The Master and Margarita: What Inspired Bulgakov

Goethe’s Faust, the Brockhaus and Efron Dictionary, a biography of Jesus Christ, a study by a Swiss neuropathologist—we explain how these and other texts helped Mikhail Bulgakov in his work on the great novel.

On our website you can buy this book via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

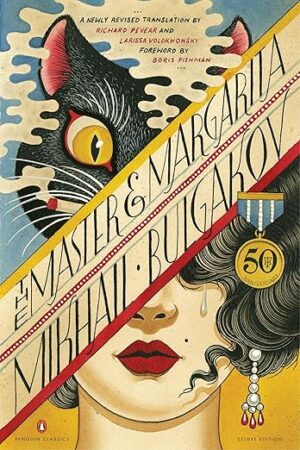

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

Page Count: 448Year: 1967Products search Imagine 1930s Moscow — a city constrained by bureaucracy, shortages, and state-enforced atheism — is suddenly visited by Satan himself, in the guise of Professor Woland, accompanied by his infernal retinue, including the absurdly dressed Koroviev and the massive, talking cat Behemoth. Woland’s visit is a devilish inspection and a session of black […]

€11.00 Login to Wishlist

Mikhail Bulgakov worked on the novel The Master and Margarita for twelve years: from 1928 until February 1940, in several stages, with breaks and in parallel with other texts. The range of the writer’s reading and bibliographic interests can be reconstructed thanks to the recollections of his contemporaries and the research of his biographers. The literature Bulgakov used can also be discerned from the various editions of the novel preserved in the writer’s archive. It is impossible to present the entire list of literature that might have influenced Bulgakov and his novel, so we will discuss some of the sources for his book.

1. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Faust

Bulgakov’s novel has a huge number of layers, and the Faustian is arguably the most recognizable. Allusions to Faust permeate the entire text—from the epigraph, which poses a philosophical question about light and darkness, to the characters’ images, direct quotes, parodic scenes, and so on. The writer’s library contained a 1902 edition published in St. Petersburg, translated and annotated by Alexander Sokolovsky. However, he knew Goethe’s text not only from the book but also from Charles Gounod’s opera of the same name. The writer’s sister, Nadezhda Zemskaya, recalled that in Kyiv, Bulgakov saw the opera Faust 41 times. The writer’s first wife, Tatyana Nikolaevna Lappa, recalled to Marietta Chudakova that Bulgakov “loved Faust most of all and most often sang ‘Upon the Earth the Entire Human Race’ and Valentin’s aria—’I pray for thee, my sister…'” And here is the recollection of theater critic Vitaly Vilenkin: “I really liked the whole atmosphere of the small apartment: antique furniture, cozy table lamps, an open grand piano with Faust on the music stand, flowers.” The writer’s third wife, Elena Sergeevna, told literary scholar Vladimir Lakshin how Bulgakov, “pacing the room, under the impression of a newspaper article he had just read, would sometimes hum to the tune of Faust: ‘He is a reviewer… kill him!'”

The Epigraph

…so who are you, after all? — I am part of that power which eternally wills evil and eternally works good.

The epigraph from the first part of Faust first appeared in the typewritten edition of 1938. Researchers suggest that the writer translated this fragment himself. In the 1902 edition, Mephistopheles, explaining the essence of his nature, says: “I am part of that darkness from which light was born… Light can only cling to the corporeal. It originates from the corporeal, and the corporeal makes it beautiful. But the corporeal can also block its path.” Judging by everything, these words made their way into the dialogue between Woland and Levi Matvey in Chapter 29: “…What would your goodness do if evil did not exist, and how would the earth look if shadows disappeared from it?”

Woland

In choosing a name for the hero, Bulgakov considered several options: Antesser, Velyar Velyarovich, and in one of the drafts, the black magician’s business card reads “Doctor Theodor Woland.” Woland is also from Faust: in the scene “Walpurgis Night,” Mephistopheles addresses the representatives of the evil spirits and demands they make way for Junker Voland. Both in Goethe’s tragedy and Bulgakov’s novel, the devil first appears during a conversation between a teacher and a student. Mephistopheles, in the guise of a black poodle, appears during the walk of Faust and Wagner; Woland sits down on the bench with Berlioz and Homeless at the Patriarch’s Ponds. The namesake of the head of MASSOLIT—the composer Hector Berlioz—wrote Eight Scenes from ‘Faust’ in 1829, which were later included in his opera The Damnation of Faust.

The Black Poodle

In Goethe, Mephistopheles, wishing to enter Faust’s house, as already mentioned, takes the form of a black poodle. In the scene at the Patriarch’s Ponds, Woland appears with a cane topped with a poodle’s head, and Margarita at Satan’s ball wears a “heavy image of a poodle in an oval frame on a heavy chain.” And finally, in early drafts of the novel from the late twenties, Ivanushka escaped from the psychiatric hospital after turning into a huge black poodle.

Faust and Margarita

In September 1933, in one of the notebooks with sketches for the novel, Bulgakov wrote: “The Poet’s Meeting with Woland. Margarita and Faust.” The Master is not yet in the text, but there is a hero whom the author calls the Poet and Faust. He will later become the Master, and the comparison with Faust will remain: “Surely you don’t want, like Faust, to sit over a retort in the hope that you will manage to mold a new homunculus?” Woland asks him. Margarita’s name is derived from Gretchen, Faust’s beloved (in the Western European tradition, “Gretchen” is a diminutive of “Margarita”). Both are similar in the selfless love they feel for the Master and Faust.

Goethe and Gounod at Satan’s Ball

In early drafts, Goethe himself and the composer Charles Gounod were present at Satan’s ball: both bowed to Margarita but did not kiss her knee. The distinguished guests were noted with a special gift:

“A round golden tray appeared before Margarita, and on it were two small cases. Their lids sprang open, and the cases contained a golden laurel wreath each, which could be worn in a buttonhole like a medal.”

2. Alexander Chayanov. Venediktov, or the Memorable Events of My Life

Elena Bulgakova told Marietta Chudakova that Alexander Vladimirovich Chayanov’s book, presented by the artist Natalia Ushakova, was particularly interesting to her husband and “undoubtedly stimulated the ideas and plot developments of both The Master and Margarita and A Dead Man’s Memoirs.” “I say with full certainty that this short novel served as the genesis of the idea, the creative impulse for writing The Master and Margarita,” recalled his second wife, Lyubov Evgenievna Belozerskaya.

The novella tells about the devil’s stay in Moscow at the beginning of the 19th century, and the main character, named Bulgakov, must save his beloved, who has fallen under the influence of evil spirits.

Researchers note that the infernal theme also links Bulgakov’s novel with other works by his contemporaries: Alexander Grin’s Fandango, Ovadia Savich’s The Foreigner from No. 17, Emil Mindlin’s The Return of Doctor Faust, and others.

3. The Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary

In the notebook with materials for the novel, Bulgakov compiled several thematic blocks: “On God,” “On the Devil,” “Jesus Christ,” and others. In developing these themes, Bulgakov often uses the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedia and makes excerpts from the articles “Devil,” “Demon,” “Pontius Pilate,” “Centurion,” and “Jerusalem.” He also refers to the articles “God” and “Kant” (where several proofs of the existence of God are presented), “Sorcery” (the name Hella—the vampire from Woland’s retinue, as we remember—was used on the island of Lesbos for deceased girls who became vampires) and many others (Demonology, Demonomania, Witchcraft, Satan, Witches’ Sabbath). In developing Margarita’s image, the writer studied the article about Queen Margaret of Valois.

4. Mikhail Orlov. The History of Man’s Dealings with the Devil

From Orlov’s monograph, Bulgakov gleaned a number of details about otherworldly power (as well as about sorcerers, witches, and rituals) and various ideas about it. Thus, the image of the cat Behemoth may hark back to the biblical demon of the same name described by Orlov:

“His hands were of the human type, but his huge belly, short tail, and thick hind legs, like those of a hippopotamus, recalled the name he bore.”

Bulgakov’s character is “black, big as a hippopotamus.” Orlov also writes that the devil in human form can be betrayed by hands that resemble bird’s claws. Recall the nurse in Chapter 18: “I’ll take the money,” the nurse said in a man’s bass voice, “there’s no need for it to lie around here.” — She raked up the labels with a bird’s claw and began to melt into the air.” Bird’s claws also flash in the chapter “By the Candles“: before the ball, Margarita enters Woland’s room and sees there a “candelabrum with sockets in the form of clawed bird’s feet.” Telling what a Sabbath is, Orlov writes that one of the attributes of the devil’s mass is a dirty shirt: before the ball, Woland is dressed in a “long nightshirt, dirty and patched on the left shoulder.”

5. Ernest Renan. The Life of Jesus

While working on the image of Yeshua Ha-Notsri, Bulgakov studied literature on the history of Christianity: Henri Barbusse’s Jesus, Arthur Drews’ The Christ Myth, Frederic Farrar’s The Life of Jesus Christ, and David Strauss’s The Life of Jesus. Among others, the French philosopher and historian of religion Ernest Renan’s book, The Life of Jesus, attracted the writer’s attention. In early drafts of the novel, the well-read Berlioz, talking with Homeless at the Patriarch’s Ponds, mentions Renan in addition to the ancient historians Philo of Alexandria, Josephus Flavius, and Cornelius Tacitus.

The image of the Yershalaim Temple also goes back to Renan (“a block of marble with golden dragon scales instead of a roof”). Bulgakov copied from his book: “…Mount Moriah and the shining prospect of the temple terraces and roofs covered with shimmering scales,” “…at sunrise the sacred mountain shone dazzlingly and appeared as a block of snow and gold.”

Among the circumstances of Jesus’s arrest, Renan mentions a certain “legal trap“: wishing to hand over the “troublemaker” to the guard, the high priests “bribe two witnesses and hide them behind a partition; then they arrange to lure the accused into a room on the other side of the partition, where his words could be heard by the witnesses unseen by him. Two candles are lit next to him in order to unequivocally establish that the witnesses ‘saw him’.” And now let us recall the scene of Yeshua’s arrest in Bulgakov’s novel. The philosopher tells Pilate that the “kind and curious man” Judas invited him to his house:

“— He lit the lamps… — Pilate muttered through his teeth in the prisoner’s tone, and his eyes flickered. — Yes, — Yeshua continued, slightly surprised by the procurator’s awareness, — he asked me to express my view on state authority. This question interested him greatly.”

6. Demyan Bedny. The New Testament Without Flaw by Evangelist Demyan

A possible prototype for the young poet Ivan Nikolaevich Ponyryov, writing under the pseudonym Ivan Homeless (Ivan Bezdomny), was Yefim Alekseevich Pridvorov, better known as Demyan Bedny (Demyan the Poor). In the latter’s anti-religious poem titled The New Testament Without Flaw by Evangelist Demyan, Christian dogmas were satirically ridiculed. In the afterword, the “evangelist” reported:

“I insist that based on the Gospels, only such an image of Jesus can be given: a liar, a drunkard, a womanizer, etc. <…> There was neither a good nor a bad god. A figment of the imagination!“

Recall the first chapter of Bulgakov’s novel, in which Berlioz demands an anti-religious poem from Homeless, indicating that Jesus Christ did not exist. Bulgakov mentions Bedny in his diary, and newspaper clippings mentioning the poet are preserved in the archive.

The anti-religious propaganda of the 1920s, which caused Bulgakov sharp dislike, generally influenced the novel’s concept. On January 5, 1925, he wrote in his diary:

“The point is not in the sacrilege, although it is, of course, immense, if we talk about the external side. The point is in the idea, which can be proved factually: Jesus Christ is depicted as a scoundrel and a swindler, precisely him. <…> This crime is beyond measure.”

7. Auguste Forel. The Sexual Question. A Natural Scientific, Psychological, Hygienic, and Sociological Study for the Educated

In the notebooks with materials for the novel, Bulgakov mentions the book by the Swiss neuropathologist Auguste Forel, dedicated to questions of family and marriage, and notes two stories described in it: the case of Frieda Keller and the case of Koniecko. In talking about the pathology of female behavior, Forel gives the example of 19-year-old Frieda Keller: seduced by the owner of a café, she gave birth to a boy, and five years later, finding herself in difficult financial circumstances, she strangled the child with a cord. The other case described by Forel is the story of 19-year-old Koniecko from Silesia, who killed her newborn baby by stuffing a crumpled handkerchief into its mouth. These two cases from Forel’s study merge into the story of Frieda, whom Margarita meets at Satan’s ball:

“She worked in a café, the owner somehow lured her into the pantry, and nine months later she gave birth to a boy, carried him into the woods and stuffed a handkerchief into his mouth, and then buried the boy in the ground.”

Margarita saves Frieda by using the one wish given to her by Woland after the ball, and asks that they stop putting the handkerchief on her.

Sources

Belozerskaya-Bulgakova L. E. Memoirs. Moscow, 1990.

Bulgakov M. A. Collected Works. Moscow, 2007–2011.

Bulgakov M. A. The Master and Margarita. Complete Collection of Drafts of the Novel. Moscow, 2014.

Goethe J. W. Faust. St. Petersburg, 1902.

Zemskaya E. A. Mikhail Bulgakov and His Relatives. A Family Portrait. Moscow, 2004.

Lesskis G. A., Atarova K. N. Moscow — Yershalaim. A Guide to M. Bulgakov’s Novel “The Master and Margarita”. Moscow, 2014.

Orlov M. A. A History of Man’s Relations with the Devil. Moscow, 1991.

Renan E. The Life of Jesus. Moscow, 1990.

Chudakova M. O. A Biography of Mikhail Bulgakov. Moscow, 1988.

Yablokov E. A. Mikhail Bulgakov and World Culture: Reference Thesaurus. St. Petersburg, 2011.

Yablokov E. A. Chorus of Soloists: Problems and Heroes of Russian Literature of the First Half of the XX Century. St. Petersburg, 2014.

Memoirs about M. Bulgakov. Collection. Moscow, 1988.