The Pit (Yama), Alexander Kuprin: Read FREE Full Text Online (English Translation)

You can now read the full text of one of the most scandalous and candid works of early 20th-century Russian literature—the novella “The Pit” (Yama) by Alexander Kuprin. This uncompromising, naturalistic study of the world of prostitution is available for online reading here in a high-quality English translation.

Immerse yourself in the lives of the young women in a provincial brothel, where Kuprin exposed social sores and the hypocrisy of society with brutal honesty. Start reading the work that once caused a “deafening scandal” due to its unprecedented naturalism. Read instantly, no download required. This exclusive free access is your gateway to the world of great Russian authors and their works.

You can also buy this book from us in the definitive paperback edition via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

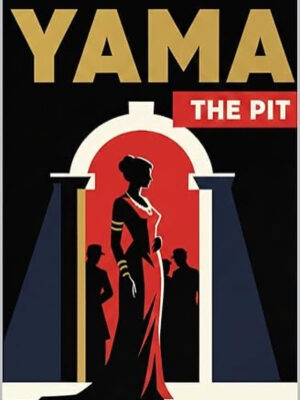

Yama: The Pit by Alexander Kuprin

Page Count: 378Year: 1909READ FREEProducts search “The Pit” is Kuprin’s most tragic work, which once had the effect of a bombshell among readers and critics, and even now, it shocks with its power and merciless realism. The sad story of the inhabitants of a mid-level brothel is told with almost photographic precision. The characters of the “night butterflies,” their […]

€16.00 Login to Wishlist

First published in 1909, in “Zemlya”

Almanak, Russian Empire

This book is in the public domain

Reprint by Publishing House №10

Publication date July 14, 2025

Translation from Russian

370 Pages, Font 12 pt, Bookman Old Style

Electronic edition, File size 808 KB

Cover design, Translate by Yulia Basharova

Copyright© Yulia Basharova 2025. All rights reserved

Table of Contents

PART ONE

PART TWO

PART THREE

PART ONE

I know many will find this story immoral and indecent; nevertheless, I wholeheartedly dedicate it to mothers and youth. A. K.

I

A long, long time ago, long before railways, on the furthest outskirts of a large southern city, generations of coachmen lived — state-employed and freelance. That’s why the entire area was called Yamskaya Sloboda, or simply Yamskaya, Yamki, or, even shorter, Yama. Later, when steam power rendered horse-drawn transport obsolete, this wild coachman tribe gradually shed their unruly ways and daring customs, turning to other occupations, dispersing and scattering. But for many years — even to this day — Yama retained a dark reputation as a place of revelry, drunkenness, brawls, and danger at night.

It somehow happened that on the ruins of those ancient, established nests, where once rosy-cheeked, boisterous soldiers’ wives and dark-browed, plump Yama widows secretly traded vodka and casual love, openly recognized brothels gradually began to emerge. These were permitted by the authorities, overseen by official supervision, and subject to deliberately strict rules. By the end of the 19th century, both streets of Yama — Big Yamskaya and Small Yamskaya — were entirely occupied, on both sides, exclusively by houses of tolerance. No more than five or six private houses remained, but even these housed taverns, alehouses, and general stores, serving the needs of Yama prostitution.

The way of life, morals, and customs were almost identical in all thirty-odd establishments, the only difference being the fee charged for temporary love, and consequently, in some minor external details: the selection of more or less beautiful women, the comparative elegance of costumes, the splendor of the premises, and the luxury of the furnishings.

The most luxurious establishment was Treppel’s, at the entrance to Big Yamskaya, the first house on the left. This was an old firm. Its current owner bore a completely different surname and was a city councilor and even a member of the city administration. The two-story house, green and white, was built in a pseudo-Russian, mocking, “Ropet” style, featuring ridge-boards, carved window frames, rooster figures, and wooden “towels” (decorative elements) edged with wooden lace. There was a carpet with a white runner on the staircase; in the entryway, a stuffed bear held a wooden dish for calling cards in its outstretched paws. The ballroom had parquet flooring, crimson silk heavy curtains and lace on the windows, and white-and-gold chairs and mirrors in gilded frames along the walls. There were two private rooms with carpets, sofas, and soft satin ottomans. The bedrooms featured blue and pink lanterns, fine silk blankets, and clean pillows. The inhabitants were dressed in open ball gowns trimmed with fur, or in expensive masquerade costumes of hussars, pages, fisherwomen, or high school girls, and most of them were Baltic German women — large, fair-skinned, busty, beautiful women. At Treppel’s, a visit cost three rubles, and a whole night cost ten.

Three two-ruble establishments — Sofya Vasilyevna’s, “Old Kyiv,” and Anna Markovna’s — were somewhat shabbier, poorer. The remaining houses on Big Yamskaya were one-ruble establishments; they were even worse furnished. And on Small Yamskaya, which was frequented by soldiers, petty thieves, artisans, and generally common folk, and where they charged fifty kopecks or less, it was utterly dirty and meager: the hall floor was uneven, peeled, and splintered, the windows were covered with red calico scraps. The bedrooms, like stalls, were divided by thin partitions that didn’t reach the ceiling, and on the beds, on top of matted straw mattresses, lay crumpled, haphazardly thrown, torn, time-darkened, stained sheets and ragged flannel blankets. The air was sour and smoky, with a mixture of alcoholic fumes and the smell of human excretions. The women, dressed in colorful chintz rags or sailor costumes, were mostly hoarse or nasal, with partially sunken noses, with faces bearing traces of yesterday’s beatings and scratches, and naïvely painted with the help of a spittle-moistened red cigarette box.

Year-round, every evening — with the exception of the last three days of Holy Week and the eve of Annunciation (when “the bird does not build a nest and the shorn maiden does not braid her hair,” a Russian proverb meaning no work is done on this day) — as soon as darkness fell, hanging red lanterns were lit in front of each house, above the tent-like carved entrances. The street felt like a holiday, like Easter: all the windows were brightly lit, cheerful music of violins and pianos drifted through the panes, and cabs constantly arrived and departed. In all houses, the front doors were wide open, and through them, from the street, one could see: a steep staircase, and a narrow corridor above, and the white sparkle of a multi-faceted lamp reflector, and the green walls of the entryway painted with Swiss landscapes. Until morning, hundreds and thousands of men ascended and descended these staircases. Everyone came here: decrepit, drooling old men seeking artificial stimulation, and boys — cadets and high school students — almost children; bearded family fathers, respected pillars of society in gold spectacles, and newlyweds, and loving fiancés, and venerable professors with famous names, and thieves, and murderers, and liberal lawyers, and strict guardians of morality — teachers, and progressive writers — authors of ardent, passionate articles on women’s equality, and detectives, and spies, and escaped convicts, and officers, and students, and social democrats, and anarchists, and paid patriots; shy and impudent, sick and healthy, those experiencing a woman for the first time, and old debauchees, worn out by all kinds of vice; clear-eyed beauties and deformities, maliciously disfigured by nature, deaf-mutes, blind, noseless, with flabby, sagging bodies, with foul breath, bald, trembling, covered with parasites — pregnant, hemorrhoidal “apes.” They came freely and simply, as if to a restaurant or a train station, sat, smoked, drank, convulsively pretended to be cheerful, danced, performing disgusting movements imitating the act of sexual love. Sometimes carefully and for a long time, sometimes with crude haste, they chose any woman and knew in advance that they would never be refused. They impatiently paid money in advance and on a public bed, still warm from the predecessor’s body, aimlessly performed the greatest and most beautiful of world mysteries — the mystery of the genesis of new life. And the women, with indifferent readiness, with monotonous words, with learned professional movements, satisfied, like machines, their desires, only to immediately after them, on the same night, with the same words, smiles, and gestures, receive a third, fourth, tenth man, often already waiting his turn in the common room.

Thus the whole night passed. Towards dawn, Yama gradually quieted down, and the bright morning found it deserted, spacious, immersed in sleep, with tightly closed doors and thick shutters on the windows. And before evening, the women would wake up and prepare for the next night.

And so, endlessly, day after day, month after month, and year after year, they lived in their public “harems” a strange, improbable life: cast out by society, cursed by family, victims of societal temperament, a cesspool for the overflow of urban sensuality, and ironically, guardians of family honor — four hundred foolish, lazy, hysterical, barren women.

II

Two o’clock in the afternoon. In Anna Markovna’s secondary, two-ruble establishment, everything was deep in slumber. The large square hall with mirrors in gilded frames, with two dozen plush chairs neatly arranged along the walls, with oleographic paintings by Makovsky, “Boyar Feast” and “Bathing,” with a crystal chandelier in the middle — it too slept, and in the silence and twilight, it seemed unusually pensive, strict, and strangely sorrowful. Yesterday here, as every evening, the lights blazed, raucous music rang out, blue tobacco smoke wavered, and pairs of men and women whirled, swaying their hips and kicking their legs high. And the entire street glowed from outside with red lanterns above the entrances and light from the windows, bustling until morning with people and carriages.

Now the street was empty. It glowed solemnly and joyfully in the summer sun. But in the hall, all the curtains were drawn, making it dark, cool, and especially desolate, as empty theaters, riding arenas, and courtrooms can be in the middle of the day.

The piano gleamed dully with its black, curved, glossy side; the yellow, old, time-worn, broken, chipped keys glowed faintly. The stale, motionless air still held yesterday’s scent; it smelled of perfume, tobacco, the sour dampness of a large uninhabited room, then the sweat of unhealthy and unclean female bodies, powder, borothymol soap, and dust from the yellow mastic with which the parquet had been polished yesterday. And with a strange charm, the scent of fading marsh grass mingled with these smells. Today was Trinity Sunday. According to ancient custom, the housemaids of the establishment, early in the morning while their young ladies were still asleep, bought a whole cartload of sedge from the market and scattered its long, crunchy-underfoot, thick grass everywhere: in the corridors, in the private rooms, in the hall. They also lit lamps before all the icons. The girls, by tradition, dared not do this with their hands, defiled by the night.

And the yardman had adorned the carved, Russian-style entrance with two freshly cut birch trees. Similarly, in all the houses, thin white trunks with sparse, dying greenery graced the porches, railings, and doors outside.

Quiet, empty, and sleepy throughout the house. One could hear cutlets being chopped for dinner in the kitchen. One of the girls, Lyubka, barefoot, in a chemise, with bare arms, unattractive, freckled, but strong and fresh of body, went out into the inner courtyard. Last night she had only had six temporary guests, but no one had stayed the night with her, and so she had slept wonderfully, sweetly alone, completely alone, on a wide bed. She had risen early, at ten o’clock, and gladly helped the cook wash the kitchen floor and tables. Now she was feeding the chained dog, Amur, with scraps of meat and sinews. The large ginger dog with long, shiny fur and a black muzzle would either jump on the girl with its front paws, pulling the chain tight and snorting from choking, or, with its whole back and tail wiggling, would lower its head to the ground, wrinkle its nose, smile, whine, and sneeze with excitement. And she, teasing him with the meat, shouted at him with feigned strictness:

“Well, you idiot! I’ll give it to you! How dare you?”

But she was genuinely happy about Amur’s excitement and affection, and her momentary power over the dog, and that she had slept well and spent the night without a man, and about Trinity Sunday, from vague childhood memories, and the sparkling sunny day, which she so rarely got to see.

All the night’s guests had already departed. The most business-like, quiet, everyday hour was approaching.

In the proprietress’s room, coffee was being drunk. A company of five people. The proprietress herself, in whose name the house was registered — Anna Markovna. She was almost sixty. She was very short, but round and fat: one could imagine her by envisioning three soft, gelatinous spheres — large, medium, and small — squeezed into each other without gaps; these were her skirt, torso, and head. Strangely, her eyes were pale blue, girlish, even childlike, but her mouth was old, with a weakly drooping, moist, crimson lower lip. Her husband — Isay Savvich — was also a small, gray-haired, quiet, silent old man. He was under his wife’s thumb; he had been a doorman in this very house back when Anna Markovna served as housekeeper here. He had taught himself to play the violin to be of some use, and now in the evenings he played dances, as well as a funeral march for boisterous shop clerks eager for drunken tears.

Then there were two housekeepers — the senior and the junior. The senior — Emma Eduardovna. She was a tall, full-figured brunette, about forty-six, with a fatty goiter of three chins. Her eyes were surrounded by dark, hemorrhoidal circles. Her face widened downwards like a pear, from the forehead to the cheeks, and was of an earthy complexion; her eyes were small, black; her nose aquiline, her lips strictly pursed; her facial expression calmly authoritative. It was no secret to anyone in the house that in a year or two, Anna Markovna, upon retirement, would sell her the establishment with all rights and furnishings, receiving part in cash and part in installments by promissory note. Therefore, the girls honored and feared her as much as the proprietress. She personally beat those who misbehaved, beating them cruelly, coldly, and calculatingly, without changing her calm expression. Among the girls, she always had a favorite, whom she tormented with her demanding love and fantastic jealousy. And this was much harder than the beatings.

The other was named Zosya. She had just risen from the ranks of ordinary girls. The girls still referred to her impersonally, flatteringly, and familiarly as “the little housekeeper.” She was thin, fidgety, slightly cross-eyed, with a rosy complexion and a curly “lamb” hairstyle; she adored actors, primarily fat comedians. She treated Emma Eduardovna with obsequiousness.

Finally, the fifth person — the local police precinct supervisor, Kerbesh. He was an athletic man; he was somewhat bald, had a fan-shaped ginger beard, bright blue sleepy eyes, and a thin, slightly hoarse, pleasant voice. Everyone knew that he had previously served in the detective department and was a terror to crooks thanks to his tremendous physical strength and cruelty during interrogations.

He had several dark deeds on his conscience. The whole city knew that two years ago he had married a wealthy seventy-year-old woman, and last year he had strangled her; however, he somehow managed to hush up the case. And the other four also had seen a few things in their eventful lives. But, just as old-fashioned duelists felt no remorse recalling their victims, so too did these people view the dark and bloody events of their past as inevitable minor professional inconveniences.

They drank coffee with rich melted cream, the precinct supervisor with Benedictine. But he wasn’t really drinking; he was just pretending to do them a favor.

“So, Foma Fomich?” the proprietress asked solicitously. “This matter is not worth an empty egg… You just need to say the word…”

Kerbesh slowly sipped half a shot glass of liqueur, gently swished the oily, sharp, strong liquid over his palate with his tongue, swallowed it, unhurriedly washed it down with coffee, and then ran the ring finger of his left hand over his mustache, right and left.

“Think for yourselves, Madame Schoibes,” he said, looking at the table, spreading his hands, and squinting, “think of the risk I am exposing myself to here! The girl was fraudulently lured into this… into whatcha-ma-call-it… well, in short, into a house of tolerance, to put it elegantly. Now her parents are looking for her through the police. All right. She goes from one place to another, from the fifth to the tenth… Finally, the trail leads to you, and most importantly — think! — in my precinct! What can I do?”

“Mr. Kerbesh, but she’s of legal age,” said the proprietress.

“They are of legal age,” confirmed Isay Savvich. “They signed a receipt that they willingly…”

Emma Eduardovna said in a bass voice, with cold certainty: “By God, she’s like a dear daughter here.”

“But I’m not talking about that,” the precinct supervisor grumbled annoyedly. “You need to understand my position… It’s my duty. Good heavens, I already have enough trouble as it is!”

The proprietress suddenly stood up, shuffled her slippers toward the door, and said, winking at the precinct supervisor with a lazy, expressionless, pale blue eye: “Mr. Kerbesh, I would like to ask you to look at our alterations. We want to expand the premises a bit.”

“Ah! With pleasure…”

Ten minutes later, both returned, not looking at each other. Kerbesh’s hand crinkled a brand new hundred-ruble note in his pocket. The conversation about the seduced girl was not resumed. The precinct supervisor, hastily finishing his Benedictine, complained about the current decline in morals:

“My son, Pavel, a high school student — the scoundrel comes and declares: ‘Dad, the students are calling me names because you’re a policeman, and you work on Yamskaya, and you take bribes from brothels.’ Well, for God’s sake, Madame Schoibes, isn’t that insolence?”

“Oh dear, oh dear!… And what bribes are these?… It’s the same for me…”

“I tell him: ‘Go, you rogue, and tell the director that this must stop, otherwise Daddy will report all of you to the regional chief.’ What do you think? He comes back and says: ‘I’m no longer your son — find yourself another son.’ What an argument! Well, I gave him a good thrashing! Oh-ho-ho! Now he doesn’t want to talk to me. Well, I’ll show him yet!”

“Oh, don’t even tell me,” sighed Anna Markovna, letting her crimson lower lip droop and her pale eyes cloud over. “Our Berta — she’s at Fleischer’s gymnasium — we deliberately keep her in the city, with a respectable family. You understand, it’s awkward, after all. And suddenly she brings such words and expressions from the gymnasium that I just turned all red.”

“By God, Annushka turned all red,” confirmed Isay Savvich.

“You would turn red!” the precinct supervisor hotly agreed. “Yes, yes, yes, I understand you. But, good heavens, where are we going! Where are we heading? I ask you, what do these revolutionaries and various students, or… what are they called?… want to achieve? And let them blame themselves. Depravity everywhere, morals declining, no respect for parents. They should be shot.”

“Oh, we had a case the day before yesterday,” Zosya interjected fussily. “A guest came, a fat man…”

“Don’t chatter,” Emma Eduardovna snapped at her sternly in brothel jargon, having listened to the precinct supervisor, piously nodding her head tilted to the side. “You’d better go arrange breakfast for the young ladies.”

“And you can’t rely on a single person,” the proprietress grumbled on. “Every servant is a bitch, a cheat. And the girls only think about their lovers. Only about having their own pleasure. And they don’t think about their duties.”

An awkward silence. A knock on the door. A thin female voice spoke from the other side: “Little housekeeper! Take the money and give me my stamps. Petya has left.”

The precinct supervisor stood up and straightened his saber.

“Well, it’s time for duty. All the best, Anna Markovna. All the best, Isay Savvich.”

“Perhaps another shot, for the road?” the nearsighted Isay Savvich poked across the table.

“Thank you. I can’t. Fully supplied. My regards!…”

“Thank you for the company. Do drop by.”

“Your guests. Goodbye.”

But at the door, he stopped for a minute and said significantly: “Still, my advice to you: you’d better get rid of this girl somewhere beforehand. Of course, it’s your business, but as a good acquaintance — I’m warning you.”

He left. When his footsteps faded on the stairs and the front door slammed behind him, Emma Eduardovna snorted and said contemptuously: “Pharaoh! He wants to take money both here and there…”

Gradually, everyone dispersed from the room. The house was dark. The half-faded sedge smelled sweetly. Silence.

III

Until dinner, which is served at six in the evening, time drags on endlessly and intolerably monotonously. And generally, this daytime interval is the heaviest and emptiest in the life of the house. In mood, it remotely resembles those sluggish, empty hours experienced during big holidays in institutes and other closed women’s establishments, when friends have gone away, when there’s much freedom and much idleness, and a bright, sweet boredom reigns all day long. In only their petticoats and white chemises, with bare arms, sometimes barefoot, the women aimlessly wander from room to room, all unwashed, uncombed, lazily poking an index finger at the keys of an old piano, lazily laying out fortunes with cards, lazily bickering, and with tiresome irritation awaiting the evening.

After breakfast, Lyubka brought Amur the leftover bread and ham trimmings, but she soon grew tired of the dog. Together with Nyura, she bought barberry candies and sunflower seeds, and both now stand behind the fence separating the house from the street, gnawing seeds, the shells of which remain on their chins and chests, and indifferently gossiping about everyone who passes by on the street: about the lamplighter pouring kerosene into the street lamps, about the district policeman with his delivery book under his arm, about the housekeeper from another establishment, scurrying across the road to the general store…

Nyura is a small, goggle-eyed, blue-eyed girl; she has white, flaxen hair, and blue veins on her temples. In her face, there’s something dull and innocent, reminiscent of a white Easter sugar lamb. She is lively, fidgety, curious, meddling in everything, agreeing with everyone, the first to know all the news, and when she speaks, she speaks so much and so quickly that spray flies from her mouth and bubbles foam on her red lips, like a child’s.

Opposite, from the pub, a curly-haired, worn-out, wall-eyed young man, a servant, pops out for a moment and runs to the neighboring tavern.

“Prokhor Ivanovich, hey Prokhor Ivanovich,” Nyura shouts, “would you like some sunflower seeds? I’ll treat you!”

“Come visit us!” Lyuba chimed in.

Nyura snorts and adds through her choking laughter: “For warm feet!”

But the front door opens, and the formidable and strict figure of the senior housekeeper appears in it.

“Pfooey! What is this disgrace?” she shouts imperiously. “How many times do I have to tell you that you can’t run out into the street during the day and furthermore — pfooey! — in just your underwear. I don’t understand how you have no conscience. Decent girls who respect themselves shouldn’t behave so publicly. Thank goodness, you’re not in a soldiers’ establishment, but in a respectable house. Not on Small Yamskaya.”

The girls return to the house, make their way to the kitchen, and sit there on stools for a long time, contemplating the angry cook Praskovya, swinging their legs, and silently gnawing seeds.

In the room of Little Manka, also called Manka the Rowdy and Blondie Manka, a whole company had gathered. Sitting on the edge of the bed, she and another girl, Zoya, a tall, beautiful girl with round eyebrows, prominent gray eyes, and the most typical white, kind face of a Russian prostitute, are playing cards, “Sixty-Six.” Little Manka’s closest friend, Zhenya, lies on her back on the bed behind them, reading a tattered book, “The Queen’s Necklace,” by Mr. Dumas, and smoking. She is the only avid reader in the entire establishment and reads voraciously and indiscriminately. But, contrary to expectation, her intense reading of adventure novels didn’t make her sentimental or soften her imagination at all. Most of all, she liked the long, intricately conceived and cleverly unraveled plot, the magnificent duels in which the viscount untied the bows on his shoes as a sign that he intended not to retreat a single step from his position, and after which the marquis, having run the count through, apologized for making a hole in his beautiful new doublet; the purses filled with gold, carelessly strewn left and right by the main characters, the love affairs and witticisms of Henry IV — in short, all that spicy, gold-and-lace heroism of past centuries of French history. In everyday life, on the contrary, she was sober-minded, sarcastic, practical, and cynically evil. In relation to the other girls in the establishment, she occupied the same place that in closed educational institutions belongs to the strongest, the repeating student, the most beautiful girl in the class — tyrannizing and adored. She was a tall, thin brunette, with beautiful brown, burning eyes, a small proud mouth, a mustache on her upper lip, and a swarthy, unhealthy blush on her cheeks.

Without taking the cigarette out of her mouth and squinting from the smoke, she kept turning pages with a moistened finger. Her legs were bare to the knees, her huge feet of the most vulgar shape: below her big toes, sharp, ugly, irregular bunions protruded sharply outwards.

Here, too, sitting with one leg crossed over the other, slightly bent, with embroidery in her hands, was Tamara, a quiet, cozy, pretty girl, slightly reddish, with that dark and shimmering shade of hair that a fox has on its back in winter. Her real name was Glikeriya, or Lukerya in common parlance. But it was an old custom of houses of tolerance to replace coarse names like Matryona, Agafya, Sykletiniya with sonorous, predominantly exotic names. Tamara was once a nun, or perhaps only a novice in a monastery, and even now her face retained a pale puffiness and timidity, a modest and sly expression characteristic of young nuns. She kept to herself in the house, made no friends, confided in no one about her past life. But, besides her monastic life, she must have had many other adventures: there was something mysterious, silent, and criminal in her unhurried conversation, in the elusive glance of her thick and dark-golden eyes from beneath long, lowered eyelashes, in her manners, smiles, and the intonations of a modest but depraved holy woman. Once, it happened that the girls heard, almost with reverent horror, that Tamara could speak fluent French and German. There was some inner, restrained strength in her. Despite her outward meekness and compliance, everyone in the establishment treated her with respect and caution: the proprietress, her friends, both housekeepers, and even the doorman, that true sultan of the house of tolerance, the universal terror and hero.

“Covered,” said Zoya, and turned over a trump card lying face up under the deck. “I go out with forty, lead with the ace of spades, please, Manyechka, a ten. Finished. Fifty-seven, eleven, sixty-eight. How many do you have?”

“Thirty,” Manka said in an offended voice, pouting her lips, “Well, it’s easy for you, you remember all the moves. Deal… So, what next, Tamarochka?” she turned to her friend. “You speak, I’m listening.”

Zoya shuffled the old, black, greasy cards and let Manya cut, then dealt, first spitting on her fingers.

Tamara, meanwhile, told Manya in a quiet voice, without looking up from her embroidery.

“We embroidered with satin stitch, with gold, altar cloths, aers, archbishop’s vestments… with herbs, flowers, crosses. In winter, you’d sit by the window — the windows were small, with grilles — not much light, smelled of oil, incense, cypress, couldn’t talk: Mother Superior was strict. Someone would hum a Lenten irmos from boredom… ‘Hearken, heaven, and I will speak and sing…’ They sang well, beautifully, and such a quiet life, and such a wonderful smell, snow outside the window, just like a dream…”

Zhenya let the tattered novel drop onto her stomach, tossed her cigarette over Zoya’s head, and said mockingly: “We know your quiet life. You threw infants into latrines. The cunning one always lurks around your holy places.”

“Forty announced. I had forty-six! Finished!” Little Manka exclaimed excitedly and clapped her hands. “I open three.”

Tamara, smiling at Zhenya’s words, replied with a barely perceptible smile that hardly stretched her lips but made small, sly, ambiguous indentations at their corners, just like the Mona Lisa in Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait.

“People tell many tales about nuns… Well, if there was sin…”

“If you don’t sin, you won’t repent,” Zoya interjected seriously and wet her finger in her mouth.

“You sit, embroidering, gold shimmering in your eyes, and from morning standing, your back aches like this, and your legs ache. And in the evening, service again. You knock on Mother Superior’s cell: ‘Through the prayers of our holy fathers, Lord have mercy on us.’ And Mother Superior would answer from the cell in a bass voice: ‘Amen.'”

Zhenya looked at her intently for a while, shook her head, and said meaningfully: “You are a strange girl, Tamara. I look at you and wonder. Well, I understand that these fools, like Sonya, mess around with love. That’s why they’re fools. But you, it seems, have been baked in all the ashes, washed in all the lyes, and yet you also allow yourself such foolishness. Why are you embroidering this shirt?”

Tamara unhurriedly repositioned the fabric more comfortably on her knee with a pin, smoothed the seam with a thimble, and said, without raising her squinted eyes, her head tilted slightly to the side: “I need to do something. It’s so boring. I don’t play cards and don’t like it.”

Zhenya continued to shake her head.

“No, you’re a strange girl, truly strange. You always get more from guests than all of us. Fool, instead of saving money, what do you spend it on? You buy perfume for seven rubles a bottle. Who needs that? Now you’ve bought fifteen rubles worth of silk. Is that for your Senka?”

“Of course, for Senyachka.”

“You found a treasure, too. A wretched thief. He comes to the establishment like some commander. How is it he doesn’t beat you? Thieves, they like that. And he robs you, doesn’t he?”

“I won’t give him more than I want,” Tamara replied meekly and bit off a thread.

“That’s what I wonder about. With your mind, with your beauty, I would have reeled in such a guest that he would take me on as his kept woman. And I’d have my own horses and diamonds.”

“To each their own, Zhenechka. You, too, are a pretty and sweet girl, and your character is so independent and brave, yet here we are, stuck with Anna Markovna.”

Zhenya flared up and replied with unfeigned bitterness: “Yes! Indeed! You’re lucky!… You get all the best guests. You do what you want with them, while all of mine are either old men or suckling infants. I’m unlucky. Some are snotty, others are greenhorns. Most of all, I don’t like the boys. The little bastard comes, he’s scared, rushes, trembles, and once he’s done his business, he doesn’t know where to put his eyes from shame. He’s contorted with disgust. I’d just want to punch him in the face. Before giving a ruble, he holds it in his fist in his pocket, the whole ruble is hot, even sweaty. Mama’s boy! His mother gives him a grivennik for a French bun with sausage, and he saved it for a girl. The other day I had a cadet. So I purposely, just to spite him, said: ‘Here, darling, here are some caramels for the road, you can suck on them on your way back to the corps.’ He was offended at first, but then he took them. I deliberately peeked from the porch afterwards: when he went out, he looked back, and immediately put the caramel in his mouth. Pig!”

“Well, old men are even worse,” Little Manka said in a tender voice and slyly glanced at Zoya, “What do you think, Zoyenka?”

Zoya, who had finished playing and was just about to yawn, now couldn’t manage to yawn. She wanted to either be angry or laugh. She had a regular guest, some high-ranking old man with perverted erotic habits. The entire establishment made fun of his visits to her.

Zoya finally managed to yawn.

“To hell with you all,” she said in a hoarse, post-yawn voice, “damn him, the old anathema!”

“But still, the worst of all,” Zhenya continued to muse, “worse than your director, Zoyenka, worse than my cadet, worst of all — are your lovers. What’s so joyful about it: he comes drunk, acts up, mocks, wants to portray something, but nothing comes of it. Please tell me: a little boy. A brute, dirty, beaten, smelly, his whole body covered in scars, only one thing to praise him for: the silk shirt Tamarochka will embroider for him. He swears, the son of a bitch, obscenely, tries to fight. Ptooey! No,” she suddenly exclaimed in a cheerful, defiant voice, “whom I truly and sincerely love, forever and ever, is my Manyechka, Blondie Manka, Little Manka, my Manka the Rowdy.”

And unexpectedly, embracing Manya by the shoulders and chest, she pulled her close, threw her onto the bed, and began to kiss her hair, eyes, and lips long and hard. Manka struggled to break free from her, her light, thin, fluffy hair disheveled, her face all rosy from the struggle, and her eyes downcast, wet with shame and laughter.

“Leave me, Zhenechka, leave me. Oh, really… Let go!”

Little Manya is the meekest and quietest girl in the entire establishment. She is kind, compliant, can never refuse anyone a request, and everyone instinctively treats her with great tenderness. She blushes at every trifle and at such times becomes especially attractive, as very delicate blondes with sensitive skin can be attractive. But let her drink three or four shots of Benedictine liqueur, which she loves very much, and she becomes unrecognizable and creates such scandals that the intervention of the housekeepers, the doorman, and sometimes even the police is always required. It costs her nothing to hit a guest in the face or throw a glass full of wine in his eyes, overturn a lamp, or insult the proprietress. Zhenya treats her with some strange, tender patronage and rough adoration.

“Young ladies, dinner! Dinner, young ladies!” shouted Zosya the housekeeper, running down the corridor. On the run, she opened the door to Manya’s room and hastily threw in:

“Dinner, dinner, young ladies!”

They went back to the kitchen, still in their underwear, all unwashed, in slippers and barefoot. They served delicious borscht with pork rind and tomatoes, cutlets, and a pastry: tubes with cream filling. But no one had much appetite due to their sedentary life and irregular sleep, and also because most of the girls, like institute girls on a holiday, had already sent to the shop during the day for halva, nuts, rahat-lukum, pickled cucumbers, and taffy, thus spoiling their appetites. Only Nina, a small, snub-nosed, nasal country girl, seduced by some traveling salesman only two months ago and then sold by him to the brothel, ate for four. She still retained the excessive, hoarding appetite of a commoner.

Zhenya, who had only daintily picked at a cutlet and eaten half a cream tube, said to her with a tone of feigned sympathy: “You should eat my cutlet too, Feklusha. Eat, dear, eat, don’t be shy, you need to gain weight. And you know what, girls,” she addressed her friends, “our Feklusha has a tapeworm, and when a person has a tapeworm, they always eat for two: half for themselves, half for the worm.”

Nina sniffed angrily and replied in a bass voice, unexpected for her size, and through her nose: “I don’t have any worms. You have worms, that’s why you’re so thin.”

And she calmly continued to eat, and after dinner felt sleepy as a boa constrictor, burped loudly, drank water, hiccupped, and secretly, if no one was looking, crossed her mouth out of old habit.

But now, in the corridors and rooms, Zosya’s clear voice was heard:

“Dress up, young ladies, dress up. No time to lounge around… To work…”

A few minutes later, all the rooms in the establishment smelled of burnt hair, borothymol soap, and cheap cologne. The girls were dressing for the evening.

IV

Late dusk set in, followed by a warm, dark night, but a thick crimson sunset still glowed long, until midnight. Semyon, the doorman of the establishment, lit all the lamps on the hall walls and the chandelier, as well as the red lantern above the porch. Semyon was a lean, stooping, silent and stern man, with broad, straight shoulders, a brunette, pockmarked, with eyebrows and a mustache thinned by smallpox, and with black, dull, insolent eyes. During the day he was free and slept, and at night he sat continuously in the entrance hall under the reflector to help guests with their coats and to be ready in case of any disturbance.

The pianist arrived — a tall, fair-haired, delicate young man with a walleye in his right eye. While there were no guests, he and Isay Savvich quietly rehearsed the “pas d’Espagne” — a dance that was beginning to come into fashion at the time. For each dance ordered by guests, they received thirty kopecks for a light dance and fifty kopecks for a quadrille. But half of this price was taken by the proprietress, Anna Markovna, and the other half the musicians divided equally. Thus, the pianist received only a quarter of the total earnings, which, of course, was unfair, because Isay Savvich was self-taught and had a wooden ear. The pianist constantly had to coach him on new melodies, correct him, and drown out his mistakes with loud chords. The girls told guests with some pride about the pianist, that he had been at the conservatory and was always the top student, but since he was Jewish and moreover suffered from an eye disease, he could not finish the course. They all treated him very carefully and attentively, with a sympathetic, somewhat cloying pity, which very much ties in with the internal, behind-the-scenes morals of houses of tolerance, where beneath the outward rudeness and the swagger of obscene words lives the same sugary, hysterical sentimentality as in girls’ boarding schools and, they say, in penal prisons.

Everyone was already dressed and ready to receive guests in Anna Markovna’s house and languished in idleness and anticipation. Despite the fact that most of the women felt complete, even somewhat squeamish indifference towards men, with the exception of their lovers, vague hopes still stirred and came alive in their souls before each evening: who would choose them, would something unusual, funny, or exciting happen, would a guest surprise them with their generosity, would there be some miracle that would turn their whole life upside down? In these premonitions and hopes there was something similar to the excitement experienced by a habitual gambler counting his cash before heading to the club. Furthermore, despite their lack of a sexual desire, they had still not lost the most important, instinctive desire of women — to please.

And indeed, sometimes quite bizarre individuals would come to the house and various tumultuous, motley events would occur. Suddenly, the police would appear with plainclothes detectives and arrest some respectable-looking, irreproachable gentlemen and lead them away, pushing them by the neck. Sometimes fights would break out between a drunk, rowdy company and the doormen from all the establishments, who would rush to help their fellow doorman — a fight during which windowpanes and piano soundboards would shatter, when the legs of plush chairs would be ripped off as weapons, blood would flood the parquet in the hall and the steps of the staircase, and people with punctured sides and broken heads would fall into the mud at the entrance, to the bestial, greedy delight of Zhenka, who, with glowing eyes and happy laughter, would plunge into the thick of the fray, slapping her thighs, swearing and inciting, while her friends shrieked in fear and hid under the beds.

It happened that some artel foreman or cashier would arrive with a retinue of hangers-on, long gone astray in multi-thousand ruble embezzlement, card games, and disgraceful carousing, and now, before suicide or the defendant’s bench, would squander his last money in a drunken, absurd stupor. Then the doors and windows of the house would be tightly locked, and for two days straight a nightmarish, boring, wild Russian orgy would ensue, with shouts and tears, with desecration of the female body; paradisiacal nights would be arranged, during which drunken, bow-legged, hairy, pot-bellied men and women with flabby, yellow, sagging, flimsy bodies would grotesquely contort naked to the music, drinking and devouring like pigs in beds and on the floor, amidst a stuffy, alcohol-soaked atmosphere, polluted by human breath and the effluvia of unclean skin.

Occasionally, a circus athlete would appear in the establishment, making a strangely cumbersome impression in the low-ceilinged rooms, like a horse brought into a room; a Chinese man in a blue jacket, white stockings and with a queue; a black man from a café-chantant in a tuxedo and plaid trousers, with a flower in his buttonhole and starched linen which, to the girls’ surprise, not only did not get dirty from his black skin, but seemed even more dazzlingly bright.

These rare individuals stirred the jaded imagination of the prostitutes, aroused their exhausted sensuality and professional curiosity, and all of them, almost in love, would follow them, jealous and snapping at each other.

There was a case when Semyon let some elderly man, dressed in a bourgeois manner, into the hall. There was nothing special about him: a stern, thin face with prominent, hard, malevolent cheekbones like knots, a low forehead, a wedge-shaped beard, thick eyebrows, one eye noticeably higher than the other. Upon entering, he raised his fingers, folded for a cross, to his forehead, but after searching the corners with his eyes and finding no icon, he was not at all embarrassed, lowered his hand, spat, and immediately approached the plumpest girl in the entire establishment — Katka — with a businesslike air.

“Let’s go!” he commanded curtly and decisively nodded his head towards the door.

But during his absence, the all-knowing Semyon, with a mysterious and even somewhat proud look, managed to inform his then-mistress Nyura, and she, in a whisper, with horror in her widened eyes, secretly told her friends that the bourgeois man’s surname was Dyadchenko and that last autumn, in the absence of an executioner, he had volunteered to carry out the execution of eleven rebels and personally hanged them in two mornings. And — monstrous as it may seem — at that hour there was not a single girl in the entire establishment who did not feel envy for the plump Katka and did not experience a creepy, tart, dizzying curiosity. When Dyadchenko left half an hour later with his dignified and stern demeanor, all the women silently, mouths agape, watched him to the exit door and then followed him from the windows as he walked down the street. Then they rushed into Katka’s room, where she was dressing, and showered her with questions. They looked with a new feeling, almost with astonishment, at her bare, red, plump hands, at the still crumpled bed, at the old, grimy paper ruble that Katka showed them, taking it out of her stocking. Katka couldn’t tell them anything — “a man like any man, like all men,” she said with calm perplexity — but when she found out who her guest had been, she suddenly burst into tears, not knowing why herself.

This man, out of all outcasts, who had fallen as low as human imagination can conceive, this voluntary executioner, treated her without rudeness, but with such an absence of even a hint of tenderness, with such contempt and wooden indifference, as one treats not a human being, not even a dog or a horse, and not even an umbrella, a coat, or a hat, but as some dirty object for which there is a momentary, unavoidable need, but which, once that need is past, becomes alien, useless, and disgusting. The plump Katka could not grasp the full horror of this thought with her turkey-fed brain and therefore cried — as it seemed even to her — unreasoningly and senselessly.

There were other occurrences that agitated the murky, dirty lives of these poor, sick, foolish, unfortunate women. There were cases of wild, unrestrained jealousy with revolver shots and poisoning; sometimes, very rarely, tender, ardent, and pure love blossomed on this manure; sometimes women even left the establishment with the help of a loved one, but almost always returned. Two or three times it happened that a woman from the brothel suddenly found herself pregnant, and this always appeared, outwardly, funny and shameful, but in the depths of the event — touching.

And no matter what, every evening brought with it such an irritating, tense, spicy anticipation of adventures that any other life, after the house of tolerance, seemed bland and boring to these lazy, spineless women.

V

The windows were thrown wide open to the fragrant darkness of the evening, and the tulle curtains swayed gently back and forth with the imperceptible movement of the air. It smelled of dewy grass from the stunted little front garden before the house, a little of lilac, and of wilting birch leaves from the Trinity trees at the entrance. Lyuba, in a blue velvet blouse with a low-cut neckline, and Nyura, dressed like a “bébé” in a loose pink sack dress to her knees, with her fair hair unbound and curls on her forehead, lay embracing on the windowsill and quietly sang a very well-known topical song among prostitutes about a hospital. Nyura sang the first voice thinly, through her nose, and Lyuba echoed her with a somewhat muffled alto:

Monday is coming,

It’s time for me to be discharged,

Doctor Krasov won’t let me go…

In all the houses, the open windows were brightly lit, and hanging lanterns burned before the entrances. Both girls could clearly see the interior of the hall in Sofya Vasilyevna’s establishment opposite: the shiny yellow parquet, the dark-cherry drapes on the doors, caught with cords, the end of a black grand piano, a pier glass in a gilded frame, and women’s figures in opulent dresses, now flashing in the windows, now disappearing, and their reflections in the mirrors. Treppel’s carved porch, to the right, was brightly illuminated by bluish electric light from a large frosted globe.

The evening was quiet and warm. Somewhere far, far away, beyond the railway line, beyond some black roofs and thin black tree trunks, low over the dark earth, which the eye could not see but seemed to feel the mighty green spring tone, a narrow, long strip of late twilight glowed crimson gold, cutting through the bluish haze. And in this vague distant light, in the gentle air, in the smells of the approaching night, there was a secret, sweet, conscious sadness, which is so tender on evenings between spring and summer. The vague hum of the city floated, the bored, nasal drone of an accordion was heard, the lowing of cows, someone’s soles scuffed dryly, and a iron-shod stick clacked loudly against the pavement slabs, lazily and erratically rattled the wheels of a cabriolet, rolling at a walk along the street, and all these sounds wove beautifully and softly into the thoughtful slumber of the evening. And the whistles of locomotives on the railway line, marked in the darkness by green and red lights, sounded with quiet, melodious caution.

Here comes the nurse,

Bringing a sugar bun…

Bringing a sugar bun,

Distributes it equally to everyone.

“Prokhor Ivanovich!” Nyura suddenly called out to the curly-haired servant from the pub, who was darting across the road like a light black silhouette. “Hey, Prokhor Ivanych!”

“Oh, you all!” he snapped hoarsely. “What now?”

“A friend of yours told me to say hello. I saw him today.”

“What friend?”

“Such a handsome one! A charming brunette… No, you’d better ask where I saw him?”

“Well, where?” Prokhor Ivanovich paused for a minute.

“Here’s where: on our nail, on the fifth shelf, where the dead wolves are.”

“Bah! You silly fool.”

Nyura shrieked with laughter across the entire area and collapsed onto the windowsill, kicking her legs in high black stockings. Then, stopping her laughter, she immediately made wide, surprised eyes and said in a whisper: “And you know, girl, he cut a woman the year before last, Prokhor did. I swear to God.”

“Really? To death?”

“No, not to death. She recovered,” Nyura said, as if with regret. “But she lay in Alexandrovskaya for two months. The doctors said that if it had been just a tiny bit higher,” — she indicated with her finger — “it would have been all over. Finis!”

“Why did he do it to her?”

“How should I know? Maybe she hid money from him or cheated. He was her lover — a beast.”

“And what happened to him for that?”

“Nothing. There was no evidence. There was a general brawl. About a hundred people were fighting. She also told the police she had no suspicions. But Prokhor himself later boasted: ‘That time I didn’t cut Dunka, but I’ll finish her off another time,’ he said. ‘She won’t escape my hands. It’ll be all over for her!'”

Lyuba shivered all over her back.

“They’re desperate, these beasts!” she said quietly, with horror in her voice.

“Terribly so! You know, I had an affair with our Semyon for a whole year. Such a brute, a scoundrel! There wasn’t a living spot on me, I walked around all bruised. And not for any reason, but just like that, he’d come into my room in the morning, lock himself in, and start tormenting me. He’d twist my arms, pinch my breasts, start choking me. Or he’d kiss and kiss, then bite my lips so hard that blood would even spurt… I’d cry, and all he needed was that. He’d lunge at me like an animal, even tremble. And he took all my money, every single kopeck. I couldn’t even buy ten cigarettes. He’s stingy, Semyon is, he puts everything in his savings book… He says that when he saves a thousand rubles, he’ll go to a monastery.”

“Really?”

“I swear to God. You can look in his room: all day long, day and night, a small lamp burns before the icons. He’s very devout… Only I think he’s like that because he has heavy sins on him. He’s a murderer.”

“What are you saying?”

“Oh, forget him, let’s stop talking about him, Lyubochka. Well, let’s continue:”

I’ll go to the pharmacy, I’ll buy poison,

I’ll poison myself —

Nyura sang in a thin voice.

Zhenya walked back and forth in the hall, hands on her hips, swaying as she moved and looking at herself in all the mirrors. She wore a short, orange satin dress with straight, deep folds on the skirt, which swayed rhythmically left and right with the movement of her hips. Little Manka, an ardent card player, ready to play from morning till morning without stopping, was pouting in “Sixty-Six” with Pasha, both women having left an empty chair between them for convenient dealing, and collecting their tricks in their skirts, spread out between their knees. Manka wore a brown, very modest dress, with a black apron and a pleated black bib; this costume suited her delicate blond head and small stature very well, making her look younger and resembling a penultimate-year gymnasium student.

Her partner Pasha was a very strange and unfortunate girl. She should have been not in a house of tolerance for a long time, but in a psychiatric hospital because of a tormenting nervous ailment that made her feverishly, with morbid greed, give herself to every man, even the most repulsive, who would choose her. Her friends mocked her and somewhat despised her for this vice, just as for some betrayal of corporate enmity towards men. Nyura imitated her sighs, moans, shouts, and passionate words very accurately, which she could never hold back in moments of ecstasy and which could be heard through two or three partitions in neighboring rooms. Rumor had it about Pasha that she had not entered the brothel out of need, or through seduction or deception, but had entered it herself, voluntarily, following her terrible insatiable instinct. But the mistress of the house and both housekeepers pampered Pasha in every way and encouraged her insane weakness, because thanks to it, Pasha was in great demand and earned four, five times more than any of the other girls — she earned so much that on busy holidays she was not brought out to “more ordinary” guests at all, or they were refused under the pretext of Pasha’s illness, because regular good guests would be offended if they were told that their familiar girl was busy with another. And Pasha had a multitude of such regular guests; many were completely sincerely, though brutishly, in love with her, and not so long ago two almost simultaneously invited her to be their kept woman: a Georgian — a clerk from a Kakhetian wine shop — and some railway agent, a very proud and very poor nobleman of tall stature, with terry cuffs, with an eye replaced by a black circle on an elastic band. Pasha, passive in everything except her impersonal voluptuousness, would, of course, have gone with anyone who called her, but the house administration zealously guarded its interests in her. Approaching madness already showed in her pretty face, in her half-closed eyes, always smiling with a kind of intoxicated, blissful, meek, shy, and indecent smile, in her languid, softened, wet lips that she constantly licked, in her short, quiet laughter — the laughter of an idiot. And at the same time, this true victim of public temperament was in everyday life very good-natured, compliant, a complete altruist, and was very ashamed of her excessive passion. She was tender with her friends, loved to kiss and hug them and sleep in the same bed, but everyone seemed to be a little squeamish of her.

“Manyechka, darling, my sweet,” Pasha said tenderly, touching Manya’s hand, “tell my fortune, my golden little one.”

“N-no,” Manya pouted her lips, like a child. “Let’s play more.”

“Manyechka, pretty one, lovely one, my treasure, my dear, my precious…”

Manya yielded and laid out the deck on her knees. A heart suit came up, a small monetary interest, and a meeting in a spade house with a club king.

Pasha clapped her hands joyfully: “Ah, it’s my Levanchik! Yes, he promised to come today. Of course, Levanchik.”

“Is that your Georgian?”

“Yes, yes, my little Georgian. Oh, how pleasant he is. I’d never let him go. You know what he told me last time? ‘If you live in a public house any longer, I will make myself die and you die too.’ And he flashed his eyes at me like that.”

Zhenya, who had stopped nearby, listened to her words and asked haughtily: “Who said that?”

“My Georgian Levanchik. Both you die and I die.”

“Fool. He’s not a Georgian, he’s just an Armenian. You crazy fool.”

“No, he’s Georgian. And it’s quite strange of you…”

“I tell you — Armenian. I know better. Fool!”

“Why are you swearing, Zhenya? I didn’t swear at you first.”

“As if you would swear first. Fool! Does it matter to you who he is? Are you in love with him, or what?”

“Yes, I am in love!”

“Well, then you’re a fool. And are you in love with that one, with the cockade, the cross-eyed one, too?”

“So what? I respect him very much. He’s very respectable.”

“And with Kolka the accountant? And with the contractor? And with Antoshka-potato? And with the fat actor? Ugh, shameless hussy!” Zhenya suddenly shrieked. “I can’t look at you without disgust. You bitch! If I were as wretched as you, I’d rather take my own life, hang myself with a corset lace. You snake!”

Pasha silently lowered her eyelashes over her tear-filled eyes. Manya tried to stand up for her.

“Why are you like this, Zhenechka… Why are you so hard on her…”

“Oh, you’re all alike!” Zhenya sharply cut her off. “No self-respect!… Some boor comes, buys you like a piece of beef, hires you like a cabman, by the meter, for an hour of love, and you just melt: ‘Oh, my lover! Oh, unearthly passion!’ Ptooey!”

She angrily turned her back on them and continued her diagonal stroll across the hall, swaying her hips and squinting at herself in every mirror.

At this time, Isaac Davidovich, the pianist, was still struggling with the unyielding violinist.

“Not like that, not like that, Isay Savvich. Put down the violin for a minute. Listen to me a little. Here’s the melody.”

He played with one finger and hummed in that terrible, goat-like voice that all Kapellmeisters, which he once prepared for, possess:

“Es-tam, es-tam, zs-ti-am-ti-am. Now repeat after me the first knee for the first time… Well… ein, zwei…”

Their rehearsal was being closely watched by: gray-eyed, round-faced, round-browed, ruthlessly plastered with cheap blush and powder Zoya, who leaned on the piano, and Vera, thin, with a worn face, in a jockey costume: in a round cap with a straight brim, in a silk striped, blue and white, jacket, in white, tightly fitted breeches and in patent leather boots with yellow cuffs. Vera indeed looked like a jockey, with her narrow face, on which very shiny blue eyes, beneath a dashing fringe pulled down onto her forehead, were set too close to her hooked, nervous, very beautiful nose. When, finally, after long efforts, the musicians got in sync, short Vera approached tall Zoya with that small, constrained gait, with her bottom sticking out and elbows held out, the way only women in men’s costumes walk, and gave her, spreading her arms wide downwards, a comical masculine bow. And they began to dash around the hall with great pleasure.

Nimble Nyura, always the first to announce all news, suddenly jumped from the windowsill and shouted, choking with excitement and haste:

“To Treppel’s… a cab… with electricity… Oh, girls… I could die on the spot… electricity on the shafts!”

All the girls, except for proud Zhenya, leaned out of the windows. Indeed, a cab was standing near Treppel’s entrance. Its brand-new, fancy cabriolet gleamed with fresh varnish, two tiny electric lanterns glowed yellow on the ends of the shafts, a tall white horse impatiently shook its beautiful head with a bare pink spot on its muzzle, pawed the ground, and pricked its thin ears; the bearded, stout coachman himself sat on the box, like a statue, his arms stretched straight along his knees.

“Oh, I wish I could ride!” Nyura shrieked. “Uncle cabman, hey uncle cabman,” she shouted, leaning over the windowsill, “give a poor little girl a ride… Give me a ride for love…”

But the cabman laughed, made a barely noticeable movement with his fingers, and the white horse immediately, as if it had been waiting for just that, started off at a good trot, turned beautifully back, and floated with measured speed into the darkness with the cabriolet and the coachman’s broad back.

“Phooey! Disgrace!” Emma Eduardovna’s indignant voice rang out in the room. “Well, where is it ever seen that respectable young ladies allow themselves to lean out of the window and shout across the entire street. Oh, scandal! And it’s always Nyura, and always that terrible Nyura!”

She was majestic in her black dress, with a yellow, flabby face, with dark bags under her eyes, with three dangling, trembling chins. The girls, like misbehaving boarding school students, primly seated themselves on chairs along the walls, except for Zhenya, who continued to contemplate herself in all the mirrors. Two more cabmen drove up opposite, to Sofya Vasilyevna’s house. The area began to liven up. Finally, another cabriolet rattled over the cobblestones, and its noise suddenly stopped at Anna Markovna’s entrance.

Semyon the doorman was helping someone get undressed in the anteroom. Zhenya peeked in, holding onto the doorframes with both hands, but immediately turned back and shrugged her shoulders on the go, shaking her head negatively.

“I don’t know, some complete stranger,” she said in a low voice. “Never been here before. Some old man, fat, in gold spectacles and in a uniform.”

Emma Eduardovna commanded in a voice that sounded like a cavalry bugle call:

“Young ladies, to the hall! To the hall, young ladies!”

One by one, with haughty gaits, they entered the hall: Tamara with bare white arms and a naked neck adorned with a string of artificial pearls, plump Katka with a fleshy, square face and a low forehead — she was also décolleté, but her skin was red and bumpy; the new girl Nina, snub-nosed and clumsy, in a parrot-green dress; another Manka — Big Manka or Manka the Crocodile, as she was called, and — lastly — Sonya the Rudder, a Jewish girl, with an ugly dark face and an extremely large nose, from which she got her nickname, but with such beautiful large eyes, simultaneously meek and sad, burning and moist, as are found among women throughout the world only among Jewish women.

VI

The elderly guest, in the uniform of a charitable institution, entered with slow, hesitant steps, leaning his body slightly forward with each step and rubbing his palms in circular motions, as if washing them. Since all the women remained solemnly silent, as if not noticing him, he crossed the hall and sat down on a chair next to Lyuba, who, according to etiquette, merely gathered her skirt slightly, maintaining the distracted and independent air of a girl from a respectable house.

“Hello, young lady,” he said.

“Hello,” Lyuba replied curtly.

“How are you?”

“Fine, thank you. Offer me a cigarette.”

“Excuse me — I don’t smoke.”

“Well, well. A man who doesn’t smoke. Then offer me some Lafite with lemonade. I terribly love Lafite with lemonade.”

He remained silent.

“Oh, what a stingy fellow, old man! Where do you work? Are you a civil servant?”

“No, I’m a teacher. I teach German.”

“But I’ve seen you somewhere, daddy. Your face is familiar. Where did I meet you?”

“Well, I really don’t know. On the street, perhaps.”

“Maybe on the street… At least offer me an orange. Can I ask for an orange?”

He again fell silent, looking around. His face glistened, and the pimples on his forehead turned red. He slowly assessed all the women, choosing a suitable one for himself, and at the same time feeling embarrassed by his silence. There was nothing to talk about; moreover, Lyuba’s indifferent importunity annoyed him. He liked plump Katya for her large, cow-like body, but, he decided in his mind, she must be very cold in love, like all full women, and besides, she was not beautiful in the face. Vera also aroused him with her boyish appearance and strong thighs, tightly embraced by white tights, and fair Manka, so similar to an innocent gymnasium student, and Zhenya with her energetic, dark-skinned, beautiful face. For a moment he almost settled on Zhenya, but he only twitched in his chair and did not dare: from her unconstrained, unapproachable, and careless demeanor, and from how she sincerely paid him no attention, he guessed that she was the most spoiled among all the girls in the establishment, accustomed to visitors spending more on her than on others. And the teacher was a calculating man, burdened by a large family and an exhausted, twisted wife, whose demands had worn her out and who suffered from many female ailments. Teaching in a girls’ gymnasium and institute, he constantly lived in a kind of secret voluptuous delirium, and only German restraint, stinginess, and cowardice helped him keep his eternally aroused lust in check. But two or three times a year, with incredible deprivation, he would carve out five or ten rubles from his beggarly budget, denying himself his favorite evening mug of beer and saving on horsecars, for which he had to walk long distances across the city on foot. He set aside this money for women and spent it slowly, with relish, trying to prolong and cheapen the pleasure as much as possible. And for his money he wanted a great deal, almost the impossible: his German sentimental soul vaguely yearned for innocence, shyness, poetry in the blonde image of Gretchen, but, as a man, he dreamed, wished, and demanded that his caresses bring the woman into ecstasy, and trembling, and sweet exhaustion.

However, all men sought the same — even the most wretched, ugly, crooked, and impotent among them — and ancient experience had long taught women to imitate the most fervent passion with voice and movements, maintaining complete composure during tumultuous moments.

“At least order the musicians to play a polka. Let the young ladies dance,” Lyuba grumbled.

This suited him well. To decide to get up and lead one of the girls out of the hall under the cover of music, amidst the bustle of dances, was much more convenient than doing it amidst general silence and stiff immobility.

“How much does that cost?” he asked cautiously.

“A quadrille is fifty kopecks, and dances like these are thirty kopecks. Is that alright?”

“Well then… please… I don’t mind…” he agreed, pretending to be generous. “Who should I tell here?”

“Over there, the musicians.”

“Of course… with pleasure… Mr. Musician, please, something from the lighter dances,” he said, placing silver on the piano.

“What do you wish?” Isay Savvich asked, pocketing the money. “A waltz, a polka, a polka-mazurka?”

“Well… something like that…”

“Waltz, waltz!” Vera, a great lover of dancing, shouted from her place.

“No, a polka!… A waltz!… A Hungarian dance!… A waltz!” others demanded.

“Let them play a polka,” Lyuba decided in a capricious tone. “Isay Savvich, please play a polka. This is my husband, and he’s ordering it for me,” she added, embracing the teacher’s neck. “Right, daddy?”

But he freed himself from her arm, drawing his head in like a turtle, and she, without any offense, went to dance with Nyura. Three more pairs were twirling. In their dances, all the girls tried to keep their waists as straight as possible and their heads as still as possible, with complete indifference on their faces, which was one of the conditions of good manners in the establishment. Under the commotion, the teacher approached Manka the Small.

“Shall we go?” he said, offering his arm in a loop.

“Let’s go,” she replied, laughing.

She led him to her room, furnished with all the coquetry of a mid-range brothel bedroom: a dresser covered with a knitted tablecloth, and on it a mirror, a bouquet of paper flowers, several empty bonbonnières, a powder compact, a faded photograph of a fair-haired young man with a proudly surprised face, several business cards; above the bed, covered with a pink piqué blanket, a rug depicting a Turkish sultan lounging in his harem with a hookah in his mouth was nailed along the wall; on the walls, several more photographs of dandyish men of the lackey and actor type; a pink lantern hanging on chains from the ceiling; a round table under a carpet tablecloth, three Viennese chairs, an enameled basin and a matching pitcher in the corner on a stool, behind the bed.

“Treat me, darling, to Lafite with lemonade,” Manka the Small asked, as was customary, unbuttoning her bodice.

“Later,” the teacher replied sternly. “That will depend on you. And besides: what kind of Lafite could you have here? Some kind of swill.”

“We have good Lafite,” the girl retorted, offended. “Two rubles a bottle. But if you’re so stingy, at least buy some beer. Alright?”

“Well, beer, that’s possible.”

“And lemonade and oranges for me. Yes?

“A bottle of lemonade — yes, but no oranges. Later, perhaps, I’ll even treat you to champagne, it will all depend on you. If you try hard.”

“So I’ll ask for four bottles of beer and two lemonades, daddy? Yes? And for me, at least a bar of chocolate. Alright? Yes?”

“Two bottles of beer, a bottle of lemonade, and nothing else. I don’t like to bargain. If it’s necessary, I’ll ask myself.”

“Can I invite a friend?”

“No, please, no friends.”

Manka leaned out the door into the corridor and shouted loudly: “Housekeeper! Two bottles of beer and a bottle of lemonade for me.”

Semyon arrived with a tray and began to uncork the bottles with his usual speed. The housekeeper Zosya followed him.

“Well, now, how nicely settled. With a legal marriage!” she congratulated.

“Daddy, treat the housekeeper to some beer,” Manka asked. “Have some, housekeeper.”

“Well, in that case, to your health, sir. Your face seems familiar to me?”

The German drank beer, sucking and licking his mustache, and impatiently waited for the housekeeper to leave. But she, having put down her glass and thanked him, said:

“Allow me, sir, to collect the money from you. For the beer, as it should be, and for the time. This is better for you and more convenient for us.”

The demand for money disconcerted the teacher, as it completely ruined the sentimental part of his intentions. He became angry:

“What is this, really, such boorishness! It seems I’m not planning to run away from here. And then don’t you know how to discern people? You see that a respectable person, in uniform, has come to you, not some vagrant. What sort of importunity is this!”

The housekeeper relented slightly.

“Don’t be offended, sir. Of course, for the visit you yourself will give the young lady. I think you won’t offend her, she’s a lovely girl of ours. But please pay for the beer and lemonade. I also have to report to the mistress. Two bottles of beer, fifty each — a ruble, and lemonade thirty — a ruble thirty.”

“Good heavens, a bottle of beer for fifty kopecks!” the German exclaimed indignantly. “Why, I can get it for twelve kopecks at any porter-house.”

“Well, then go to a porter-house if it’s cheaper there,” Zosya said, offended. “But if you’ve come to a decent establishment, then this is the official price — fifty kopecks. We don’t take anything extra. This is better. Twenty kopecks change for you?”

“Yes, definitely change,” the teacher firmly emphasized. “And I ask that no one else enter.”

“No, no, no, what are you saying,” Zosya fussed by the door. “Make yourselves comfortable, as you wish, to your full pleasure. Enjoy your stay.”

Manka locked the door behind her with the hook and sat on the German’s knee, embracing him with her bare arm.

“How long have you been here?” he asked, sipping his beer. He felt vaguely that the imitation of love that was about to happen required some spiritual closeness, a more intimate acquaintance, and so, despite his impatience, he began the usual conversation that almost all men have alone with prostitutes, and which makes them lie almost mechanically, lie without distress, enthusiasm, or malice, following a very old pattern.

“Not long, only the third month.”

“And how old are you?”

“Sixteen,” Manka the Small lied, taking five years off her age.

“Oh, so young!” the German said, surprised, and stooped and groaned as he took off his boots. “How did you end up here?”

“Well, an officer deprived me of my innocence there… back home. And my mother is terribly strict. If she found out, she’d strangle me with her own hands. So I ran away from home and came here…”

“And did you love the officer, the first one?”

“If I hadn’t loved him, I wouldn’t have gone with him. He, the scoundrel, promised to marry me, and then he got what he wanted and left.”

“Were you ashamed the first time?”

“Of course, I was ashamed… Do you, daddy, prefer with the light on or off? I’ll dim the lamp a little. Alright?”

“And what about you, don’t you get bored here? What’s your name?”

“Manya. Of course I get bored. What a life we have!”

The German kissed her firmly on the lips and again asked: “And do you like men? Are there men you find pleasant? Do they give you pleasure?”

“Of course there are,” Manka laughed. “I especially like ones like you, nice, plump ones.”

“You like them? Huh? Why do you like them?”

“Oh, I just like them. You’re nice too.”

The German thought for a few seconds, thoughtfully sipping his beer. Then he said what almost every man says to a prostitute in these moments preceding the casual possession of her body:

“You know, Marichen, I like you very much too. I’d gladly take you as my kept woman.”

“You’re married,” she countered, touching his ring.

“Yes, but, you see, I don’t live with my wife, she’s unwell, she can’t fulfill her marital duties.”

“Poor thing! If she found out where you go, daddy, she’d probably cry.”

“Let’s leave that. So, you know, Mari, I’m always looking for a girl like you, such a modest and pretty one. I’m a man of means, I’d find you an apartment with board, heating, lighting. And forty rubles a month for pin money. Would you go?”

“Why not go, I’d go.”

He kissed her passionately, but a secret fear quickly darted through his cowardly heart.

“Are you healthy?” he asked in a hostile, trembling voice.

“Yes, I’m healthy. We have a doctor’s examination every Saturday.”

Five minutes later, she left him, hiding the earned money in her stocking as she walked, money on which, as a first start, she had previously spat, according to superstitious custom. There was no more talk of being kept or of pleasantness. The German remained dissatisfied with Manka’s coldness and ordered the housekeeper to be called to him.

“Housekeeper, my husband wants you!” Manya said, entering the hall and fixing her hair in front of the mirror.

Zosya left, then returned and called Pasha into the corridor. Then she returned to the hall alone.

“What’s this, Manka the Small, you didn’t please your gentleman?” she asked with a laugh. “He’s complaining about you: ‘She’s not a woman, he says, but some wooden log, a piece of ice.'” I sent Pasha to him.

“Ugh, how disgusting!” Manka wrinkled her nose and spat. “He starts talking. Asks: do you feel anything when I kiss you? Do you feel a pleasant excitement? Old dog. He says he’ll take me as his kept woman.”

“They all say that,” Zoya remarked indifferently.

But Zhenya, who had been in a bad mood since morning, suddenly flared up.

“Oh, that boor, that miserable boor!” she exclaimed, blushing and energetically putting her hands on her hips. “I’d take him, the old scoundrel, by the ear, and lead him to the mirror and show him his vile mug. What? Good-looking? And how will you be even better when drool flows from your mouth, and your eyes cross, and you start to choke and wheeze, and snort right in a woman’s face. And you want for your cursed ruble for me to spread out like a pancake before you and for my eyes to pop out from your disgusting love? I’d hit him in the face, the scoundrel, in the face! Till he bled!”

“Oh, Zhenya! Stop it! Phooey!” Emma Eduardovna, who was fastidious and offended by her coarse tone, stopped her.

“I won’t stop!” she sharply cut her off. But she fell silent herself and angrily walked away, with flaring nostrils and fire in her darkened, beautiful eyes.

VII

The hall gradually filled up. Vanka-Vstanka, long familiar to everyone in the Yama — a tall, thin, red-nosed, gray-haired old man in a forest ranger’s uniform, high boots, and a wooden yardstick always sticking out of his side pocket — arrived. He spent whole days and evenings as a regular at the billiard room next to the tavern, perpetually half-drunk, spouting his jokes, rhymes, and sayings, being overly familiar with the doorman, the housekeepers, and the girls. In the houses, everyone — from the madam to the maids — treated him with a casual, slightly disdainful, but not malicious, mockery. Sometimes he wasn’t entirely useless: he’d deliver notes from the girls to their lovers, or run errands to the market or pharmacy. Often, thanks to his loose tongue and long-extinguished self-esteem, he’d worm his way into other people’s company and increase their expenses, and the money he borrowed he wouldn’t take elsewhere but would spend it right there on the women — perhaps only keeping some small change for cigarettes. And they tolerated him good-naturedly, out of habit.

“Here comes Vanka-Vstanka,” Nyurka announced when he, having already amicably shaken hands with Simeon the doorman, stopped in the doorway of the hall, long, in his uniform cap jauntily tilted. “Well, Vanka-Vstanka, let’s have it!”

“I have the honor to introduce myself,” Vanka-Vstanka immediately mimicked, saluting militarily, “secret honorary visitor of local pleasure establishments, Prince Butylkin, Count Nalivkin, Baron Tprutinkevich-Fyutinsky. To Mr. Beethoven! To Mr. Chopin!” he greeted the musicians. “Play me something from the opera ‘Brave and Glorious General Anisimov, or Mayhem in the Corridor.’ My respects to the political economist Zosya. Ah-ha! Only kiss on Easter? Noted. Ooh, my Tamalochka, my sweet little thing!”

Thus, with jokes and pinches, he went around to all the girls and finally sat down next to the plump Katya, who put her plump leg on his, rested her elbow on her knee, and her chin on her palm, and began to watch indifferently and intently as the surveyor rolled himself a cigarette.

“How do you not get tired of it, Vanka-Vstanka? You’re always rolling your ‘goat’s leg’ [a type of cigarette].”

Vanka-Vstanka immediately wiggled his eyebrows and scalp and began to speak in verse: