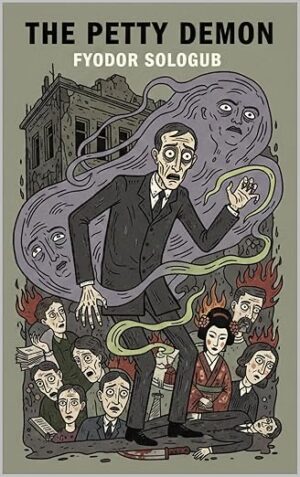

The Petty Demon by Fyodor Sologub: Read FREE Full Text Online (English Translation)

You can now read the full text for free of Fyodor Sologub’s notorious The Petty Demon. This essential Russian classic novel and masterpiece of Russian Symbolism is available for online reading here in a high-quality English translation.

Dive into this captivating exploration of moral decay and provincial life, and experience one of the most significant works by a major Russian author. Start reading instantly without any download required. This exclusive free access is your gateway to essential Russian literature.

You can also buy this book from us in the paperback edition via the link below.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

The Petty Demon by Fyodor Sologub

Page Count: 352Year: 1907READ FREEProducts search This unsettling masterpiece of Russian symbolism centers on Ardalion Peredonov, a paranoid and cruel provincial high school teacher whose descent into madness mirrors the moral decay of his entire community. Obsessed with securing a promotion and a comfortable marriage, Peredonov finds his trivial ambitions twisted by suspicion, filth, and escalating fear. He begins […]

€22.00 Login to Wishlist

First published in 1905, “Voprosy Zhizni”

Magazine, Russian Empire

This book is in the public domain

Reprint by Publishing House №10 2025

Publication date July 17, 2025

Translation from Russian

369 Pages, Font 12 pt, Bookman Old Style

Electronic edition, File size 663 KB

Cover design, Translate by Yulia Basharova

Copyright© Yulia Basharova

Table of Contents

I

After the festive liturgy, the parishioners dispersed to their homes. Some lingered in the churchyard, behind white stone walls, under old linden and maple trees, and chatted. Everyone was dressed up for the holiday, looked at each other amiably, and it seemed that in this town, people lived peacefully and amicably. And even cheerfully. But all this was only an illusion.

The gymnasium teacher Peredonov, standing in a circle of his friends, glumly looking at them with his small, swollen eyes from behind gold-rimmed glasses, told them:

“Princess Volchanskaya herself promised Varya, that’s for sure. As soon as, she says, she marries him, I’ll immediately get him the position of inspector.”

“But how can you marry Varvara Dmitrievna?” asked the red-faced Falastov, “She’s your sister! Has a new law come out that allows marrying sisters?”

Everyone burst out laughing. Peredonov’s usually rosy, indifferent-sleepy face turned ferocious.

“Third cousin…” he grumbled, looking angrily past his interlocutors.

“Did the princess promise you herself?” asked the dapper, pale, and tall Rutilov.

“Not me, but Varya,” Peredonov replied.

“Well, and you believe it,” Rutilov said animatedly. “Anyone can say anything. Why didn’t you go to the princess yourself?”

“Understand, Varya and I went, but we didn’t find the princess, we were only five minutes late,” Peredonov recounted, “She went to the village, will be back in three weeks, and I absolutely couldn’t wait, I had to come here for the exams.”

“Something’s doubtful,” Rutilov said and laughed, showing his decaying teeth.

Peredonov fell into thought. His companions dispersed. Only Rutilov remained with him.

“Of course,” Peredonov said, “I can marry anyone I want. Varvara isn’t the only one.”

“Naturally, any girl would go for you, Ardalyon Borysyich,” Rutilov confirmed.

They left the churchyard and walked slowly across the unpaved, dusty square. Peredonov said:

“But what about the princess? She’ll get angry if I ditch Varvara.”

“Well, what about the princess!” said Rutilov. “You’re not raising kittens with her. Let her give you the position first – you’ll have time to settle down. Otherwise, it’s just for nothing, seeing nothing!”

“That’s true…” Peredonov agreed thoughtfully.

“You tell Varvara that,” Rutilov persuaded. “First the position, otherwise, I don’t really believe it. Get the position, and then marry whoever you want. You’d better take one of my sisters – three of them, choose any. The young ladies are educated, smart, no flattery, not a match for Varvara. She’s not fit to tie their shoelaces.”

“Well-l…” Peredonov mumbled.

“True. What’s your Varvara? Here, smell this.”

Rutilov bent down, tore off a woolly stem of henbane, crumpled it with its leaves and dirty-white flowers, and, rubbing it all with his fingers, brought it to Peredonov’s nose. Peredonov winced at the unpleasant, heavy smell. Rutilov said:

“Rub it and throw it away – that’s your Varvara. She and my sisters – that, brother, is a big difference. Lively young ladies, energetic – take any, she won’t let you sleep. And young, too – the oldest is three times younger than your Varvara.”

Rutilov said all this, as was his custom, quickly and cheerfully, smiling, but he, tall and narrow-chested, seemed frail and fragile, and from under his new and fashionable hat, his sparse, short-cropped light hair stuck out rather sadly.

“Well, three times as young,” Peredonov weakly retorted, taking off and wiping his gold glasses.

“Yes, it’s true!” Rutilov exclaimed. “Look, don’t miss out while I’m alive, otherwise, they have their pride too – later you’ll want to, but it’ll be too late. But each of them would go for you with great pleasure.”

“Yes, everyone here falls in love with me,” Peredonov said with gloomy self-praise.

“Well, you see, so seize the moment,” Rutilov urged.

“The main thing for me would be that she’s not scrawny,” Peredonov said with longing in his voice. “I’d like a plump one.”

“Oh, don’t you worry about that,” Rutilov said ardently. “They are plump young ladies even now, and if they haven’t quite filled out, that’s only for a while. They’ll get married and they’ll get plump, like the eldest. Larisa, as you know, has become quite a pie.”

“I would marry,” Peredonov said, “but I’m afraid Varya will make a big scandal.”

“If you’re afraid of a scandal, then do this,” Rutilov said with a cunning smile: “Marry today, or tomorrow: you’ll come home with a young wife, and that’s that. Truly, if you want, I’ll arrange it, tomorrow evening? With whichever one you want?”

Peredonov suddenly burst out laughing, in short, loud bursts.

“Well, agreed? Is it a deal?” Rutilov asked.

Peredonov as suddenly stopped laughing and glumly said, softly, almost in a whisper:

“She’ll report me, the scoundrel.”

“She won’t report anything, there’s nothing to report,” Rutilov reassured him.

“Or she’ll poison me,” Peredonov whispered fearfully.

“Just rely on me for everything,” Rutilov ardently persuaded him, “I’ll arrange everything so subtly for you…”

“I won’t marry without a dowry,” Peredonov shouted angrily.

Rutilov was not at all surprised by this new jump in his gloomy interlocutor’s thoughts. He retorted with the same animation:

“Fool, are they dowerless? Well, is it a deal? Well, I’ll run, I’ll arrange everything. But mum’s the word, understand, not a peep to anyone!”

He shook Peredonov’s hand and ran off. Peredonov silently watched him. The Rutilov young ladies came to his mind, cheerful, mocking. An immodest thought forced a foul semblance of a smile onto his lips – it appeared for a moment and disappeared. A vague unease arose within him.

“What about the princess?” he thought. “Those girls have no money, and no patronage, but with Varvara, you’ll become an inspector, and then they’ll make you a director.”

He looked after the fussily scurrying Rutilov and thought maliciously: “Let him run around.”

And this thought gave him a sluggish and dull pleasure. But he grew bored because he was alone; he pulled his hat down over his forehead, furrowed his light eyebrows, and hastily set off home along the unpaved, empty streets, overgrown with creeping moss with white flowers, and watercress, a weed trampled in the mud.

Someone called him in a quiet and quick voice:

“Ardalyon Borysyich, come visit us.”

Peredonov raised his gloomy eyes and looked angrily over the fence. In the garden, behind the gate, stood Natalya Afanasyevna Vershina, a small, thin, dark-skinned woman, all in black, with black eyebrows and black eyes. She was smoking a cigarette in a dark cherry wood mouthpiece and smiling slightly, as if she knew something that isn’t spoken, but is smiled at. Not so much with words, but with light, quick movements, she invited Peredonov into her garden: she opened the gate, stepped aside, smiled entreatingly and at the same time confidently, and motioned with her hands – come in, why are you standing there.

And Peredonov entered, obeying her as if enchanting, silent movements. But he immediately stopped on the sandy path, where fragments of dry branches caught his eye, and looked at his watch.

“Time for breakfast,” he grumbled.

Although he had owned the watch for a long time, he still, as always when people were present, looked with pleasure at its large gold covers. It was twenty minutes to twelve. Peredonov decided he could stay a little while. He walked glumly behind Vershina along the paths, past the empty bushes of black and red currants, raspberries, and gooseberries.

The garden was yellow and mottled with fruits and late flowers. There were many fruit trees and ordinary trees and bushes: low spreading apple trees, round-leaved pears, linden trees, cherry trees with smooth shiny leaves, plum, honeysuckle. Red berries ripened on elderberry bushes. Siberian geranium bloomed thickly near the fence – small, pale pink flowers with purple veins.

Thistles poked their prickly purple heads from under the bushes. To one side stood a wooden house, small, greyish, with a single dwelling, and a wide porch leading to the garden. It seemed charming and cozy. And behind it, a part of the vegetable garden was visible. There, dry poppy pods swayed, and large, white-yellow daisy caps, yellow sunflower heads drooped before wilting, and among the useful herbs, umbrellas rose: white ones of wild parsnip and pale purple ones of spotted hemlock, light yellow buttercups and low spurges bloomed.

“Were you at the liturgy?” Vershina asked.

“I was,” Peredonov replied glumly.

“And Martha just came back,” Vershina recounted. “She often goes to our church. I even laugh: for whom, I say, Martha, do you go to our church? She blushes, stays silent. Let’s go, let’s sit in the arbor,” she said quickly and without any transition from what she had been saying before.

In the middle of the garden, in the shade of sprawling maples, stood an old, greyish arbor – three steps up, a moss-covered platform, low walls, six turned, bulging columns, and a six-slope roof.

Martha sat in the arbor, still dressed up from the liturgy. She wore a light dress with bows, but it didn’t suit her. The short sleeves exposed sharp, red elbows and strong, large hands. Martha, however, was not bad-looking. Her freckles didn’t spoil her. She was even considered pretty, especially among her own people, the Poles – there were quite a few of them living here.

Martha was rolling cigarettes for Vershina. She impatiently wanted Peredonov to look at her and be delighted. This desire revealed itself on her simple face with an expression of restless friendliness. However, it didn’t stem from Martha being in love with Peredonov: Vershina wanted to find her a match, the family was large – and Martha wanted to please Vershina, with whom she had been living for several months, since the funeral of Vershina’s old husband – to please her for herself and for her gymnasium student brother, who was also visiting here.

Vershina and Peredonov entered the arbor. Peredonov glumly greeted Martha and sat down – he chose a spot where a column would protect his back from the wind and where drafts wouldn’t blow into his ears. He looked at Martha’s yellow shoes with pink pom-poms and thought that they were trying to catch him as a groom. He always thought this when he saw young ladies who were amiable with him. He noticed only flaws in Martha – many freckles, large hands, and rough skin. He knew that her father, a nobleman, leased a small village about six versts from the town. The income was small, there were many children: Martha had finished pro-gymnasium, her son was studying in gymnasium, other children were even younger.

“May I pour you some beer?” Vershina asked quickly.

On the table were glasses, two bottles of beer, fine sugar in a tin box, a nickel silver spoon, soaked in beer.

“I’ll drink it,” Peredonov said curtly.

Vershina looked at Martha. Martha poured a glass, pushed it to Peredonov, and at the same time, a strange smile, half-frightened, half-joyful, played on her face. Vershina said quickly, as if spilling words:

“Put sugar in your beer.”

Martha pushed the tin with sugar to Peredonov. But Peredonov said irritably:

“No, that’s disgusting, with sugar.”

“What are you saying, it’s delicious,” Vershina dropped monotonously and quickly.

“Very delicious,” Martha said.

“Disgusting,” Peredonov repeated and looked angrily at the sugar.

“As you wish,” Vershina said and in the same voice, without stopping or transitioning, began to talk about something else: “Cherpnin is bothering me,” she said and laughed.

Martha also laughed. Peredonov looked on indifferently: he took no part in other people’s affairs – he didn’t like people, didn’t think about them except in connection with his own advantages and pleasures. Vershina smiled complacently and said:

“He thinks I’ll marry him.”

“Awfully cheeky,” Martha said, not because she thought so, but because she wanted to please and flatter Vershina.

“He was peeking through the window yesterday,” Vershina recounted. “He climbed into the garden when we were having supper. A tub stood under the window, we had put it out for the rain – it was full. It was covered with a board, the water wasn’t visible, he climbed onto the tub and looked into the window. And our lamp was on – he saw us, but we didn’t see him. Suddenly we heard a noise. We were scared at first, ran out. And it was him, he had fallen into the water. But he got out before us, ran away all wet – a wet trail on the path. And we recognized him by his back.”

Martha laughed with a thin, joyful laugh, like well-behaved children laugh. Vershina recounted everything quickly and monotonously, as if pouring it out – as she always said – and immediately fell silent, sitting and smiling with the corner of her mouth, and because of this, her whole dark and dry face wrinkled, and her teeth, blackened from smoking, slightly parted. Peredonov thought and suddenly burst out laughing. He always reacted slowly to what he found funny – his perceptions were slow and dull.

Vershina smoked cigarette after cigarette. She couldn’t live without tobacco smoke in front of her nose.

“We’ll be neighbors soon,” Peredonov announced.

Vershina cast a quick glance at Martha. She blushed slightly, looked at Peredonov with fearful anticipation, and then immediately looked away into the garden again.

“Are you moving?” Vershina asked. “Why?”

“Far from the gymnasium,” Peredonov explained. Vershina smiled distrustfully. More likely, she thought, he wants to be closer to Martha.

“But you’ve been living there for a long time, for several years,” she said.

“And the landlady’s a bitch,” Peredonov said angrily.

“Really?” Vershina asked distrustfully, and smiled crookedly.

Peredonov livened up a bit.

“She put up new wallpaper, but badly,” he recounted. “The pieces don’t match. Suddenly in the dining room, above the door, there’s a completely different pattern, the whole room has swirls and little flowers, but above the door it’s stripes and little nails. And the color is completely wrong. We almost didn’t notice, but Falastov came, he laughed. And everyone laughed.”

“Of course, such an outrage,” Vershina agreed.

“Only we’re not telling her that we’re moving out,” Peredonov said, lowering his voice. “We’ll find an apartment and leave, and we won’t tell her.”

“Naturally,” Vershina said.

“Otherwise, she’ll probably make a scandal,” Peredonov said, and fearful anxiety was reflected in his eyes. “And then I’ll have to pay her for a month, for such nastiness.”

Peredonov burst out laughing with joy that he would move out and not pay for the apartment.

“She’ll demand it,” Vershina remarked.

“Let her demand, I won’t give it,” Peredonov said angrily. “We went to Petersburg, so we didn’t use the apartment during that time.”

“But the apartment remained yours,” Vershina said.

“So what! She has to do repairs, so are we obliged to pay for the time we don’t live there? And most importantly – she’s awfully cheeky.”

“Well, the landlady is cheeky because your… sister is too fiery a person,” Vershina said with a slight hesitation on the word “sister.”

Peredonov frowned and stared ahead dully with half-sleepy eyes. Vershina started talking about something else. Peredonov pulled a caramel from his pocket, unwrapped it, and began to chew. He accidentally glanced at Martha and thought that she was envious and also wanted a caramel.

“Should I give her one or not?” Peredonov thought. “She’s not worth it. Or maybe I should give her one – so they don’t think I’m stingy. I have a lot, my pockets are full.”

And he pulled out a handful of caramels.

“Here,” he said and offered the candies first to Vershina, then to Martha, “good bonbons, expensive, thirty kopecks a pound.”

They each took one. He said:

“Take more. I have a lot, and good bonbons – I won’t eat bad ones.”

“Thank you, I don’t want any more,” Vershina said quickly and expressionlessly.

And Martha repeated the same words after her, but somewhat hesitantly. Peredonov looked at Martha distrustfully and said:

“Well, how can you not want any! Here.”

And he took one caramel for himself from the handful, and placed the rest in front of Martha. Martha smiled silently and bowed her head.

“Rude,” Peredonov thought, “doesn’t know how to thank properly.”

He didn’t know what to talk about with Martha. She wasn’t interesting to him, like all objects with which no pleasant or unpleasant relationships had been established for him by someone.

The rest of the beer was poured into Peredonov’s glass. Vershina looked at Martha.

“I’ll bring it,” Martha said. She always guessed without words what Vershina wanted.

“Send Vladya, he’s in the garden,” Vershina said.

“Vladislav!” Martha called out.

“Here,” the boy replied so close and so quickly, as if he had been eavesdropping.

“Bring two bottles of beer,” Martha said, “in the chest in the hallway.”

Soon Vladislav quietly ran up to the arbor, handed Martha the beer through the window, and bowed to Peredonov.

“Hello,” Peredonov said grimly, “how many bottles of beer have you guzzled today?”

Vladislav forced a smile and said:

“I don’t drink beer.”

He was a boy of about fourteen, with a freckled face like Martha’s, resembling his sister, awkward and sluggish in his movements. He was dressed in a coarse linen blouse.

Martha whispered to her brother. Both of them laughed. Peredonov looked at them suspiciously. When people laughed in his presence and he didn’t know why, he always assumed they were laughing at him. Vershina grew worried. She was about to call out to Martha. But Peredonov himself asked in an angry voice:

“What are you laughing at?”

Martha flinched, turned to him, and didn’t know what to say. Vladislav smiled, looking at Peredonov, and blushed slightly.

“That’s rude, in front of guests,” Peredonov reproached. “Are you laughing at me?” he asked.

Martha blushed, Vladislav was scared.

“Excuse me,” Martha said, “we weren’t laughing at you at all. We were talking about our own business.”

“A secret,” Peredonov said angrily. “It’s rude to talk about secrets in front of guests.”

“No, it’s not a secret,” Martha said, “but we were laughing because Vladya is barefoot and can’t come in here – he’s embarrassed.”

Peredonov calmed down, started inventing jokes about Vladya, then also treated him to a caramel.

“Martha, bring my black shawl,” Vershina said, “and while you’re at it, look in the kitchen, see how the pie is doing.”

Martha obediently left. She understood that Vershina wanted to talk to Peredonov, and she was glad, being lazy, that there was no hurry.

“And you go further away,” Vershina told Vladya, “there’s no need for you to hang around here.”

Vladya ran, and the sand could be heard rustling under his feet. Vershina cautiously and quickly looked sideways at Peredonov through the continuous smoke she exhaled. Peredonov sat silently, gazing straight ahead with a hazy look and chewing a caramel. He was pleased that they had left – otherwise, they might have laughed again. Although he now knew for sure that they weren’t laughing at him, a feeling of annoyance remained in him – just as after touching stinging nettle, the pain lingers and grows, even though the nettle is far away.

“Why aren’t you getting married?” Vershina suddenly spoke quickly and often. “What are you waiting for, Ardalyon Borysyich! Your Varvara is not a match for you, forgive me, I’ll say it directly.”

Peredonov ran his hand through his slightly dishevelled chestnut hair and said with gloomy solemnity:

“There’s no match for me here.”

“Don’t say that,” Vershina objected and smiled crookedly. “There’s much better here than her, and any girl would go for you.”

She flicked the ash from her cigarette with a decisive movement, as if putting an affirmative mark on something.

“I don’t need just any,” Peredonov replied.

“It’s not about just any,” Vershina said quickly. “And you don’t need to chase a dowry, as long as the girl is good. You yourself earn enough, thank God.”

“No,” Peredonov objected, “it’s more advantageous for me to marry Varvara. The princess promised her patronage. She’ll give me a good position,” Peredonov said with gloomy animation.

Vershina smiled slightly. Her whole wrinkled and dark face, as if smoke-stained, expressed condescending disbelief. She asked:

“Did she tell you that, the princess?” with emphasis on the word “you.”

“Not me, but Varvara,” Peredonov admitted, “but it’s all the same.”

“You rely too much on your sister’s words,” Vershina said maliciously. “Well, tell me, is she much older than you? By fifteen years? Or more? She’s almost fifty, isn’t she?”

“Oh, where on earth,” Peredonov said irritably, “she’s not even thirty yet.” Vershina laughed.

“Please tell me,” she said with unconcealed mockery in her voice, “but she looks much older than you. Of course, it’s none of my business, but from the outside, it’s a pity that such a good young man has to live not as he deserves according to his beauty and spiritual qualities.”

Peredonov self-satisfiedly surveyed himself. But there was no smile on his rosy face, and it seemed that he was offended that not everyone understood him as Vershina did. And Vershina continued:

“You’ll go far even without patronage. Surely the authorities will appreciate you! Why cling to Varvara! And you shouldn’t take a wife from the Rutilov girls either: they are frivolous, and you need a steady wife. Why don’t you take my Martha.”

Peredonov looked at his watch.

“Time to go home,” he said and began to say goodbye.

Vershina was sure that Peredonov was leaving because she had touched a raw nerve, and that he only didn’t want to talk about Martha now out of indecision.

II

Varvara Dmitrievna Maloshina, Peredonov’s cohabitant, awaited him, sloppily dressed but carefully powdered and rouged.

Pies with jam were baking for breakfast; Peredonov loved them. Varvara waddled around the kitchen on high heels, hurrying to prepare everything for his arrival. Varvara feared that the maid, Natalya, a pockmarked, stout girl, would steal a pie, or even more. Therefore, Varvara stayed in the kitchen and, as usual, scolded the maid. A grumbling, greedy expression perpetually lay on her wrinkled face, which still bore traces of her former beauty.

As always upon returning home, Peredonov was seized by discontent and melancholy. He entered the dining room noisily, tossed his hat onto the windowsill, sat down at the table, and shouted:

“Varya, serve!”

Varvara carried dishes from the kitchen, quickly shuffling on her high heels, worn for show, and waited on Peredonov herself. When she brought the coffee, Peredonov leaned towards the steaming glass and sniffed. Varvara became anxious and timidly asked him:

“What is it, Ardalyon Borysyich? Does the coffee smell of anything?”

Peredonov glanced at her glumly and said angrily:

“I’m sniffing to see if there’s poison in it.”

“Oh, Ardalyon Borysyich!” Varvara exclaimed, startled. “God be with you, why would you think that?”

“You’ve stirred up a storm!” he grumbled.

“What profit is it to me to poison you?” Varvara argued, “Stop playing the fool!”

Peredonov continued sniffing for a long time, finally calmed down and said:

“If there’s poison, you’ll definitely smell a heavy odor, you just have to sniff closer, into the very steam.”

He was silent for a moment and then suddenly said with malice and mockery:

“The princess!”

Varvara became agitated.

“What princess? What about the princess?”

“The princess is this,” Peredonov said, “no, let her first give me the position, and only then will I marry. You write her that.”

“But you know, Ardalyon Borysyich,” Varvara began in a persuasive voice, “that the princess only promises when I get married. Otherwise, it’s awkward for her to ask for you.”

“Write that we’re already married,” Peredonov said quickly, pleased with his invention. Varvara was taken aback at first, but quickly recovered and said:

“Why lie — the princess can check. No, you’re better off setting a wedding date. And it’s time to sew the dress.”

“What dress?” Peredonov asked glumly.

“Are we going to get married in this drab outfit?” Varvara cried. “Give me money, Ardalyon Borysyich, for the dress.”

“Are you preparing for your grave?” Peredonov asked maliciously.

“You brute, Ardalyon Borysyich!” Varvara exclaimed reproachfully.

Suddenly, Peredonov wanted to tease Varvara. He asked:

“Varvara, do you know where I was?”

“Well, where?” Varvara asked anxiously.

“At Vershina’s,” he said and burst out laughing.

“Found yourself some company,” Varvara cried maliciously, “nothing to say!”

“I saw Martha,” Peredonov continued.

“All freckled,” Varvara said with growing malice, “and a mouth from ear to ear, you could sew it onto a frog.”

“But she’s prettier than you,” Peredonov said. “I’ll just go and marry her.”

“Just you marry her,” Varvara shouted, red and trembling with anger, “I’ll burn her eyes out with acid!”

“I want to spit on you,” Peredonov said calmly.

“You won’t spit!” Varvara cried.

“Oh yes, I will,” Peredonov said.

He stood up and, with a dull and indifferent expression, spat in her face.

“Pig!” Varvara said rather calmly, as if the spit had refreshed her.

And she began to wipe herself with a napkin. Peredonov was silent. Lately, he had become ruder than usual with Varvara. And even before, he had treated her badly. Encouraged by his silence, she spoke louder:

“Truly, a pig. Hit me right in the face.”

A bleating, almost sheep-like voice was heard from the hallway.

“Don’t shout,” Peredonov said, “guests.”

“Oh, that’s Pavlushka,” Varvara replied with a smirk.

Pavel Vasilyevich Volodin, a young man who, both in face and mannerisms, remarkably resembled a lamb, entered with a joyful, loud laugh: his hair was curly like a lamb’s, his eyes bulging and dull—everything about him was like a cheerful lamb—a foolish young man. He was a carpenter, had previously studied at a trade school, and now served as a craft teacher at the city school.

“Ardalyon Borysyich, old friend!” he cried joyfully. “You’re home, drinking coffee, and here I am, right here.”

“Natashka, bring the third spoon!” Varvara shouted.

From the kitchen, the clinking of Natalya’s single remaining teaspoon could be heard; the others were hidden.

“Eat, Pavlushka,” Peredonov said, and it was clear he wanted to feed Volodin. “And I, brother, will soon be an inspector – the princess promised Varya.”

Volodin cheered and laughed.

“Ah, the future inspector drinking coffee!” he shouted, slapping Peredonov on the shoulder.

“And you think it’s easy to become an inspector? They’ll report you – and that’s the end of it.”

“What is there to report?” Varvara asked with a smirk.

“Plenty. They’ll say I read Pisarev – and that’s it!”

“And you, Ardalyon Borysyich, put that Pisarev on the back shelf,” Volodin advised, giggling.

Peredonov looked at Volodin warily and said:

“Maybe I never even had Pisarev. Want a drink, Pavlushka?”

Volodin protruded his lower lip, made a significant face of a man who knew his worth, and, inclining his head like a sheep, said:

“If it’s for company, I’m always ready to drink, but otherwise – not at all.”

And Peredonov was always ready to drink too. They drank vodka and had sweet pies for a snack.

Suddenly, Peredonov splashed the remaining coffee from his glass onto the wallpaper. Volodin’s sheep-like eyes widened, and he looked around in surprise. The wallpaper was stained and torn. Volodin asked:

“What’s wrong with your wallpaper?”

Peredonov and Varvara burst out laughing.

“To spite the landlady,” Varvara said. “We’re moving out soon. Just don’t you chatter.”

“Excellent!” Volodin cried and laughed joyfully.

Peredonov walked to the wall and began to beat it with his soles. Volodin, following his example, also kicked the wall. Peredonov said:

“We always mess up the walls when we eat – let her remember.”

“What messes he’s made!” Volodin exclaimed with delight.

“Irishka will be dumbfounded,” Varvara said with a dry and wicked laugh.

And all three, standing before the wall, spat on it, tore the wallpaper, and beat it with their boots. Then, tired and satisfied, they stepped away.

Peredonov bent down and picked up the cat. The cat was fat, white, and ugly. Peredonov tormented it — pulling its ears, its tail, shaking it by the neck. Volodin laughed joyfully and suggested to Peredonov what else could be done.

“Ardalyon Borysyich, blow in its eyes! Stroke it against the fur!”

The cat hissed and tried to break free but dared not show its claws — for that, it was severely beaten. Finally, Peredonov grew bored with the game, and he threw the cat.

“Listen, Ardalyon Borysyich, what I wanted to tell you,” Volodin began. “I kept thinking the whole way not to forget, and I almost did.”

“Well?” Peredonov asked glumly.

“You love sweets,” Volodin said joyfully, “and I know a dish that will make you lick your fingers.”

“I know all the tasty dishes myself,” Peredonov said.

Volodin made an offended face.

“Perhaps,” he said, “you, Ardalyon Borysyich, know all the tasty dishes made in your homeland, but how can you know all the tasty dishes made in my homeland if you’ve never been to my homeland?”

And, pleased with the convincingness of his retort, Volodin laughed, bleating.

“In your homeland, they eat dead cats,” Peredonov said angrily.

“Excuse me, Ardalyon Borysyich,” Volodin said in a squeaky, laughing voice, “perhaps it’s in your homeland that they choose to eat dead cats, we won’t touch upon that, but you’ve never eaten yearly.”

“No, I haven’t,” Peredonov admitted.

“What kind of dish is that?” Varvara asked.

“Well, it’s this,” Volodin began to explain, “do you know kutya?”

“Well, who doesn’t know kutya?” Varvara replied with a smirk.

“So, millet kutya, with raisins, with sugar, with almonds — that’s yearly.”

And Volodin recounted in detail how “yearly” was cooked in his homeland. Peredonov listened with melancholy. Kutya – was Pavlushka trying to mark him for the deceased or something?

Volodin suggested:

“If you want everything to be just right, you give me the ingredients, and I’ll cook it for you.”

“Let the goat into the garden,” Peredonov said glumly.

“He’ll probably sprinkle something else in,” he thought. Volodin was offended again.

“If you think, Ardalyon Borysyich, that I’ll steal your sugar, then you’re mistaken,” he said, “I don’t need your sugar.”

“Oh, stop playing the fool,” Varvara interrupted. “You know he’s picky about everything. Just come and cook it.”

“You’ll be the one eating it yourself,” Peredonov said.

“Why’s that?” Volodin asked, his voice trembling with offense.

“Because it’s disgusting.”

“As you wish, Ardalyon Borysyich,” Volodin said, shrugging, “but I only wanted to please you, and if you don’t want it, then as you wish.”

“And how did the general brush you off?” Peredonov asked.

“Which general?” Volodin replied with a question, blushing and pouting his lower lip in offense.

“Oh, we heard, we heard,” Peredonov said.

Varvara smirked.

“Excuse me, Ardalyon Borysyich,” Volodin began hotly, “you heard, but perhaps you didn’t hear everything. I’ll tell you how it all happened.”

“Well, tell me,” Peredonov said.

“It was the day before yesterday,” Volodin recounted, “around this very time. In our school, as you know, repairs are being done in the workshop. And so, if you please, Veriga comes with our inspector to inspect, and we are working in the back room. Good. I won’t touch on why Veriga came, what he needed – that’s not my business. Let’s say I know he’s the marshal of the nobility and has no connection to our school – but I won’t touch on that. He comes – and let him, we don’t bother them, we work little by little – suddenly they enter our room, and Veriga, if you please, is wearing a hat.”

“He showed you disrespect,” Peredonov said glumly.

“If you please,” Volodin eagerly picked up, “we have an icon hanging, and we ourselves are hatless, but he suddenly appears like a Mameluke. And I took the liberty of telling him, quietly, nobly: your Excellency, I said, please take off your hat, because, I said, there is an icon here. Did I say it correctly?” Volodin asked and widened his eyes inquiringly.

“Clever, Pavlushka,” Peredonov shouted, “he deserved it.”

“Of course, why let them get away with it,” Varvara supported him. “Well done, Pavel Vasilyevich.”

Volodin, with the air of a wrongly offended man, continued:

“And he suddenly took it upon himself to say to me: every cricket knows its hearth. He turned and left. That’s how it all happened, and nothing more.”

Volodin still felt like a hero. Peredonov, as a consolation, gave him a caramel.

Another guest arrived, Sofya Efimovna Prepolovenskaya, the forester’s wife, a plump woman with a good-naturedly cunning face and graceful movements. She was seated for breakfast. She slyly asked Volodin:

“Why are you, Pavel Vasilyevich, visiting Varvara Dmitrievna so often?”

“I did not come to Varvara Dmitrievna,” Volodin replied modestly, “but to Ardalyon Borysyich.”

“Haven’t you fallen in love with someone?” Prepolovenskaya asked, chuckling.

Everyone knew that Volodin was looking for a bride with a dowry, had proposed to many, and had been rejected. Prepolovenskaya’s joke seemed inappropriate to him. In a trembling voice, reminding everyone by his whole demeanor of an offended lamb, he said:

“If I have fallen in love, Sofya Efimovna, it concerns no one but myself and that person, and you should step aside in such a manner.”

But Prepolovenskaya wouldn’t stop.

“Look,” she said, “if you make Varvara Dmitrievna fall in love with you, who will bake sweet pies for Ardalyon Borysyich then?”

Volodin pouted his lips, raised his eyebrows, and no longer knew what to say.

“Well, why wouldn’t she want to,” Prepolovenskaya replied, “you’re too modest at the wrong time.”

“And maybe I won’t want to either,” Volodin said coyly. “Maybe I don’t want to marry other people’s sisters. Maybe I have a cousin growing up in my homeland.”

He had already started to believe that Varvara wouldn’t mind marrying him. Varvara was angry. She considered Volodin a fool; besides, he earned four times less than Peredonov. Prepolovenskaya, however, wanted to marry Peredonov to her sister, a plump priest’s daughter. Therefore, she tried to cause a quarrel between Peredonov and Varvara.

“Why are you matchmaking for me?” Varvara said irritably, “You’d better matchmake your youngest for Pavel Vasilyevich.”

“Why would I try to win him away from you!” Prepolovenskaya playfully objected.

Prepolovenskaya’s jokes gave a new turn to Peredonov’s slow thoughts; and the “yearly” had firmly settled in his head. Why did Volodin invent such a dish? Peredonov didn’t like to reflect. In the first moment, he always believed whatever he was told. So he also believed in Volodin’s infatuation with Varvara. He thought: they’ll get him tangled up with Varvara, and then, when they go to the inspector’s position, they’ll poison him on the road with yearly and replace him with Volodin: he’ll be buried as Volodin, and Volodin will be the inspector. What a clever plan!

Suddenly, a noise was heard in the hallway. Peredonov and Varvara were frightened: Peredonov fixed his narrowed eyes motionlessly on the door. Varvara crept to the living room door, barely opened it, peered in, then just as quietly, on tiptoes, balancing with her hands and smiling confusedly, returned to the table. Squealing shouts and noise came from the hallway, as if someone was fighting there. Varvara whispered:

“Yershikha is completely drunk, Natashka isn’t letting her in, but she’s pushing into the living room.”

“What should we do?” Peredonov asked, frightened.

“We need to move to the living room,” Varvara decided, “so she doesn’t get in here.”

They went into the living room, closing the doors tightly behind them. Varvara went into the hallway with a faint hope of detaining the landlady or seating her in the kitchen. But the brazen woman burst into the living room anyway. With hands on hips, she stopped at the threshold and spewed abusive words as a general greeting. Peredonov and Varvara bustled around her, trying to seat her on a chair closer to the hallway and further from the dining room. Varvara brought her vodka, beer, and pies from the kitchen on a tray. But the landlady wouldn’t sit down, wouldn’t take anything, and kept trying to get into the dining room, but she couldn’t find the door. She was red, disheveled, dirty, and reeked of vodka from afar. She shouted:

“No, you seat me at your table. Why are you bringing me things on a tray! I want to eat on the tablecloth. I’m the landlady, so you respect me. Don’t look at me just because I’m drunk. But I’m honest, I’m my husband’s wife.”

Varvara, smirking timidly and insolently, said:

“Oh, we know.”

Yershova winked at Varvara, chuckled hoarsely, and defiantly snapped her fingers. She became increasingly brazen.

“Sister!” she cried, “we know what kind of sister you are. And why doesn’t the directress visit you, huh? What?”

“Don’t shout,” Varvara said. But Yershova shouted even louder:

“How can you tell me what to do! I’m in my own house, I do what I want. If I want to, I’ll kick you out right now, and not a trace of your spirit will remain. But I am merciful to you. Live, it’s fine, just don’t be impudent.”

Meanwhile, Volodin and Prepolovenskaya sat modestly by the window and remained silent. Prepolovenskaya smiled slightly, glancing askance at the brawler, while pretending to look out at the street. Volodin sat with an offended, significant expression on his face.

Yershova momentarily became good-natured and said to Varvara in a friendly manner, smiling at her drunkenly and cheerfully, and patting her on the shoulder:

“No, you listen to me, I’ll tell you something – you seat me at your table, and give me some noble conversation. And give me some sweet jams, respect the mistress of the house, that’s it, my dear girl.”

“Here are your pies,” Varvara said.

“I don’t want pies, I want noble jams,” Yershova shouted, waving her arms and smiling blissfully, “the gentry eat tasty jams, oh, they’re tasty!”

“I don’t have any jams for you,” Varvara replied, growing bolder as the landlady became more cheerful, “here, they’re giving you pies, so eat them.”

Suddenly, Yershova found the door to the dining room. She roared furiously:

“Get out of the way, you viper!”

She pushed Varvara away and lunged for the door. They didn’t manage to stop her. Head bowed, fists clenched, she burst into the dining room, flinging the door open with a crash. There, she stopped near the threshold, saw the stained wallpaper, and whistled piercingly. She put her hands on her hips, boldly stuck out her leg, and shouted furiously:

“Ah, so you really want to move out!”

“What are you doing, Irinya Stepanovna,” Varvara said with a trembling voice, “we’re not even thinking of it, stop fooling around.”

“We’re not going anywhere,” Peredonov confirmed, “we’re fine here.”

The landlady didn’t listen, approached the bewildered Varvara, and waved her fists in her face. Peredonov stood behind Varvara. He would have run away, but he was curious to see the landlady and Varvara fight.

“I’ll stand on one leg, pull the other, tear you in half!” Yershova screamed fiercely.

“What are you doing, Irinya Stepanovna,” Varvara pleaded, “stop it, we have guests.”

“Bring the guests here!” Yershova shouted, “It’s your guests I want!”

Yershova, staggering, rushed into the living room and, suddenly changing her speech and her whole demeanor completely, humbly said to Prepolovenskaya, bowing low to her, almost falling to the floor:

“My dear lady, Sofya Efimovna, forgive me, a drunken woman. But listen to what I’ll tell you. You visit them, but do you know what she says about your sister? And to whom? To me, a drunken shoemaker! Why? So I would tell everyone, that’s why!”

Varvara turned crimson and said:

“I didn’t tell you anything.”

“You didn’t tell me? You foul filth?” Yershova shouted, approaching Varvara with clenched fists.

“Well, shut up,” Varvara mumbled, embarrassed.

“No, I won’t shut up,” Yershova cried maliciously and turned to Prepolovenskaya again. “That she supposedly lives with your husband, your sister, that’s what she told me, the vile creature.”

Sofya flashed angry and cunning eyes at Varvara, stood up, and said with a feigned laugh:

“Thank you very much, I didn’t expect that.”

“You’re lying!” Varvara shrieked at Yershova.

Yershova angrily grunted, stamped her foot, waved her hand at Varvara, and immediately turned to Prepolovenskaya again:

“And what about you, dear lady, what does the master say about you! That you supposedly used to run around, and then got married! These are the kind of people they are, the vilest people! Spit in their faces, good lady, don’t get involved with such vile people.”

Prepolovenskaya blushed and silently went to the hallway. Peredonov ran after her, making excuses.

“She’s lying, don’t believe her. I only once said in front of her that you’re a fool, and that was out of spite, but honestly, I said nothing else – she made it all up herself.”

Prepolovenskaya calmly replied:

“Oh, Ardalyon Borysyich! I see she’s drunk, she doesn’t even remember what she’s blabbering about. But why do you allow all this in your house?”

“Go figure,” Peredonov replied, “what can you do with her!”

Prepolovenskaya, embarrassed and angry, was putting on her jacket. Peredonov didn’t think to help her. He was still muttering something, but she was no longer listening to him. Then Peredonov returned to the living room. Yershova began to noisily reproach him. Varvara ran out onto the porch and comforted Prepolovenskaya:

“You know what a fool he is – he doesn’t know what he’s saying himself.”

“Oh, come now, why are you worrying,” Prepolovenskaya replied. “A drunken woman can blurt out anything.”

Near the house, in the yard, where the porch led out, there was dense, tall nettle growing. Prepolovenskaya smiled slightly, and the last shadow of dissatisfaction left her white and full face. She became as amiable and kind to Varvara as before. The offense would be avenged without a quarrel. Together, they went into the garden to wait out the landlady’s invasion.

Prepolovenskaya kept looking at the nettle, which grew abundantly along the fences in the garden as well. She finally said:

“You have so much nettle. Don’t you need it?”

Varvara laughed and replied:

“Well, what do I need it for!”

“If you don’t mind, I should gather some from you, because we don’t have any,” Prepolovenskaya said.

“But what do you need it for?” Varvara asked with surprise.

“Oh, I need it,” Prepolovenskaya said, chuckling.

“Sweetheart, tell me, what for?” begged the curious Varvara.

Prepolovenskaya, leaning towards Varvara’s ear, whispered:

“Rubbing yourself with nettle – you won’t lose weight. That’s why my Genichka is so plump from nettle.”

It was known that Peredonov preferred plump women and criticized thin ones. Varvara was distressed that she was thin and kept losing weight. How to gain more fat? – this was one of her main concerns. She asked everyone: do you know any remedies? Now Prepolovenskaya was sure that Varvara, following her instructions, would diligently rub herself with nettle, and thus punish herself.

III

Peredonov and Yershova went out into the yard. He mumbled:

“Well, I’ll be.”

She was screaming at the top of her lungs and was cheerful. They were about to dance. Prepolovenskaya and Varvara slipped through the kitchen into the drawing-rooms and sat by the window to see what would happen in the yard.

Peredonov and Yershova embraced and started dancing on the grass around the pear tree. Peredonov’s face remained as dull as before and expressed nothing. Mechanically, as if on an inanimate object, his gold spectacles bounced on his nose and his short hair on his head. Yershova squealed, shrieked, waved her arms, and swayed all over.

She called out to Varvara through the window:

“Hey, you, haughty one, come out and dance! Are you too good for our company?”

Varvara turned away.

“To hell with you! I’m tired!” Yershova cried, then flopped onto the grass and dragged Peredonov down with her.

They sat embraced, then danced again. And so it repeated several times: they would dance, then rest under the pear tree, on a bench, or directly on the grass.

Volodin was genuinely amused, watching the dancers from the window. He laughed, made hilarious faces, writhed, bent his knees upwards, and exclaimed:

“Look at them go! What fun!”

“That cursed bitch!” Varvara said angrily.

“Bitch,” Volodin agreed, laughing, “just you wait, dear landlady, I’ll fix you. Let’s mess up the living room too. It doesn’t matter now, she won’t be back today, she’ll get tired out there on the grass, go to sleep.”

He burst into bleating laughter and bounced around like a ram. Prepolovenskaya egged him on:

“Of course, mess it up, Pavel Vasilyevich, why bother looking out for her. If she does come, you can tell her she did it herself with drunken eyes.”

Volodin, jumping and laughing, ran into the living room and began to scuff his soles on the wallpaper.

“Varvara Dmitrievna, give me a rope!” he cried.

Varvara, waddling like a duck, went through the living room into the bedroom and brought back a frayed and knotted end of a rope. Volodin made a loop, placed a chair in the middle of the room, and hung the loop on the lamp hook.

“This is for the landlady!” he cried. “So she has something to hang herself on out of spite when you leave!”

Both ladies shrieked with laughter.

“Give me a scrap of paper!” Volodin cried, “And a pencil.”

Varvara rummaged further in the bedroom and brought out a torn piece of paper and a pencil. Volodin wrote: “for the landlady” and attached the paper to the loop. He did all this with comical grimaces. Then he again began to jump furiously along the walls, kicking them with his soles and shaking all over. The whole house was filled with his squeals and bleating laughter. The white cat, ears pressed back in fear, peered out from the bedroom and, apparently, didn’t know where to run.

Peredonov finally broke free from Yershova and returned home alone – Yershova was indeed tired and had gone home to sleep. Volodin met Peredonov with joyful laughter and a shout:

“We messed up the living room too! Hooray!”

“Hooray!” Peredonov shouted and laughed loudly and in short bursts, as if firing off his laughter.

The ladies also shouted “hooray.” General merriment began. Peredonov shouted:

“Pavlushka, let’s dance!”

“Let’s go, Ardalyosha,” Volodin replied, giggling foolishly.

They danced under the loop, both clumsily kicking their legs high. The floor trembled under Peredonov’s heavy feet.

“Ardalyon Borysyich has really danced up a storm,” Prepolovenskaya remarked, smiling slightly.

“Don’t even mention it, he has all sorts of whims,” Varvara replied grumblingly, yet admiring Peredonov.

She genuinely thought he was handsome and a fine fellow. His most foolish actions seemed appropriate to her. He was neither funny nor repulsive to her.

“Chant the funeral service for the landlady!” Volodin cried. “Bring a pillow!”

“What won’t they think of!” Varvara said, laughing.

She threw a pillow in a dirty chintz pillowcase from the bedroom. The pillow was placed on the floor for the landlady, and they began to chant her funeral service with wild, squealing voices. Then they called Natalya, made her crank the orchestrion, and all four of them danced a quadrille, making absurd contortions and kicking their legs high.

After the dance, Peredonov became generous. A dull and gloomy animation shone on his swollen face. A resolution, almost mechanical, seized him – perhaps a result of intense physical activity. He pulled out his wallet, counted out several banknotes, and, with a proud and boastful face, threw them in Varvara’s direction.

“Take it, Varvara!” he cried. “Sew yourself a wedding dress.”

The banknotes scattered across the floor. Varvara quickly picked them up. She was not at all offended by such a method of giving. Prepolovenskaya thought maliciously: “Well, we’ll see who wins,” and smiled cunningly. Volodin, of course, didn’t think to help Varvara pick up the money.

Soon Prepolovenskaya left. In the hallway, she met a new guest, Grushina.

Maria Osipovna Grushina, a young widow, had a somewhat prematurely worn appearance. She was thin, and her dry skin was covered in small, as if dusty, wrinkles. Her face was not devoid of pleasantness, but her teeth were dirty and black. Her hands were thin, her fingers long and tenacious, with dirt under her nails. At a glance, she didn’t seem particularly dirty, but she gave the impression that she never washed, only shook herself out along with her clothes. One might think that if you hit her several times with a cane, a column of dust would rise to the sky.

Her clothes hung in crumpled folds, as if just taken out of a tightly tied knot where they had long lain crumpled. Grushina lived on a pension, small commissions, and lending money against the security of real estate. She mostly engaged in immodest conversations and attached herself to men, hoping to find a groom. Someone from the single civil servants always rented a room in her house.

Varvara greeted Grushina joyfully: she had business with her. Grushina and Varvara immediately began to talk about servants and whispered. The curious Volodin sat next to them and listened. Peredonov sat glumly and alone at the table, kneading the end of the tablecloth with his hands.

Varvara complained to Grushina about her Natalya. Grushina pointed out a new servant to her, Klavdia, and praised her. They decided to go for her right away, to Samorodina River, where she was currently living with an excise officer who had recently been transferred to another city. Varvara was only stopped by the name. She asked in bewilderment:

“Klavdia? But what am I to call her? Klashka, perhaps?”

Grushina advised:

“You call her Klavdyushka.”

Varvara liked this. She repeated:

“Klavdyushka, dyushka.”

And she laughed with a creaky laugh. It should be noted that “dyushka” in our town is what pigs are called. Volodin grunted. Everyone burst out laughing.

“Dyushka, dyushenka,” Volodin babbled between fits of laughter, contorting his foolish face and pouting his lips.

And he grunted and played the fool until he was told he was annoying. Then he walked away with an offended face, sat next to Peredonov, and, bowing his steep forehead like a sheep, stared at the stain-covered tablecloth.

At the same time, on the way to Samorodina River, Varvara decided to buy fabric for the wedding dress. She always went shopping with Grushina: she helped her make a choice and haggle.

Stealthily from Peredonov, Varvara stuffed various dishes, sweet pies, and treats into Grushina’s deep pockets for her children. Grushina guessed that her services would be much needed by Varvara today for something.

Varvara’s narrow shoes and high heels didn’t allow her to walk much. She quickly got tired. Therefore, she more often rode in cabs, although there were no great distances in our town. Recently, she had been frequenting Grushina’s. The cab drivers had already noticed this; there were only about twenty of them in total. When Varvara got in, they no longer even asked where to take her.

They settled into the gig and rode to the home of the gentlemen with whom Klavdia was living, to inquire about her. The streets were almost everywhere dirty, although it had rained only yesterday evening. The gig only occasionally rattled over the stone paving and then again got stuck in the sticky mud of the unpaved streets.

But Varvara’s voice rattled continuously, often accompanied by Grushina’s sympathetic chatter.

“My goose was at Marfushka’s again,” Varvara said.

Grushina replied with sympathetic malice:

“They’re trying to catch him. Of course, he’s quite a catch, especially for her, Marfushka. She wouldn’t even dream of such a thing.”

“I really don’t know what to do,” Varvara complained, “he’s become so prickly, it’s just dreadful. Believe me, my head is spinning. If he gets married, I’ll be out on the street.”

“Oh, darling, Varvara Dmitrievna,” Grushina comforted, “don’t think that. He’ll never marry anyone but you. He’s used to you.”

“Sometimes he leaves at night, and I can’t fall asleep,” Varvara said. “Who knows, maybe he’s getting married somewhere. Sometimes I suffer all night. Everyone is after him: and the three Rutilov mares – they cling to everyone – and Zhenka, the fat-faced one.”

And Varvara complained for a long time, and from all her conversation, Grushina saw that she had something else, some request, and rejoiced in advance at the prospect of earning.

Klavdia was liked. The excise officer’s wife praised her. She was hired and told to come this evening, as the excise officer was leaving today.

Finally, they arrived at Grushina’s house. Grushina lived in her own small, rather untidy house, with her three small children, ragged, dirty, stupid, and mean, like scalded puppies. The frank conversation only now began.

“My fool Ardalyoshka,” Varvara began, “demands that I write to the princess again. But why should I write to her for nothing! She won’t answer, or she’ll answer something unpleasant. Our acquaintance isn’t that great.”

Princess Volchanskaya, with whom Varvara had once lived as a household seamstress for simple tasks, could have patronized Peredonov: her daughter was married to Privy Councilor Shchepkin, an important person in the educational department. She had already written to Varvara in response to her requests last year that she would not ask for Varvara’s fiancé, but for a husband – that was a different matter, on occasion it might be possible to ask. That letter did not satisfy Peredonov: it only gave vague hope, and did not state directly that the princess would definitely get Varvara’s husband an inspector’s position. To clarify this misunderstanding, they had gone to Petersburg today; Varvara had visited the princess, then brought Peredonov to her, but deliberately delayed this visit so that they did not find the princess: Varvara understood that the princess would at best limit herself to advice to marry sooner and a few vague promises to ask on occasion – promises that would be completely insufficient for Peredonov. And Varvara decided not to show the princess to Peredonov.

“I rely on you as on a rock,” Varvara said, “help me, my dear Maria Osipovna.”

“How can I help, darling Varvara Dmitrievna?” Grushina asked. “You know, I’m ready to do anything for you that’s possible. Don’t you want me to tell your fortune?”

“Oh, I know your fortune-telling,” Varvara said with a laugh, “no, you must help me differently.”

“How?” Grushina asked with anxious and joyful anticipation.

“Very simply,” Varvara said, smirking, “you write a letter, as if from the princess, in her hand, and I’ll show it to Ardalyon Borysyich.”

“Oh, darling, what are you saying, how can that be!” Grushina began, pretending to be frightened, “If they find out about this, what will happen to me?”

Varvara was not at all embarrassed by her answer, pulled a crumpled letter from her pocket and said:

“Here, I even took the princess’s letter for you as a sample.”

Grushina refused for a long time. Varvara clearly saw that Grushina would agree, but that she wanted to get more for it. And Varvara wanted to give less. And she carefully increased her promises, promised various small gifts, an old silk dress, and finally Grushina saw that Varvara would not give anything more. Pitiful words simply poured from Varvara’s tongue. Grushina pretended that she was agreeing only out of pity, and took the letter.

IV

The billiard room was smoky and filled with cigarette fumes. Peredonov, Rutilov, Falastov, Volodin, and Murin—a landowner of enormous stature, with a foolish appearance, owner of a small estate, a shrewd and wealthy man—all five of them, having finished their game, were preparing to leave.

It was evening. On the dirty plank table stood many empty beer bottles. The players, who had drunk a lot during the game, were flushed and boisterously drunk. Rutilov alone maintained his usual sickly pallor. He also drank less than the others, and even after heavy drinking, he would only become paler.

Crude words hung in the air. No one was offended by this: it was friendly banter.

Peredonov had lost, as almost always. He played billiards poorly. But he maintained an unperturbed gloom on his face and paid reluctantly. Murin shouted loudly:

“Fire!”

And aimed a cue at Peredonov. Peredonov cried out in fear and ducked. A foolish thought flashed through his mind that Murin wanted to shoot him. Everyone burst out laughing. Peredonov muttered irritably:

“I can’t stand such jokes.”

Murin already regretted scaring Peredonov: his son studied at the gymnasium, and therefore he considered it his duty to please the gymnasium teachers in every way possible. Now he began to apologize to Peredonov and treated him to wine and seltzer.

Peredonov said glumly:

“My nerves are a bit frayed. I’m unhappy with our director.”

“The future inspector lost,” Volodin shouted in a bleating voice, “pity about the money!”

“Unlucky in cards, lucky in love,” Rutilov said, chuckling and showing his decaying teeth.

Peredonov was already in a bad mood from losing and from fright, and now they started teasing him about Varvara.

He shouted:

“I’ll get married, and Varvara out!”

His friends laughed and taunted him:

“Oh no, you wouldn’t dare.”

“Oh yes, I would. I’ll go propose tomorrow.”

“A bet! Is it on?” Falastov suggested, “Ten rubles.”

But Peredonov felt bad about the money – if he lost, he’d have to pay. He turned away and remained glumly silent.

At the garden gate, they parted ways and went in different directions. Peredonov and Rutilov walked together. Rutilov began to persuade Peredonov to marry one of his sisters immediately.

“I’ve arranged everything, don’t worry,” he insisted.

“There was no announcement,” Peredonov countered.

“I’ve arranged everything, I tell you,” Rutilov insisted. “I found a priest who knows you’re not related.”

“There are no groomsmen,” Peredonov said.

“Well, there aren’t any. We’ll get groomsmen right away, I’ll send for them, and they’ll come straight to the church. Or I’ll go pick them up myself. We couldn’t do it earlier, your sister would have found out and interfered.”

Peredonov fell silent and looked around wistfully at the dark, silent houses beyond sleepy little gardens and rickety fences.

“Just wait at the gate,” Rutilov said persuasively, “I’ll bring out any one you want. Well, listen, I’ll prove it to you right now. Two times two is four, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” Peredonov replied.

“Well, there you go, two times two is four, so you should marry my sister.”

Peredonov was astonished.

“That’s true,” he thought, “of course, two times two is four.” And he looked with respect at the reasonable Rutilov. “I’ll have to get married! I can’t argue with him.”

At this time, the friends approached Rutilov’s house and stopped at the gate.

“You can’t just barge in,” Peredonov said angrily.

“What an oddball, they’re waiting impatiently,” Rutilov exclaimed.

“But maybe I don’t want to.”

“Well, you don’t want to, you freak! What, are you going to live alone your whole life?” Rutilov confidently retorted. “Or are you going to a monastery? Or has Varvara not become disgusting to you yet? No, just think what a face she’ll make if you bring home a young wife.”

Peredonov gave a short, abrupt laugh, but immediately frowned and said:

“And maybe they don’t want to either.”

“Well, why wouldn’t they, you oddball!” Rutilov replied. “I give you my word.”

“They’re proud,” Peredonov invented.

“What do you care! Even better.”

“They’re mockers.”

“But not of you,” Rutilov persuaded.

“How do I know!”

“Well, just believe me, I won’t deceive you. They respect you. After all, you’re not some Pavlushka to be laughed at.”

“Yes, I believe you,” Peredonov said distrustfully. “No, I want to assure myself that they’re not laughing at me.”

“What an oddball,” Rutilov said in surprise, “but how dare they laugh? Well, how do you want to assure yourself, then?”

Peredonov thought and said:

“Let them come out onto the street right now.”

“Well, fine, that can be done,” Rutilov agreed.

“All three of them,” Peredonov continued.

“Okay, fine.”

“And let each one say how she will please me.”

“Why is that?” Rutilov asked in surprise.

“That’s how I’ll see what they want, otherwise you’ll lead me by the nose,” Peredonov explained.

“No one will lead you by the nose.”

“Maybe they want to make fun of me,” Peredonov reasoned, “but let them come out, and then if they want to laugh, I’ll laugh at them too.”

Rutilov thought, shifted his hat to the back of his head and then back to his forehead, and finally said:

“Well, wait, I’ll go tell them. What a miracle-worker! Just come into the yard for now, otherwise, someone else might walk down the street and see you.”

“I don’t care,” Peredonov said, but still followed Rutilov through the gate.

Rutilov went into the house to his sisters, and Peredonov remained waiting in the yard.

In the living room, a corner room facing the gate, sat all four sisters, all alike, all resembling their brother, all pretty, rosy-cheeked, cheerful: the married Larisa, calm, pleasant, plump; the fidgety and quick Darya, the tallest and thinnest of the sisters; the giggling Lyudmila; and Valeriya, small, delicate, fragile in appearance. They were enjoying nuts and raisins and, evidently, waiting for something, and therefore were more agitated and laughing more than usual, recalling the latest town gossip and ridiculing acquaintances and strangers.

They had been ready to go to the altar since morning. All that remained was to put on a suitable wedding dress and pin on the veil and flowers. The sisters did not mention Varvara in their conversations, as if she did not exist. But the mere fact that they, merciless mockers, picking apart everyone, did not utter a single word about Varvara all day long, proved that the awkward thought of her was stuck like a nail in each sister’s head.

“He’s here!” Rutilov announced, entering the living room, “He’s standing at the gate.”

The sisters rose excitedly and all at once began to talk and laugh.

“There’s just one snag,” Rutilov said, chuckling.

“What, what is it?” Darya asked. Valeriya frowned irritably with her beautiful, dark eyebrows.

“I don’t know if I should say?” Rutilov asked.

“Well, quickly, quickly!” Darya urged.

With some embarrassment, Rutilov related Peredonov’s desire. The young ladies shrieked and began to scold Peredonov, vying with each other. But gradually their indignant shouts were replaced by jokes and laughter. Darya made a glumly expectant face and said:

“That’s how he stands at the gate.” It came out similar and amusing.

The young ladies began to look out the window towards the gate. Darya slightly opened the window and shouted:

“Ardalyon Borysyich, can one say it from the window?”

A grim voice was heard:

“No.”

Darya hastily slammed the window shut. The sisters burst into ringing and uncontrollable laughter and ran from the living room to the dining room so Peredonov wouldn’t hear them. In this cheerful family, they knew how to transition from the angriest mood to laughter and jokes, and a cheerful word often settled matters.

Peredonov stood and waited. He was sad and afraid. He thought of running away, but he didn’t dare do that either. Music was heard from somewhere far away: probably the marshal’s daughter was playing the piano. Faint, tender sounds flowed through the quiet, dark evening air, inducing sadness, giving rise to sweet dreams.

Initially, Peredonov’s dreams took an erotic turn. He imagined the Rutilov young ladies in the most seductive positions. But the longer the wait continued, the more irritated Peredonov became—why were they making him wait? And the music, barely touching his deadened, crude feelings, died for him.

And around him, night descended, quiet, rustling with ominous approaches and whispers. And everywhere seemed even darker because Peredonov stood in a space illuminated by a lamp in the living room, the light from which fell in two strips onto the yard, widening towards the neighbor’s fence, beyond which dark log walls were visible. In the depths of the yard, the trees of Rutilov’s garden darkened suspiciously and whispered about something. On the streets, somewhere nearby, slow, heavy footsteps were heard for a long time on the boardwalks. Peredonov began to fear that while he stood there, he would be attacked and robbed, or even killed. He pressed himself against the very wall, into the shadow, so as not to be seen, and waited timidly.

But then long shadows ran across the illuminated strips in the yard, doors slammed, and voices were heard beyond the door on the porch. Peredonov brightened. “They’re coming!” he thought joyfully, and pleasant dreams of the beautiful sisters lazily stirred in his head again—the wretched offspring of his meager imagination.

The sisters stood in the hallway. Rutilov went out into the yard to the gate and looked around, to see if anyone was coming down the street.

No one was seen or heard.

“No one’s here,” he said in a loud whisper to his sisters, cupping his hands.

He remained on guard in the street. Peredonov also went out into the street with him.

“Well, now they’ll tell you,” Rutilov said.

Peredonov stood right by the gate and looked through the crack between the gate and the gatepost. His face was grim and almost frightened, and all dreams and thoughts had died in his head and were replaced by a heavy, objectless lust.

Darya was the first to approach the slightly ajar gate.

“Well, how can I please you?” she asked.

Peredonov remained grimly silent. Darya said:

“I will bake you delicious pancakes, hot ones, just don’t choke.”

Lyudmila, from behind her shoulder, cried:

“And every morning I’ll walk around the town, collect all the gossip, and then tell you. It’ll be great fun.”

Between the cheerful faces of the two sisters, Valerochka’s capricious, thin face appeared for a moment, and her fragile voice was heard:

“And I will never tell you how I’ll please you—guess for yourself.”

The sisters ran off, bursting into laughter. Their voices and laughter died down behind the doors. Peredonov turned away from the gate. He was not entirely satisfied. He thought: they blurted something out and left. They should have given me notes instead. But it was too late to stand there and wait.

“Well, did you see?” Rutilov asked. “Which one for you?”

Peredonov fell into thought. Of course, he finally realized, he should choose the youngest one. Why would he marry an old maid!

“Bring Valeriya,” he said decisively.

Rutilov went home, and Peredonov again entered the yard.

Lyudmila peeked stealthily through the window, trying to hear what was being said, but heard nothing. Then footsteps sounded on the boardwalk in the yard. The sisters quieted down and sat agitated and embarrassed. Rutilov entered and announced:

“He chose Valeriya. She’s waiting,” he said, “standing at the gate.”

The sisters made a noise, laughed. Valeriya paled slightly.

“There, there,” she repeated, “I really want to, I really need to.”

Her hands trembled. They began to dress her – all three sisters fussed around her. She, as always, minced and lingered. Her sisters hurried her. Rutilov chattered tirelessly, joyfully and excitedly. He liked that he had arranged all this so cleverly.

“Did you get the cabs ready?” Darya asked, concerned.

Rutilov replied with vexation:

“How could I? The whole town would have gathered. Varvara would have dragged him back by his hair.”

“So how will we manage?”

“Like this: we’ll walk to the square in pairs, and hire them there. Very simple. First you with the bride, and Larisa with the groom – and not right away, lest someone in town see. And I’ll pick up Falastov with Lyudmila, they’ll go together, and I’ll also grab Volodin.”

Peredonov, left alone, sank into sweet dreams. He dreamed of Valeriya in the enchantment of the wedding night, undressed, modest, but cheerful. All thin and delicate.

He dreamed, while at the same time pulling stray caramels from his pocket and sucking on them.

Then it occurred to him that Valeriya was a coquette. She, he thought, would demand clothes and furnishings. Then, perhaps, he would have to not only not save money each month, but also spend what he had accumulated. And his wife would become finicky, and perhaps wouldn’t even look after the kitchen. And they might even put poison in his food in the kitchen – Varvara, out of spite, would bribe the cook. “And in general,” Peredonov thought, “Valeriya is too delicate a thing. You wouldn’t know how to approach her. How would you scold her? How would you shove her? How would you spit on her? She’d cry her eyes out, shame him all over town. No, it’s scary to get involved with her. Lyudmila, on the other hand, is simpler. Should he take her?”

Peredonov went to the window and tapped on the frame with his stick. Half a minute later, Rutilov poked his head out the window.

“What do you want?” he asked with concern.

“Changed my mind,” Peredonov grumbled.

“What!” Rutilov cried, startled.

“Bring Lyudmila,” Peredonov said.

Rutilov withdrew from the window.

“That bespectacled devil,” he muttered and went to his sisters.

Valeriya was delighted.

“Your luck, Lyudmila,” she said cheerfully.

Lyudmila began to laugh — she fell into an armchair, leaned back, and laughed and laughed.

“What should I tell him?” Rutilov asked, “Is she agreed?”

Lyudmila couldn’t say a word from laughing and just waved her hands.

“Yes, she’s agreed, of course,” Darya said for her. “Tell him quickly, otherwise he’ll leave foolishly, won’t wait.”

Rutilov went into the living room and said in a whisper through the window:

“Wait, she’ll be ready soon.”

“Be quicker,” Peredonov said angrily, “what are they dawdling for!”

Lyudmila was dressed quickly. In about five minutes, she was completely ready.

Peredonov thought about her. She was cheerful, sweet-natured. But she laughed too much. She might laugh at him, he thought. Scary. Darya, though lively, was still more sedate and quieter. And beautiful too. Better to take her. He knocked on the window again.

“He’s knocking again,” Larisa said, “is he looking for you, Darya?”

“That devil!” Rutilov cursed and ran to the window.

“What now?” he asked in an angry whisper, “Changed your mind again?”

“Bring Darya,” Peredonov replied.

“Well, wait,” Rutilov whispered fiercely.

Peredonov stood and thought about Darya — and again, his brief admiration for her in his imagination was replaced by fear. She was too quick and bold. She’d overwhelm him. And why stand here and wait? he thought: you’ll catch a cold. In the ditch on the street, in the grass under the fence, maybe someone is hiding, they might suddenly jump out and kill him. And Peredonov became melancholic. After all, they were dowerless, he thought. They had no connections in the educational department. Varvara would complain to the princess. And the director was already holding a grudge against Peredonov anyway.

Peredonov became annoyed with himself. Why was he getting entangled with Rutilov here? As if Rutilov had bewitched him. Yes, perhaps he really had bewitched him. He needed to ward off the evil spell quickly.

Peredonov spun around, spat in all directions, and mumbled:

“Chur-churashki, churki-bolvashki, buki-bukashki, vedi-tarakaashki. Chur me. Chur me. Chur, chur, chur. Chur-perechur-raschur.”(This is a Russian proverb that wards off evil spirits. Translator’s note.)

His face showed strict attention, as during the performance of an important ritual. And after this necessary action, he felt safe from Rutilov’s obsession. He decisively tapped on the window with his stick, muttering angrily:

“I should report them—they’re luring me in. No, I don’t want to get married today,” he announced to Rutilov, who had poked his head out.

“But Ardalyon Borysyich, everything’s already ready,” Rutilov tried to persuade.

“I don’t want to,” Peredonov said decisively, “let’s go to my place and play cards.”

“That devil!” Rutilov cursed. “He doesn’t want to get married, he’s scared,” he announced to his sisters. “But I’ll still talk the fool into it. He’s inviting me to his place to play cards.”

The sisters all cried out at once, scolding Peredonov.

“And you’re going to that scoundrel?” Valeriya asked with vexation.

“Well, yes, I’ll go and collect a fine from him. And he won’t get away from us yet,” Rutilov said, trying to maintain a confident tone, but feeling very awkward.

The vexation with Peredonov quickly turned into laughter for the young ladies. Rutilov left. The sisters ran to the windows.

“Ardalyon Borysyich!” Darya cried, “Why are you so indecisive? This won’t do.”

“Sourpuss Sourpuss-ovich!” Lyudmila cried with laughter.

Peredonov became annoyed. In his opinion, the sisters should have been crying from sorrow that he had rejected them. “They’re pretending!” he thought, silently leaving the yard. The young ladies ran to the street-facing windows and shouted mocking words after Peredonov until he disappeared into the darkness.

V

Peredonov was consumed by melancholy. There were no more caramels in his pocket, which saddened and annoyed him. Rutilov spoke almost the entire way alone, continuing to praise his sisters. Peredonov only once joined the conversation. He angrily asked:

“Does a bull have horns?”

“Well, yes, so what?” said a surprised Rutilov.

“Well, I don’t want to be a bull,” Peredonov explained.

An annoyed Rutilov said:

“You, Ardalyon Borysyich, will never be a bull, because you are a complete pig.”

“You’re lying!” Peredonov said grimly.

“No, I’m not lying, and I can prove it,” Rutilov said gleefully.

“Prove it,” Peredonov demanded.

“Wait, I’ll prove it,” Rutilov replied with the same malicious glee in his voice.

Both fell silent. Peredonov waited timidly, consumed by anger towards Rutilov. Suddenly Rutilov asked:

“Ardalyon Borysyich, do you have a snout?”

“Yes, but I won’t give it to you,” Peredonov replied maliciously.

Rutilov burst out laughing.

“If you have a snout, then how are you not a pig!” he cried joyfully.

Peredonov, horrified, clutched his nose.

“You’re lying, what snout do I have, I have a human face,” he mumbled.

Rutilov laughed. Peredonov, looking angrily and timidly at Rutilov, said:

“You deliberately led me astray with that ‘stupefying’ talk today and stupefied me to marry me off to your sisters. One witch isn’t enough, to marry three at once!”

“Freak, how come I wasn’t stupefied?” Rutilov asked.