The Publication History of Doctor Zhivago

How a banned text, for the possession of which people were recently imprisoned, was published in a million copies, and why the publication of the main Russian novel of the 20th century was stretched over 30 years. We spoke with the poet’s daughter-in-law, literary historian Elena Vladimirovna Pasternak.

On our website you can buy this book via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

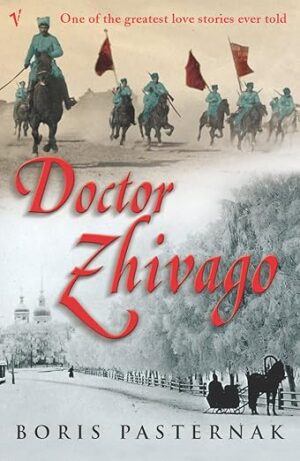

Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

Page Count: 512Year: 1957Products search Zhivago marries the gentle Tonya, but his destiny is tragically entwined with the passionate, elusive Larisa (“Lara”) Antipova, a woman whose life is scarred by an older predator and whose husband transforms into the fearsome Red commander, Strelnikov. As the world fragments into chaos, the doctor struggles to practice his art and preserve […]

€20.00 Login to Wishlist

Imagine: you are riding the metro and secretly reading a book typed on a typewriter. You are stopped, searched, and arrested when the book is found. At best, the book is confiscated, and you are fired from your job. This happened quite recently—about fifty years ago. I later saw those confiscated books in the archive. It’s hard to believe now: after all, we’re talking about Doctor Zhivago.

First Publication

In late 1957, Doctor Zhivago was published in Italian in Milan by the publisher Feltrinelli, to whom Pasternak handed a copy of the manuscript when he realized that printing the book in the USSR was out of the question. Soon after, editions followed in other languages, including Russian (the first Russian edition was published in Holland from a manuscript that had not been corrected by the author).

The circumstances of the novel’s publication in Europe are a separate story, but two circumstances are important for our narrative. First, the text published by Feltrinelli was not authorized; that is, it was not the final author’s text. Second, the publication of Zhivago in the West—both in foreign languages and in Russian—made Pasternak virtually a state criminal and, along with the Nobel Prize awarded to him in 1958, led to the harshest persecution, possibly accelerating his death in May 1960.

No one intended to publish the forbidden novel in his homeland. My husband, Evgeny Borisovich [Pasternak], proposed publishing the book—not in a pirated version, but in the final, author-verified version—every time he visited the Goslitizdat (State Literature Publishing House) for almost three decades. But the Writers’ Union still prohibited everything. For example, in 1965—the last echo of the Thaw—when a large selection of poems was printed in the “Poet’s Library” series and a small book was published by Goslit, Evgeny was passed the words of [Alexey] Surkov: “Publish Zhivago? What, are we supposed to admit that we were fools in 1958, or now, in 1965?”

Then began the terrible freeze, the dead time of the Brezhnev era. From 1965 until the early 1980s, Boris Pasternak was not published in Russia. In 1982, his short prose was successfully published. This was a miracle: Igor Buzylev, the editor-in-chief of Sovetsky Pisatel (Soviet Writer), who was approached by Evgeny, commissioned Alexander Lavrov and Sergey Grechishkin to write commentaries—making the edition scholarly—and, for even more support, asked Dmitry Sergeevich Likhachev to write the preface. Buzylev managed to push the book through in the summer when the bosses were away. He soon died of cancer: perhaps he already knew his diagnosis and therefore feared nothing. Thus, after a long break, a remarkable book with pictures by Leonid Osipovich Pasternak was released: The Childhood of Luvers, Safe Conduct, and other short prose that had not been published since the 1920s-1930s. But, of course, without Doctor Zhivago: the Writers’ Union still adhered to its line on Pasternak, refusing to let him into Soviet literature.

In 1986, there was another writers’ congress. The terrible man Georgy Markov, first secretary of the Writers’ Union board, said in response to journalists’ questions: “No, Doctor Zhivago will never be published in the Soviet Union.” But at the same congress, several writers signed a letter, composed by Evgeny Evtushenko, about the need to restore the Pasternak Museum in Peredelkino. At the same time, after [Sergey] Zalygin’s agreement to publish the novel in the journal Novy Mir, we decided it was time to prepare the text of Zhivago for publication.

Recreating the Book from Words

It was clear that preparing Zhivago for publication was a tremendous task: to collate many typewritten copies with many different corrections, trace all stages of work on the text, and determine the final author’s decisions. Together with Evgeny, and at his request, Vadim Borisov—a young scholar, researcher of Church history, and connoisseur of Silver Age poetry—began to work on this. He was a very beautiful person, known to everyone as Dima. Like many people of his generation, he read the novel from a typewritten manuscript in the sixties, when he was sixteen or seventeen.

The clean copy manuscript of Zhivago was known to us. The first chapters were kept by us; the middle section—with the inscription “To Zina and Lena” [Zinaida Nikolayevna Pasternak and Elena Vladimirovna Pasternak]—was with Zinaida Nikolayevna; the last chapters were with Olga Vsevolodovna [Ivinskaya]. These last chapters were taken during her arrest in 1949 and were stored in a closed fund. But by that time, the KGB had opened its boxes and transferred them to the Central State Archive of Literature and Art (TsGALI). This is where Evgeny and Dima went: besides these final chapters of the novel, the typewritten copies that were seized from various people during searches were also stored there.

We collected many copies that allowed us to trace how Pasternak worked on the book. He would give the manuscript to a typist (Marina Kazimirovna Baranovich retyped the novel many times, and Lyudmila Vladimirovna Stefanovich typed the last chapters; there were other typists as well), and then he would make corrections—in the text already typed on the machine. And he did this many times.

Dima worked with all available manuscripts. These included texts written in ink and pencil, and numerous typewritten copies with corrections, as well as the typed copies of the novel that Boris Leonidovich sent to his friends in letters. He sent them to the most diverse places: to Olga Freidenberg, Sergey Spassky, to Kaisyin Kuliev in exile, and to Ariadna Efron in exile. Incidentally, among other things, Borisov found out that the typewritten manuscript with the final author’s corrections was given to Ariadna Sergeevna Efron.

And then there was the version published by Feltrinelli. The books he printed from the uncorrected typed copy were brought to the USSR: they circulated here, and readers, in turn, made new typed copies from them.

To enable us to work with different versions, Lyova Turchinsky beautifully bound the Zhivago (Feltrinelli’s Russian edition) for us. He inserted blank pages for making corrections: the book was bound interleaved with blank sheets. We compared the corrections from different typed copies. Thus, on each page of this manuscript, Dima’s beautiful handwriting recorded: the text from Marina Kazimirovna Baranovich was such-and-such, the text from Ariadna Efron was such-and-such, the draft, ink, or pencil manuscript was such-and-such, and the text in TsGALI was such-and-such.

Dima thus assembled the final text of the novel based on the author’s corrections from different typed copies.

Million Copies, Nobel Medal

At some point, this titanic work was finished. The text of the novel was ready for publication. Zalygin was afraid to publish the novel, but still said: we will do it in 1988. We submitted the manuscript in 1987. Zalygin commissioned the introductory word from Dmitry Likhachev: his name served as a safeguard for the publication. Likhachev very aptly called his preface: “These were valerian drops for the authorities.” It was needed to say that there was nothing terrible, nothing anti-Soviet, nothing subversive in the novel.

And so, in 1988, the novel Doctor Zhivago was published in the journal Novy Mir, from the first to the fourth issue, from January to April. By announcing and delaying the publication of Zhivago, Zalygin brought the strongly fallen circulation of the magazine up to one million copies; hundreds of thousands of people subscribed, anticipating Pasternak’s novel. After the publication, work on the collected works also began at Goslit.

I remember riding the metro and seeing people everywhere, in every carriage, sitting with the blue booklets of Novy Mir. In the same place where they could previously have been arrested for a manuscript of the novel.

The book had a very strong influence on the dissident movement and, in general, on the generation of those who, like Dima Borisov, secretly read it in samizdat in the sixties and seventies, those who did not want or could not in some way engage in the lie of Soviet life. They worked as janitors, plumbers, published articles under false names, and read Vladimir Solovyov in their basements, like Yury Andreevich in the concluding chapters. And when the novel was published, it became a very important symbol. As the culturologist Anna Shmaina-Velikanova said: “For many of us, Pasternak was an apostle.”

At the end of 1989, a huge exhibition for Pasternak’s centenary opened at the Pushkin Museum.

At this exhibition, Irina Alexandrovna Antonova introduced Evgeny to the Swedish ambassador, Mr. Örjan Berner, who asked if Evgeny Borisovich could come to Stockholm on December 9–10, the days when the Nobel Prize is awarded. Evgeny came to be presented with the Nobel Medal, which Boris Leonidovich had not received.

I remember Rostropovich came to Stockholm during those days. He spoke about how Boris Pasternak was deprived of the right to receive the award bestowed upon him and enjoy the happiness and honor of being a Nobel laureate, and instead was subjected to persecution. I still remember how he played Bach’s sarabande, sitting on the steps of the large wide staircase in the city hall.

The publication of Doctor Zhivago had to be awaited from 1958 to 1988. Thirty years.