with the dead, we had left the earth and moved into some other world — a world of mysterious phenomena and ominous, gloomy shadows. The sunset was yellow, cold; above it, heavy, black, unlit, motionless clouds hung, and the earth beneath it was black, and our faces in this ominous light were yellow, like the faces of the dead. We all looked at the samovar, and it had gone out, reflecting the yellowness and menace of the sunset on its sides, and also became alien, dead, and incomprehensible.

“Where are we?” someone asked, and in his voice there was anxiety and fear.

Someone sighed. Someone convulsively cracked their fingers, someone laughed, someone jumped up and began to walk quickly around the table. Now one could often encounter these fast-pacing, almost running people, sometimes strangely silent, sometimes strangely muttering something.

“At war,” replied the one who was laughing, and again burst into a muffled, prolonged laugh, as if choking on something.

“Why is he laughing?” someone indignantly cried. “Listen, stop it!”

He choked again, chuckled, and obediently fell silent. It was getting dark, the cloud was pressing down on the earth, and we could barely distinguish each other’s yellow, ghostly faces. Someone asked:

“And where’s Botik?”

“Botik” — that’s what we called our comrade, a small officer in large waterproof boots.

“He was just here. Botik, where are you?”

“Botik, don’t hide! We can smell your boots.”

Everyone laughed, and, interrupting the laughter, a rough, indignant voice sounded from the darkness:

“Stop it, how shameful. Botik was killed this morning on reconnaissance.”

“He was just here. That’s a mistake.”

“You imagined it. Hey, by the samovar, quickly cut me some lemon.”

“Me too! Me too!”

“All the lemon is gone.”

“What is this, gentlemen,” a quiet and offended voice sounded with yearning, almost crying. “And I only came for the lemon.”

The other one laughed again, muffled and prolonged, and no one stopped him. But he soon fell silent. Chuckled once more and became quiet. Someone said:

“Tomorrow’s the offensive.”

And several voices irritably cried out:

“Leave it! What offensive!”

“You know yourselves…”

“Leave it. Can’t we talk about something else? What is this!”

The sunset faded. The cloud lifted, and it seemed to grow lighter, and faces became familiar, and the one who was pacing around us calmed down and sat down.

“How are things at home now?” he asked vaguely, and in his voice there was a guilty smile.

And again, everything became terrifying, incomprehensible, and alien — to the point of horror, almost to the point of losing consciousness. And we all immediately started talking, shouting, bustling, moving glasses, touching each other’s shoulders, arms, knees — and then suddenly fell silent, yielding to the incomprehensible.

“Home?” someone shouted from the darkness. His voice was hoarse from excitement, from fear, from anger, and trembled. And some of his words wouldn’t come out, as if he had forgotten how to speak them.

“Home? What home, is there any home anywhere? Don’t interrupt me, or I’ll start shooting. At home I took baths every day — you understand, baths with water, water to the very brim. And now I don’t wash every day, and I have scabs on my head, some kind of scurvy, and my whole body itches, and things crawl on my body, crawl… I’m going crazy from the dirt, and you say — home! I’m like cattle, I despise myself, I don’t recognize myself, and death is not that scary at all. You’re tearing my brain apart with your shrapnel, my brain! No matter where they shoot, it all hits my brain — you say — home. What home? A street, windows, people, and I wouldn’t go out on the street now — I’m ashamed. You brought a samovar, and I was ashamed to look at it. At the samovar.”

The other one laughed again. Someone shouted:

“This is hell. I’m going home.”

“You don’t understand what home is!”

“Home? Listen: he wants to go home!”

A general laugh and a terrible cry arose — and again everyone fell silent, yielding to the incomprehensible. And then it wasn’t just me, but all of us, however many there were, felt it. It was coming at us from those dark, mysterious, and alien fields; it was rising from the deep black ravines, where perhaps forgotten people, lost among the stones, were still dying; it was pouring from this alien, unseen sky. Silently, losing consciousness from horror, we stood around the extinguished samovar, and from the sky, a huge, formless shadow, risen above the world, gazed at us intently and silently. Suddenly, very close to us, probably near the regimental commander, music began to play, and madly cheerful, loud sounds seemed to flare up amidst the night and silence. It played with mad cheerfulness and defiance, hurried, discordant, too loud, too cheerful, and it was clear that those who played and those who listened also saw, just as we did, this huge, formless shadow risen above the world.

And the one in the orchestra who played the trumpet, apparently already carried within himself, in his brain, in his ears, this huge silent shadow. The jerky and broken sound darted, and jumped, and ran somewhere away from the others — lonely, trembling with horror, mad. And the other sounds seemed to look back at him; stumbling awkwardly, falling and rising, they ran in a broken crowd, too loud, too cheerful, too close to the black ravines where perhaps forgotten people, lost among the stones, were still dying.

And for a long time we stood around the extinguished samovar and were silent.

Fifth Excerpt

…I was already asleep when the doctor woke me with gentle nudges. I cried out, waking and jumping up, as we all cried out when roused, and rushed to the tent exit. But the doctor held my hand firmly and apologized:

“I scared you, forgive me. And I know you want to sleep…”

“Five days…” I mumbled, drifting off, and fell asleep and slept, it seemed to me, for a long time, when the doctor spoke again, gently nudging my sides and legs.

“But it’s very necessary. My dear fellow, please, it’s so necessary. I keep thinking… I can’t. I keep thinking there are still wounded left there…”

“What wounded? You’ve been transporting them all day. Leave me alone. This isn’t fair, I haven’t slept for five days!”

“My dear fellow, don’t be angry,” the doctor mumbled, clumsily putting a cap on my head. “Everyone’s asleep, I can’t wake anyone. I got a locomotive and seven cars, but we need people. I understand, you see… I myself am afraid to fall asleep. I don’t remember when I slept. I think I’m starting to hallucinate. My dear fellow, put your feet down, just one foot, yes, like that, like that…”

The doctor was pale and swaying, and it was evident that if he just lay down, he would sleep for several days straight. And my legs buckled beneath me, and I’m sure I fell asleep while we were walking — so suddenly and unexpectedly, from nowhere, a row of black silhouettes, a locomotive and cars, appeared before us. Nearby, some people, barely visible in the darkness, roamed slowly and silently. There wasn’t a single lantern on the locomotive or in the cars, and only a reddish, dim light fell onto the tracks from the closed ash pan.

“What’s that?” I asked, stepping back.

“But we’re going. Did you forget? We’re going,” the doctor mumbled.

The night was cold, and he shivered with cold, and looking at him, I felt the same frequent, tickling shiver throughout my body.

“Damn you!” I shouted loudly. “Couldn’t you take someone else…”

“Quiet, please, quiet!” The doctor grabbed my hand.

Someone from the darkness said:

“Now fire a volley from all guns, no one will stir. They’re asleep too. You can go up and bandage all the sleeping ones. I just walked past the sentry himself. He looked at me and said nothing, didn’t move. He’s probably asleep too. And how he doesn’t fall.”

The speaker yawned, and his clothes rustled: he was evidently stretching. I leaned my chest on the edge of the car to climb in — and sleep immediately overcame me. Someone lifted me from behind and laid me down, and for some reason I pushed him away with my feet — and fell asleep again, and as if in a dream, heard snatches of conversation:

“At the seventh verst.”

“Did you forget the lanterns?”

“No, he won’t go.”

“Bring it here. Back up a bit. There.”

The cars jerked in place, something knocked. And gradually, from all these sounds and from the fact that I lay comfortably and calmly, sleep began to leave me. And the doctor fell asleep, and when I took his hand, it was like a dead person’s: limp and heavy. The train was already moving slowly and cautiously, trembling slightly and as if feeling its way. The medical student lit a candle in the lantern, illuminated the walls and the black hole of the doors, and said angrily:

“What the hell! We’re very much needed right now. And you wake him before he’s fully awake. Then you can’t do anything, I know from experience.”

We roused the doctor, and he sat up, looking around bewildered. He wanted to fall back asleep, but we wouldn’t let him.

“A swig of vodka would be good right now,” the student said.

We took a gulp of cognac, and sleep vanished completely. The large, black rectangle of the doors began to turn pink, then red — somewhere beyond the hills, a huge, silent glow appeared, as if the sun was rising in the middle of the night.

“That’s far. About twenty versts away.”

“I’m cold,” the doctor said, teeth chattering.

The student looked out the door and motioned to me with his hand. I looked: in different places on the horizon, in a silent chain, stood the same motionless glows, as if dozens of suns were rising simultaneously. And it was no longer so dark. The distant hills were densely black, clearly outlining a broken and wavy line, and nearby everything was flooded with a quiet, red light, silent and motionless. I looked at the student: his face was colored with the same red, ghostly color of blood, transformed into air and light.

“Many wounded?” I asked.

He waved his hand.

“Many madmen. More than wounded.”

“Real ones?”

“What else?”

He looked at me, and in his eyes was the same stopped, wild look, full of cold horror, as in that soldier who died of sunstroke.

“Stop it,” I said, turning away.

“The doctor’s mad too. Just look at him.”

The doctor didn’t hear. He sat cross-legged, like Turks do, swaying, his lips and fingertips moving silently. And in his gaze was the same fixed, petrified, dully stunned look.

“I’m cold,” he said and smiled.

“To hell with all of you!” I shouted, retreating to a corner of the car. “Why did you call me?”

No one answered. The student gazed at the silent, expanding glow, and his neck with its curly hair was young, and when I looked at it, for some reason, I kept imagining a delicate woman’s hand ruffling that hair. And this image was so unpleasant that I began to hate the student and couldn’t look at him without revulsion.

“How old are you?” I asked, but he didn’t turn or answer.

The doctor swayed.

“I’m cold.”

“When I think,” the student said, without turning, “when I think that somewhere there are streets, houses, a university…”

He broke off, as if he had said everything, and fell silent. The train stopped almost abruptly, making me hit the wall, and voices were heard. We jumped out.

Right in front of the locomotive, on the tracks, lay something, a small lump, from which a leg protruded.

“Wounded?”

“No, dead. Head torn off. But, as you wish, I’ll light the front lantern. Otherwise, we’ll run over something else.”

The lump with the protruding leg was thrown aside; the leg briefly kicked up, as if he wanted to run through the air, and everything disappeared into the black ditch. The lantern lit up, and the locomotive immediately turned black.

“Listen!” someone whispered with quiet horror.

How did we not hear it before! From everywhere — the exact location couldn’t be determined — a steady, scraping moan came, astonishingly calm in its breadth and even seemingly indifferent. We had heard many cries and moans, but this was unlike anything we had heard. On the vague reddish surface, the eye could not discern anything, and so it seemed that the earth itself was moaning, or the sky, illuminated by an unrising sun.

“Fifth verst,” said the engineer.

“It’s from there,” the doctor pointed forward.

The student flinched and slowly turned to us:

“What is this? This can’t be heard!”

“Move!”

We walked on foot in front of the locomotive, and a continuous long shadow stretched from us onto the tracks, and it was not black, but vaguely red from the quiet, motionless light that stood silently in different parts of the black sky. And with each step we took, this wild, unheard-of moan, which had no visible source, ominously grew — as if the red air was moaning, as if the earth and sky were moaning. In its continuity and strange indifference, it sometimes resembled the chirping of crickets in a meadow — the steady and hot chirping of crickets in a summer meadow. And corpses began to appear more and more often. We quickly examined them and threw them off the tracks — these indifferent, calm, limp corpses, leaving dark oily stains of absorbed blood where they lay, and at first we counted them, and then lost count and stopped. There were many of them — too many for this ominous night, breathing cold and moaning with every particle of its being.

“What is this!” the doctor shouted and shook his fist at someone. “You — listen…”

The sixth verst was approaching, and the moans became more definite, sharper, and we could already feel the distorted mouths uttering these voices. We tremblingly peered into the pink haze, deceptive in its ghostly light, when almost beside us, by the tracks, below, someone groaned loudly with an inviting, weeping moan. We immediately found him, this wounded man, whose face was nothing but eyes — so large they seemed when the lantern light fell on his face. He stopped moaning and only alternately shifted his eyes to each of us and to our lanterns, and in his gaze was an insane joy that he saw people and lights, and an insane fear that all this would now disappear like a vision. Perhaps he had already dreamed more than once of people bending over with lanterns and disappearing into a bloody and vague nightmare.

We moved on and almost immediately stumbled upon two wounded men; one lay on the tracks, the other moaned in the ditch. As they were being picked up, the doctor, trembling with anger, said to me:

“Well?” And turned away. A few steps further, we met a lightly wounded man who was walking by himself, supporting one arm with the other. He moved with his head back, directly towards us, and seemed not to notice when we parted, giving him way. It seemed he didn’t see us. At the locomotive, he stopped for a moment, walked around it, and continued along the cars.

“You should sit down!” the doctor shouted, but he didn’t answer.

These were the first to terrify us. And then more and more often they began to appear on the tracks and around them, and the whole field, bathed in the motionless red glow of fires, began to writhe as if alive, erupting in loud cries, wails, curses, and moans. These dark mounds writhed and crawled like sleepy crayfish released from a basket, splayed, strange, hardly resembling humans in their torn, vague movements and heavy immobility. Some were voiceless and obedient, others moaned, howled, swore, and hated us, who were saving them, so passionately, as if we had created this bloody, indifferent night, and their loneliness amidst the night and the corpses, and these terrible wounds. There was no more room in the cars, and all our clothes were wet with blood, as if we had stood for a long time under a bloody rain, but the wounded kept being carried, and the revived field continued to writhe just as wildly.

Some crawled by themselves, others approached, swaying and falling. One soldier almost ran up to us. His face was crushed, and only one eye remained, burning wildly and terribly, and he was almost naked, as if from a bath. Pushing me, he found the doctor with his eye and quickly grabbed him by the chest with his left hand.

“I’ll punch you in the face!” he shouted and, shaking the doctor, added a long and acrid cynical curse. “I’ll punch you in the face! Scum!”

The doctor broke free and, stepping towards the soldier, choking, shouted:

“I’ll have you court-martialed, scoundrel! To the brig! You’re hindering my work! Scoundrel! Animal!”

They were pulled apart, but for a long time the soldier kept shouting:

“Scum! I’ll punch you in the face!”

I was already losing strength and went to the side to smoke and rest. From the dried blood, my hands felt like they were covered in black gloves, and my fingers bent with difficulty, dropping cigarettes and matches. And when I lit up, the tobacco smoke seemed so new and strange to me, with a completely peculiar taste that I had never experienced before or since. Then the medical student, the one who had come here, approached me, but it seemed to me that I had seen him several years ago, and I could never remember where. He walked firmly, as if marching, and looked through me somewhere further and higher.

“And they’re asleep,” he said as if completely calm.

I flared up, as if the reproach concerned me.

“You forget that they fought like lions for ten days.”

“And they’re asleep,” he repeated, looking through me and higher. Then he bent closer to me and, threatening with his finger, continued just as dryly and calmly:

“I’ll tell you. I’ll tell you.”

“What?”

He kept bending lower to me, significantly threatening with his finger and repeating as if a completed thought:

“I’ll tell you. I’ll tell you. Tell them.”

And, still looking at me sternly and once again threatening with his finger, he took out a revolver and shot himself in the temple. And this did not surprise or frighten me at all. Shifting the cigarette to my left hand, I touched the wound with my finger and went to the cars.

“The student shot himself. He seems to be still alive,” I said to the doctor.

He clutched his head and groaned:

“Oh, damn him!… But we have no room. That one there will shoot himself too. And I give you my honest word,” he shouted angrily and menacingly. “Me too! Yes! And I ask you — please walk. There’s no room. You can complain if you wish.”

And still shouting, he turned away, and I approached the one who was about to shoot himself. It was an orderly, also, it seemed, a student. He stood with his forehead pressed against the wall of the car, and his shoulder trembled with sobs.

“Stop it,” I said, touching the trembling shoulder.

But he didn’t turn, didn’t answer, and cried. And his neck was young, like the other’s, and also terrifying, and he stood awkwardly splayed, like a drunk person vomiting; and his neck was covered in blood — he must have grabbed it with his hands.

“Well?” I said impatiently.

He recoiled from the car and, with his head down, stooped like an old man, walked somewhere into the darkness, away from all of us. I don’t know why, but I followed him, and we walked for a long time, always off to the side, away from the cars. It seemed he was crying; and I grew bored and wanted to cry myself.

“Stop!” I shouted, stopping.

But he walked on, dragging his feet heavily, stooped, resembling an old man, with his narrow shoulders and shuffling gait. And soon he disappeared into the reddish haze, which seemed like light but illuminated nothing. And I was left alone.

To my left, already far from me, a row of dim lights drifted by — the train had left. I was alone among the dead and dying. How many were still left? Everything near me was still and dead, but further on, the field writhed as if alive — or perhaps it only seemed so because I was alone. But the moan did not subside. It spread across the ground — thin, hopeless, like a child’s cry or the whimper of a thousand abandoned and freezing puppies. Like a sharp, endless icy needle, it entered my brain and slowly moved back and forth, back and forth…

Sixth Excerpt

…these were ours. Amidst that strange confusion of movements that had been plaguing both armies, ours and the enemy’s, for the last month, breaking all orders and plans, we were sure that the enemy, specifically the Fourth Corps, was advancing on us. And everything was already ready for the attack when someone clearly distinguished our uniforms through binoculars, and ten minutes later, the guess turned into a calm and happy certainty: these were ours. And they, apparently, recognized us: they moved towards us completely calmly; in this peaceful movement, the same happy smile of an unexpected meeting was felt, just like ours.

And when they started shooting, for a while we couldn’t understand what it meant, and we were still smiling — under a hail of shrapnel and bullets that showered us and immediately took out hundreds of men. Someone shouted about a mistake, and — I distinctly remember this — we all saw that it was the enemy, and that the uniform was theirs, not ours, and we immediately returned fire. Probably fifteen minutes after the start of this strange battle, both my legs were torn off, and I came to in the infirmary, after the amputation.

I asked how the battle ended, but I received an evasive, reassuring answer, from which I understood that we were defeated; and then, legless, I was seized with joy that I would now be sent home, that I was alive after all — alive — for a long time, forever. And only a week later did I learn some details that again pushed me towards doubt and a new, as yet untried fear.

Yes, it seems it was our own — and my legs were torn off by our own grenade, fired from our own gun by our own soldier. And no one could explain how it happened. Something happened, something obscured their vision, and two regiments of the same army, standing a verst apart, mutually annihilated each other for a whole hour, in full confidence that they were dealing with the enemy. And they recalled this incident reluctantly, in half-words, and — most astonishingly, it was felt that many of those who spoke still didn’t realize the mistake. Rather, they admit it, but think it happened later, and at the beginning they really were dealing with the enemy, who had somehow disappeared in the general panic and exposed us to our own shells. Some openly spoke about it, giving precise explanations that seemed plausible and clear to them. I myself still cannot say with full certainty how this strange misunderstanding began, as I saw our red uniform just as clearly at first, and then theirs, orange. And somehow very quickly everyone forgot about this incident, so much so that they spoke of it as a real battle, and many entirely sincere reports were written and sent in that sense; I read them already at home. Towards us, wounded in this battle, the attitude was at first somewhat strange — we seemed to be pitied less than other wounded, but soon this too smoothed over. And only new incidents, similar to the one described, and the fact that in the enemy army two detachments indeed almost completely annihilated each other, resorting to hand-to-hand combat at night, gives me the right to think that there was a mistake.

Our doctor, the one who performed the amputation, a dry, bony old man, reeking of iodoform, tobacco smoke, and carbolic acid, always smiling through his yellowish-gray, sparse mustache, told me, narrowing his eyes:

“It’s your good fortune that you’re going home. Something’s wrong here.”

“What’s wrong?”

“Just that. Something’s wrong. In our time it was simpler.”

He had participated in the last European war, almost a quarter of a century ago, and often remembered it with pleasure. But he didn’t understand this one and, as I noticed, was afraid of it.

“Yes, something’s wrong,” he sighed and frowned, disappearing into a cloud of tobacco smoke, “I myself would leave here if I could.”

And, leaning towards me, he whispered through his yellow, smoke-stained mustache:

“Soon there will come a moment when no one will leave here. Yes. Neither I, nor anyone.”

And in his close, old eyes, I saw the same fixed, dully stunned look. And something terrifying, unbearable, like the collapse of a thousand buildings, flashed in my head, and, growing cold with horror, I whispered:

“The red laugh.”

And he was the first to understand me. He nodded his head hastily and confirmed:

“Yes. The red laugh.”

Sitting very close to me and looking around, he whispered rapidly, moving his sharp, graying beard like an old man:

“You’ll be leaving soon, and I’ll tell you. Have you ever seen a fight in a madhouse? No? Well, I have. And they fought like healthy people. You understand, like healthy people!”

He repeated this phrase meaningfully several times.

“So what?” I asked in a similar whisper, frightened.

“Nothing. Like healthy people!”

“The red laugh,” I said.

“They were doused with water.”

I remembered the rain that had frightened us so much, and got angry:

“You’re out of your mind, doctor!”

“No more than you. In any case, no more.”

He clasped his sharp, elderly knees with his hands and chuckled, and, glancing at me over his shoulder, still carrying the echoes of that unexpected and heavy laughter on his dry lips, he slyly winked at me several times, as if only the two of us knew something very funny that no one else did. Then, with the solemnity of a professor of magic performing tricks, he raised his hand high, smoothly lowered it, and carefully touched with two fingers the spot on the blanket where my legs would have been if they hadn’t been amputated.

“And do you understand this?” he asked mysteriously.

Then, just as solemnly and meaningfully, he swept his hand over the rows of beds where the wounded lay and repeated:

“And can you explain this?”

“The wounded,” I said. “The wounded.”

“The wounded,” he repeated like an echo. “The wounded. Without legs, without arms, with torn bellies, crushed chests, eyes torn out. Do you understand this? Very glad. So you’ll understand this too…?”

With a flexibility unexpected for his age, he bent down and stood on his hands, balancing his legs in the air. His white gown fell down, his face was flushed with blood, and, persistently looking at me with a strange, inverted gaze, he uttered disjointed words with difficulty:

“And this… do you also… understand?”

“Stop it,” I whispered, frightened. “Or I’ll scream.”

He flipped over, assumed a natural position, sat down again by my bed, and, puffing, remarked instructively:

“And no one understands this.”

“Yesterday they shot again.”

“And they shot yesterday. And they shot the day before yesterday,” he nodded affirmatively.

“I want to go home!” I said with anguish. “Doctor, dear, I want to go home. I can’t stay here. I’m starting to stop believing that there’s a home where it’s so good.”

He thought I had no legs. I loved riding my bicycle so much, walking, running, and now I have no legs. I used to bounce my son on my right leg, and he would laugh, and now… Damn you! Why would I go! I’m only thirty years old… Damn you!

And I sobbed, sobbed, remembering my dear legs, my swift, strong legs. Who took them from me, who dared to take them!

“Listen,” the doctor said, looking away. “Yesterday I saw: a mad soldier came to us. An enemy soldier. He was almost naked, beaten, scratched, and hungry like an animal; he was covered in hair, like all of us, and looked like a savage, a primitive man, an ape. He waved his arms, grimaced, sang and shouted, and tried to fight. They fed him and drove him back — into the field. What are we to do with them? Day and night, ragged, ominous ghosts they roam the hills back and forth, and in all directions, without a road, without a purpose, without shelter. They wave their arms, laugh, shout, and sing, and when they meet, they get into a fight, or perhaps they don’t see each other and pass by. What do they eat? Probably nothing, or perhaps corpses, along with the beasts, along with those fat, well-fed feral dogs that fight and whine all night on the hills. At night, like birds awakened by a storm, like deformed moths, they gather to the fire, and one only needs to build a bonfire against the cold, so that in half an hour a dozen loud, ragged, wild silhouettes, resembling chilled apes, will grow around it. They are sometimes shot by mistake, sometimes on purpose, driven to patience’s end by their senseless, frightening cries…”

“I want to go home!” I cried, covering my ears.

And, as if through cotton, muffled and ghostly, new terrible words pounded my tormented brain:

“…There are many of them. They die by the hundreds in abysses, in wolf pits prepared for the healthy and intelligent, on the remnants of barbed wire and stakes; they interfere in proper, rational battles and fight like heroes, always at the front, always fearless; but they often strike their own. I like them. Right now I am only going mad, and that’s why I’m sitting and talking to you, but when reason finally leaves me, I will go out into the field — I will go out into the field, I will raise a cry — I will raise a cry, I will gather these brave ones around me, these knights without fear, and I will declare war on the whole world. In a joyful crowd, with music and songs, we will enter cities and villages, and wherever we pass, everything will be red, everything will spin and dance like fire. Those who have not died will join us, and our brave army will grow like an avalanche and cleanse this whole world. Who said that one cannot kill, burn, and plunder?…”

He was already shouting, this mad doctor, and with his cry he seemed to awaken the dormant pain of those whose chests and bellies were torn, whose eyes were gouged out, whose legs were severed. The ward filled with a broad, scraping, weeping moan, and from everywhere pale, yellow, emaciated faces turned towards us, some without eyes, others in such monstrous disfigurement, as if they had returned from hell. And they moaned and listened, and through the open door, the black, formless shadow that had risen over the world cautiously peered in, and the mad old man shouted, stretching out his arms: “Who said that one cannot kill, burn, and plunder? We will kill, and plunder, and burn. A merry, carefree band of brave men — we will destroy everything: their buildings, their universities, and museums; cheerful fellows, full of fiery laughter — we will dance on the ruins. I will declare a madhouse our fatherland; our enemies and madmen — all those who have not yet gone mad; and when, great, invincible, joyful, I reign over the world, its sole lord and master — what a merry laugh will resound throughout the universe!

“Red laugh!” I cried, interrupting. “Save me! Again I hear the red laugh!”

“Friends!” the doctor continued, addressing the moaning, disfigured shadows. “Friends! We will have a red moon and a red sun, and the beasts will have red, merry fur, and we will skin those who are too white, who are too white… Have you tried drinking blood? It’s a little sticky, it’s a little warm, but it’s red, and it has such a merry red laugh!…”

Seventh Excerpt

…it was ungodly, it was lawless. The Red Cross is respected throughout the world as sacred, and they saw that this was a train not with soldiers, but with harmless wounded, and they should have warned about the planted mine. Unfortunate people, they were already dreaming of home…

Eighth Excerpt

…around the samovar, around a real samovar, from which steam billowed like from a locomotive — even the lamp glass fogged up a little: so strongly did the steam rise. And the cups were the same, blue on the outside and white on the inside, very beautiful cups that we received as a wedding gift. My wife’s sister gave them to us — she’s a very sweet and kind woman.

“Are they all intact?” I asked incredulously, stirring sugar in my glass with a clean silver spoon.

“One broke,” my wife said absently: she was holding the faucet open at the time, and hot water ran beautifully and easily from it.

I laughed.

“What’s wrong with you?” my brother asked.

“Nothing. Well, take me to the study again. Do a hero a favor! You’ve been idle without me, now it’s over, I’ll whip you into shape,” and I jokingly, of course, sang: “Bravely we rush to the foes, to battle, friends…”

They understood the joke and smiled too, only my wife didn’t lift her face: she was wiping the cups with a clean embroidered towel. In the study, I again saw the light blue wallpaper, the lamp with the green shade, and the table on which the carafe of water stood. And it was a little dusty.

“Pour me some water from here,” I ordered cheerfully.

“You just drank tea.”

“It’s fine, it’s fine, pour it. And you,” I said to my wife, “take our son and sit in that room for a bit. Please.”

And in small sips, enjoying it, I drank the water, while my wife and son sat in the next room, and I couldn’t see them.

“Alright, good. Now come here. But why isn’t he going to bed so late?”

“He’s happy you’re back. Darling, go to your father.”

But the child cried and hid at his mother’s feet.

“Why is he crying?” I asked in bewilderment and looked around. “Why are you all so pale, and silent, and following me like shadows?”

My brother laughed loudly and said:

“We’re not silent.”

And my sister repeated:

“We’ve been talking the whole time.”

“I’ll see about dinner,” my mother said and hastily left.

“Yes, you are silent,” I repeated with unexpected certainty. “Since morning I haven’t heard a word from you, only I am chattering, laughing, rejoicing. Aren’t you happy for me? And why do you all avoid looking at me, have I changed so much? Yes, so much. I don’t even see mirrors. Did you remove them? Give me a mirror.”

“I’ll bring it now,” my wife replied and didn’t return for a long time, and the maid brought the mirror. I looked into it, and — I had already seen myself in the train car, at the station — it was the same face, a little older, but perfectly ordinary. And they, it seemed, for some reason expected me to cry out and faint — so happy were they when I calmly asked:

“What’s so unusual about this?”

Laughing louder, my sister hastily left, and my brother said confidently and calmly:

“Yes. You’ve changed little. A bit bald.”

“Be thankful that your head remained,” I replied indifferently. “But where are they all running off to: one after another. Wheel me around the rooms again. What a comfortable chair, completely silent. How much did you pay? And I won’t spare money: I’ll buy myself such legs, better… A bicycle!”

It hung on the wall, still quite new, only with deflated tires. A piece of mud had dried onto the rear tire — from the last time I rode it. My brother was silent and didn’t move the chair, and I understood this silence and this hesitation.

“Only four officers in our regiment remained alive,” I said grimly. “I am very happy… And you take this one, take it tomorrow.”

“Alright, I’ll take it,” my brother obediently agreed. “Yes, you are happy. Half the city is in mourning. And the legs, really…”

“Of course. I’m not a postman.”

My brother suddenly stopped and asked:

“And why is your head shaking?”

“Trifles. It’ll pass, the doctor said!”

“And your hands too?”

“Yes, yes. And my hands. Everything will pass. Please, keep pushing, I’m tired of standing.”

They upset me, these dissatisfied people, but joy returned to me again when they began to prepare my bed — a real bed, on a beautiful bed, on the bed I bought before my wedding, four years ago. They spread a clean sheet, then plumped the pillows, turned down the blanket — and I watched this solemn ceremony, and tears stood in my eyes from laughter.

“Now undress me and put me in bed,” I said to my wife. “How good!”

“Right away, dear.”

“Hurry up!”

“Right away, dear.”

“What’s wrong with you?”

“Right away, dear.”

She stood behind my back, by the dressing table, and I vainly turned my head to see her. And suddenly she screamed, she screamed as only people scream in war:

“What is this!” And she rushed to me, hugged me, fell beside me, hiding her head near my severed legs, recoiling from them in horror and then clinging again, kissing these stumps and crying.

“What you were! You’re only thirty years old. You were young, handsome. What is this! How cruel people are. Why this? Who needed this? You, my meek, my pitiful, my dear, dear…”

And then, at her cry, they all came running, my mother, and my sister, and the nurse, and they all cried, said something, groveled at my feet and cried so much. And on the doorstep stood my brother, pale, completely white, with a trembling jaw, and shrieked:

“I’ll go crazy here with you all. I’ll go crazy!”

And my mother crawled by the chair and no longer cried, but only wheezed and banged her head against the wheels. And clean, with fluffed pillows, with the blanket turned down, stood the bed, the very one I bought four years ago — before my wedding…

Ninth Excerpt

…I sat in the bath with hot water, while my brother nervously moved about the small room, sitting down, getting up again, grabbing soap, a sheet, holding them close to his nearsighted eyes, and then putting them back. Then he turned to the wall and, picking at the plaster with his finger, continued passionately:

“Just consider: one cannot, with impunity, for tens and hundreds of years, teach compassion, reason, logic — give consciousness. The main thing is consciousness. One can become merciless, lose sensitivity, get used to the sight of blood, and tears, and suffering — like butchers, or some doctors, or soldiers; but how is it possible, having known the truth, to renounce it? In my opinion, it’s impossible. From childhood, I was taught not to torment animals, to be compassionate; all the books I read taught me the same, and I feel agonizing pity for those who suffer in your cursed war. But time passes, and I begin to get used to all these deaths, sufferings, blood; I feel that even in everyday life I am less sensitive, less responsive, and react only to the strongest stimuli — but I cannot get used to the fact of war itself, my mind refuses to understand and explain what is fundamentally insane. A million people gathered in one place and trying to regularize their actions, kill each other, and everyone feels the same pain, and everyone is equally unhappy — what is this, isn’t it madness?”

My brother turned and stared at me questioningly with his nearsighted, slightly naive eyes.

“The red laugh,” I said cheerfully, splashing.

“And I’ll tell you the truth.” My brother trustingly placed his cold hand on my shoulder, but as if frightened that it was bare and wet, quickly withdrew it. “I’ll tell you the truth: I’m very afraid of going mad. I cannot understand what is happening. I cannot understand, and it’s terrible. If only someone could explain it to me, but no one can. You were at war, you saw it — explain it to me.”

“Go to hell!” I replied playfully, splashing.

“There, you too,” my brother said sadly. “No one can help me. It’s terrible. And I stop understanding what is permissible, what is not, what is rational, and what is insane. If I now take you by the throat, first gently, as if caressing, and then tighter, and strangle you — what would that be!”

“You’re talking nonsense. No one does that.”

My brother rubbed his cold hands, smiled quietly, and continued:

“When you were still there, there were nights when I didn’t sleep, couldn’t fall asleep, and then strange thoughts came to me: to take an axe and go kill everyone: mom, sister, servants, our dog. Of course, these were just thoughts, and I would never do it.”

“I hope so,” I smiled, splashing.

“I also fear knives, everything sharp, shiny: it seems to me that if I take a knife in my hands, I will certainly stab someone. After all, why not stab if the knife is sharp?”

“A sufficient reason. What a strange fellow you are, brother! Let some more hot water in.”

My brother turned on the tap, let in water, and continued:

“I also fear crowds, people, when many of them gather. When I hear a noise in the street in the evening, a loud cry, I flinch and think that it has already begun… a massacre. When several people stand facing each other and I don’t hear what they’re talking about, it starts to seem to me that they will now scream, rush at each other, and murder will begin, and you know,” he leaned mysteriously towards my ear, “newspapers are full of reports of murders, of some strange murders. It’s nothing that there are many people and many minds — humanity has one mind, and it’s beginning to grow clouded. Feel my head, how hot it is. There’s fire in it. And sometimes it gets cold, and everything in it freezes, stiffens, turns into terrible dead ice. I must go mad, don’t laugh, brother: I must go mad… It’s been a quarter of an hour, it’s time for you to get out of the bath.”

“Just a little more. One minute.”

It felt so good to sit in the bath, like before, and listen to the familiar voice, without dwelling on the words, and see everything familiar, simple, ordinary: the copper, slightly greenish tap, the walls with their familiar pattern, the photography equipment, neatly arranged on the shelves. I’ll take up photography again, capture simple and peaceful scenes and my son: how he walks, how he laughs and plays. I can do that even without legs. And I’ll write again about intelligent books, about new achievements of human thought, about beauty and peace.

“Ho-ho-ho!” I roared, splashing.

“What’s wrong with you?” my brother asked, startled and pale.

“Nothing. Just happy to be home.”

He smiled at me like a child, like a younger brother, though I was three years his senior, and then he pondered — like an adult, like an old man with big, heavy, old thoughts.

“Where to go?” he said, shrugging. “Every day, at approximately the same hour, newspapers close the circuit, and all humanity shudders. This simultaneity of sensations, thoughts, suffering, and horror deprives me of support, and I am like a chip on a wave, like a speck of dust in a whirlwind. I am forcibly torn from the ordinary, and every morning there is one terrible moment when I hang in the air above the black abyss of madness. And I will fall into it, I must fall into it. You don’t know everything yet, brother. You don’t read newspapers, much is hidden from you — you don’t know everything yet, brother.”

And what he said, I considered a somewhat gloomy joke; this was the lot of all those who, in their madness, become close to the madness of war and warned us. I considered it a joke — as if I had forgotten at that moment, splashing in the hot water, everything I had seen there.

“Well, let them hide it, I need to get out of the bath,” I said lightheartedly, and my brother smiled and called the servant, and together they lifted me out and dressed me. Then I drank fragrant tea from my ribbed glass and thought that one could live without legs, and then I was taken to my study, to my table, and I prepared to work.

Before the war, I reviewed foreign literature for a journal, and now, within arm’s reach, lay a pile of these lovely, beautiful books in yellow, blue, brown covers. My joy was so great, the pleasure so deep, that I dared not begin reading and only shuffled through the books, gently caressing them with my hand. I felt a smile spread across my face, probably a very foolish smile, but I couldn’t suppress it, admiring the fonts, the vignettes, the austere and beautiful simplicity of the design. How much intelligence and sense of beauty there was in all of this! How many people must have worked, searched, how much talent and taste must have been invested to create even this single letter, so simple and elegant, so intelligent, so harmonious and eloquent in its intertwined strokes.

“Now we must work,” I said seriously, with respect for labor.

And I took up my pen to write a heading — and, like a frog tied on a string, my hand flapped across the paper. The pen poked at the paper, scratched, twitched, uncontrollably slid sideways, and produced ugly lines, broken, crooked, meaningless. And I did not cry out, and I did not move — I grew cold and froze in the awareness of the approaching terrible truth; and my hand jumped across the brightly lit paper, and every finger in it trembled with such hopeless, vivid, insane horror, as if they, these fingers, were still there, at war, and saw the glow and the blood, and heard the moans and cries of unspeakable pain. They had separated from me, they lived, they became ears and eyes, these madly trembling fingers; and, growing cold, unable to cry out or move, I watched their wild dance across the clean, brightly white sheet.

And it was quiet. They thought I was working, and they closed all the doors so as not to disturb me with sound — alone, deprived of the ability to move, I sat in the room and obediently watched my hands tremble.

“It’s nothing,” I said loudly, and in the silence and solitude of the study, my voice sounded hoarse and unpleasant, like a madman’s voice. “It’s nothing. I will dictate. After all, Milton was blind when he wrote his ‘Paradise Regained.’ I can think — that’s the main thing, that’s everything.” And I began to compose a long, intelligent sentence about blind Milton, but the words became jumbled, dropped out as from a bad typeset, and by the time I reached the end of the sentence, I had already forgotten its beginning. I tried to remember then how it started, why I was composing this strange, meaningless sentence about some Milton — and I couldn’t.

“‘Paradise Regained,’ ‘Paradise Regained’,” I repeated and did not understand what it meant.

And then I realized that I was forgetting a lot in general, that I had become terribly absent-minded and confused familiar faces, that even in simple conversation I lost words, and sometimes, even knowing a word, I couldn’t understand its meaning at all. My current day clearly appeared before me: some strange, short, truncated day, like my legs, with empty, mysterious places — long hours of unconsciousness or insensitivity.

I wanted to call my wife, but I forgot her name — this no longer surprised or frightened me. Quietly I whispered:

“Wife!”

The awkward, unfamiliar word, when used in address, sounded softly and died away, eliciting no response. And it was quiet. They were afraid to disturb my work with an incautious sound, and it was quiet — a true scholar’s study, cozy, quiet, conducive to contemplation and creativity. “Dear ones, how they care for me!” I thought, touched.

…And inspiration, holy inspiration, descended upon me. The sun ignited in my head, and its hot creative rays splashed upon the whole world, showering it with flowers and songs. And all night I wrote, knowing no fatigue, freely soaring on the wings of powerful, holy inspiration. I wrote the great, I wrote the immortal — flowers and songs. Flowers and songs…

PART TWO

Tenth Excerpt

…fortunately, he died last week, on Friday. I repeat, it’s a great blessing for my brother. A legless cripple, trembling all over, with a shattered soul, in his mad ecstasy of creation, he was terrible and pathetic. From that very night, for two whole months, he wrote without getting up from his chair, refusing food, crying and swearing when we briefly took him away from the table. With extraordinary speed, he moved his dry pen across the paper, discarding sheets one after another, and just kept writing and writing. He lost sleep, and only twice did we manage to put him to bed for a few hours, thanks to a strong dose of narcotics, and then even anesthesia could not overcome his creative, mad ecstasy. At his request, the windows were covered all day and a lamp burned, creating the illusion of night, and he smoked cigarette after cigarette and wrote. Apparently, he was happy, and I had never seen such an inspired face in healthy people — the face of a prophet or a great poet. He had become extremely emaciated, to the waxy transparency of a corpse or an ascetic, and had completely grayed; he began his insane work still relatively young, and finished it as an old man. Sometimes he hurried to write more than usual, the pen would poke the paper and break, but he didn’t notice it; at such moments, he couldn’t be touched, as the slightest touch would trigger a fit, tears, laughter; at times — very rarely — he would blissfully rest and graciously converse with me, always asking the same questions: who I was, what my name was, and how long I had been involved in literature.

And then he would condescendingly tell, always in the same words, how he had comically feared that he had lost his memory and couldn’t work, and how he had brilliantly refuted this mad assumption by starting his great, immortal work on flowers and songs.

“Of course, I don’t count on the recognition of my contemporaries,” he said proudly yet humbly, placing his trembling hand on a pile of empty sheets, “but the future, the future will understand my idea.”

He never once recalled the war, nor did he once remember his wife and son; the ghostly, endless work absorbed his attention so completely that he hardly seemed aware of anything else. In his presence, one could walk around, talk, and he wouldn’t notice, and not for a moment did his face lose its expression of terrible tension and inspiration. In the silence of the nights, when everyone slept and he alone tirelessly wove the endless thread of madness, he seemed terrifying, and only I and my mother dared to approach him. Once I tried to give him a pencil instead of a dry pen, thinking that perhaps he was actually writing something, but only ugly lines remained on the paper, broken, crooked, meaningless.

And he died at night, at work. I knew my brother well, and his madness was not unexpected for me: the passionate dream of work, which permeated his letters from the war and constituted the entire content of his life upon his return, inevitably had to collide with the powerlessness of his tired, exhausted brain and cause a catastrophe. And I think I managed to quite accurately reconstruct the entire sequence of sensations that led him to his end on that fateful night. Generally, everything I have written here about the war is taken from the words of my deceased brother, often very confused and incoherent; only some individual scenes so indelibly and deeply etched themselves into his brain that I could reproduce them almost verbatim, as he narrated.

I loved him, and his death lies on me like a stone, crushing my brain with its senselessness. To the incomprehensible that shrouds my head like a cobweb, it added another loop and tightened it firmly. Our whole family has gone to the village, to relatives, and I am alone in the whole house — in this small mansion that my brother loved so much. The servants were dismissed; sometimes the janitor from the neighboring house comes in the mornings to light the stoves, and the rest of the time I am alone, like a fly trapped between two window panes, thrashing and breaking myself against some transparent but insurmountable barrier. And I feel, I know, that I cannot escape this house. Now that I am alone, the war possesses me entirely and stands like an incomprehensible riddle, like a terrible spirit that I cannot embody. I give it all sorts of images: a headless skeleton on horseback, some formless shadow born in the clouds and silently embracing the earth, but no image gives me an answer and does not exhaust the cold, constant, dull horror that possesses me.

I don’t understand war and I must go mad, like a brother, like hundreds of people brought back from there. And this doesn’t frighten me. Losing my mind seems honorable to me, like a sentry dying at his post. But the waiting, this slow and steady approach of madness, this momentary feeling of something vast falling into an abyss, this unbearable pain of a tormented thought… My heart has grown numb, it has died, and there is no new life for it, but thought — still alive, still struggling, once strong as Samson, and now defenseless and weak as a child — I pity it, my poor thought. At times, I can no longer bear the torture of these iron hoops crushing my brain; I want irresistibly to run out into the street, into the square where there are people, and shout:

“Stop the war now, or…”

But what “or”? Are there words that could bring them back to reason, words for which there wouldn’t be other equally loud and false words? Or fall to my knees before them and cry? But hundreds of thousands fill the world with their tears, and does that accomplish anything? Or kill myself before their eyes? Kill! Thousands die daily, and does that accomplish anything?

And when I feel my powerlessness like this, a rage overcomes me — the rage of the war that I hate. I want, like that doctor, to burn their houses, with their treasures, with their wives and children, to poison the water they drink; to raise all the dead from their graves and throw the corpses into their unclean dwellings, onto their beds. Let them sleep with them, as with their wives, as with their lovers!

Oh, if only I were the devil! All the horror that hell breathes, I would transplant to their land; I would become the master of their dreams, and when, smiling as they fell asleep, they crossed their children, I would stand before them, black…

Yes, I must go mad, but only quickly. Only quickly…

Excerpt Eleven

…of prisoners, a huddle of trembling, frightened people. When they were led out of the train car, the crowd roared — roared like one huge, malicious dog whose chain was short and flimsy. It roared and then fell silent, breathing heavily — and they walked in a tight cluster, their hands in their pockets, smiling ingratiatingly with pale lips, their feet stepping as if a long stick was about to strike them from behind beneath the knee. But one walked somewhat apart, calm, serious, without a smile, and when my eyes met his black ones, I read in them overt and naked hatred. I clearly saw that he despised me and expected everything from me: if I were to kill him now, unarmed, he would not cry out, he would not defend himself or make excuses; he expected everything from me.

I ran along with the crowd to meet his gaze once more, and I succeeded as they were already entering the house. He entered last, letting his comrades go ahead, and looked at me one more time. And then I saw in his black, large, pupil-less eyes such torment, such an abyss of horror and madness, as if I had looked into the most unfortunate soul on earth.

“Who’s that one, with the eyes?” I asked the convoy guard.

“An officer. Crazy. There are many like him.”

“What’s his name?”

“He’s silent, won’t give his name. And his own don’t know him. Just some stray. They’ve already pulled him from a noose once, but what good is it!..” The convoy guard waved his hand and disappeared behind the door.