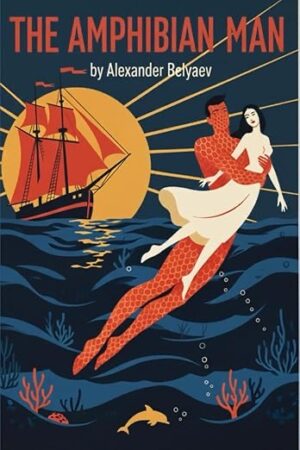

The Amphibian Man, Alexander Belyaev: Read FREE Full Text Online (English Translation)

You can now read the full text for free of the Soviet era’s most famous romantic science fiction adventure — The Amphibian Man by the iconic author Alexander Belyaev. This essential piece of reflective fiction Russian literature is available for online reading here in a high-quality English translation.

Dive into this captivating masterpiece and experience the tragic love story of Ichthyander, a young man surgically given shark gills, as he faces the greed and cruelty of human society in a South American setting. Start reading instantly without any download required. This exclusive free access is your gateway to the world of great Russian authors and their works.

You can also buy this book from us in the definitive paperback edition via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

The Amphibian Man by Alexander Belyaev

Page Count: 360Year: 1927READ FREEProducts search Meet Ichthyander, an enigmatic young man who has lived underwater since childhood, thanks to a mad scientist’s incredible experiment. With shark gills replacing his lungs, he’s destined to exist between two worlds: human and aquatic. But can Ichthyander truly find his place when he faces not only marine predators but also human greed, […]

€18.00 Login to Wishlist

First published in 1928 by

state publishing house “Gosizdat”

This book is in the public domain

Reprint by Publishing House №10

Publication date July 13, 2025

Translation from Russian

299 Pages, Font 12 pt, Bookman Old Style

Electronic edition, File size 933 KB

Cover design, Translate by Yulia Basharova

Copyright© Yulia Basharova 2025. All rights reserved

Table of Contents

PART ONE

The Girl and the Swarthy Man. 102

Battle with the Octopuses. 150

PART TWO

PART THREE

PART ONE

The Sea Devil

It was a sultry January night in the Argentinian summer. The black sky was covered in stars. The “Jellyfish” lay calmly at anchor. The silence of the night was unbroken by the splash of a wave or the creak of rigging. The ocean seemed to be in a deep sleep.

On the schooner’s deck, half-naked pearl divers lay. Exhausted by their work and the hot sun, they tossed and turned, sighed, and cried out in heavy slumber. Their arms and legs twitched nervously. Perhaps in their dreams, they saw their enemies – sharks. On these hot, windless days, the men were so tired that, after the catch, they couldn’t even pull the boats onto the deck. Besides, it wasn’t necessary: nothing foretold a change in the weather. And so the boats remained on the water overnight, tied to the anchor chain. The yards were not squared, the rigging poorly tightened, and the uncleared jib shuddered slightly with the faintest breath of wind. The entire deck between the forecastle and the poop was cluttered with heaps of pearl oyster shells, fragments of coral limestone, ropes the divers used to descend to the bottom, canvas bags where they put the collected shells, and empty barrels. Near the mizzenmast stood a large barrel of fresh water with an iron dipper on a chain. Around the barrel on the deck was a dark stain from spilled water.

From time to time, one or another diver would rise, swaying in a half-sleep, and stepping on the arms and legs of the sleeping men, would stumble towards the water barrel. Without opening his eyes, he would drink a dipper of water and collapse wherever he landed, as if he had drunk not water but pure alcohol. The divers were tormented by thirst: it was dangerous to eat in the morning before work – a person experiences too much pressure in the water – so they worked all day on an empty stomach until it became dark in the water, and only before sleep could they eat, and they were fed salted meat.

At night, the Indian Balthazar was on watch. He was the closest assistant to Captain Pedro Zurita, owner of the schooner “Jellyfish.”

In his youth, Balthazar was a renowned pearl diver: he could stay underwater for ninety and even a hundred seconds – twice the usual time.

“Why? Because in our time, they knew how to teach, and they started training us from childhood,” Balthazar used to tell young pearl divers. “I was just a boy, about ten years old, when my father sent me to apprentice on a tender with Jose. He had twelve boy apprentices. He taught us like this: he’d throw a white stone or a shell into the water and order, ‘Dive, get it!’ And each time he’d throw it deeper and deeper. If you didn’t get it, he’d whip you with a line or a rope and throw you into the water like a puppy. ‘Dive again!’ That’s how he taught us to dive. Then he started accustoming us to staying underwater longer. An old experienced diver would go to the bottom and tie a basket or net to the anchor. And then we’d dive and untie it underwater. And until you untied it, you weren’t to surface. And if you surfaced, you’d get the whip or the line.

They beat us mercilessly. Not many endured. But I became the best diver in the entire district. I earned well.”

Having grown old, Balthazar abandoned the dangerous trade of a pearl seeker. His left leg was disfigured by a shark’s teeth, and his side was torn by an anchor chain. He owned a small shop in Buenos Aires and traded in pearls, corals, shells, and sea rarities. But on shore, he was bored, and so he often went on pearl fishing expeditions. The industrialists valued him. No one knew the La Plata Gulf, its shores, and the places where pearl oysters lived better than Balthazar. The divers respected him. He knew how to please everyone – both the divers and the owners.

He taught young divers all the secrets of the trade: how to hold their breath, how to ward off shark attacks, and, when it was opportune, how to hide a rare pearl from the owner.

The industrialists, the schooner owners, knew and valued him because he could accurately assess pearls with a single glance and quickly select the best ones for the owner.

Therefore, industrialists readily took him with them as an assistant and advisor.

Balthazar sat on a barrel, slowly smoking a thick cigar. The light from the lantern attached to the mast fell on his face. It was elongated, not high-cheekboned, with a regular nose and large, beautiful eyes – the face of an Araucanian. Balthazar’s eyelids dropped heavily and slowly rose. He was dozing. But if his eyes slept, his ears did not. They were awake and warned of danger even during deep sleep. But now Balthazar heard only the sighs and murmuring of the sleeping men. From the shore came the smell of decaying pearl mollusks – they were left to rot to make it easier to extract the pearls: the shell of a living mollusk is not easy to open. This smell would have seemed repulsive to an unaccustomed person, but Balthazar inhaled it with pleasure. To him, a wanderer, a pearl seeker, this smell reminded him of the joys of a free life and the exciting dangers of the sea.

After the pearls were extracted, the largest shells were transferred to the “Jellyfish.”

Zurita was shrewd: he sold the shells to a factory where they made buttons and cufflinks from them.

Balthazar was sleeping. Soon, the cigar fell from his weakened fingers. His head slumped onto his chest.

But then some sound reached his consciousness, coming from far out in the ocean. The sound repeated closer. Balthazar opened his eyes. It seemed as if someone was blowing a horn, and then a cheerful young human voice cried out: “Ah!” – and then an octave higher: “Ah-ah!..”

The musical sound of the horn was not like the sharp sound of a steamboat siren, and the cheerful exclamation did not at all resemble the cry for help of a drowning person. It was something new, unknown. Balthazar rose; it seemed to him as if the air had suddenly freshened. He went to the railing and keenly surveyed the ocean’s surface. Deserted. Silent. Balthazar nudged a sleeping Indian on the deck with his foot, and when the man rose, he quietly said:

“It’s crying. It’s probably him.”

“I don’t hear anything,” the Huron Indian replied just as quietly, kneeling and listening. And suddenly, the silence was again broken by the sound of the horn and the cry:

“Ah-ah!..”

The Huron, hearing this sound, crouched as if under a whip.

“Yes, it’s probably him,” the Huron said, his teeth chattering with fear. Other divers also woke up. They crawled towards the lantern-lit area, as if seeking protection from the darkness in the weak rays of yellowish light. They all sat huddled together, listening intently. The sound of the horn and the voice were heard once more in the distance, and then everything fell silent.

“It’s him…”

“The sea devil,” the fishermen whispered.

“We can’t stay here any longer!”

“It’s scarier than a shark!”

“Call the owner here!”

The slapping of bare feet was heard. Yawning and scratching his hairy chest, the owner, Pedro Zurita, emerged onto the deck. He was shirtless, wearing only canvas trousers; a revolver holster hung from his wide leather belt. Zurita approached the men. The lantern lit up his sleepy face, bronzed by the sun, his thick curly hair falling in strands over his forehead, black eyebrows, bushy, upturned mustache, and a small, grizzled beard.

“What happened?”

His rough, calm voice and confident movements reassured the Indians.

They all spoke at once. Balthazar raised his hand as a sign for them to be silent and said:

“We heard his voice… the sea devil’s.”

“You imagined it!” Pedro replied sleepily, his head dropping to his chest.

“No, we didn’t imagine it. We all heard ‘ah-ah!…’ and the sound of a horn!” the fishermen cried out.

Balthazar silenced them with the same hand gesture and continued:

“I heard it myself. Only the devil can make such a sound. No one at sea cries or blows a horn like that. We need to leave here quickly.”

“Fairy tales,” Pedro Zurita replied just as sluggishly.

He didn’t want to bring the still-rotting, foul-smelling shells from the shore onto the schooner or weigh anchor.

But he couldn’t persuade the Indians. They were agitated, waving their arms and shouting, threatening that they would go ashore tomorrow and walk to Buenos Aires if Zurita didn’t raise the anchor.

“Damn this sea devil along with you! Alright. We’ll raise anchor at dawn.” And, continuing to grumble, the captain went to his cabin.

He no longer felt like sleeping. He lit a lamp, lit a cigar, and began to pace back and forth in the small cabin. He thought about the incomprehensible creature that had recently appeared in these waters, scaring fishermen and coastal residents.

No one had yet seen this monster, but it had made its presence known several times. Legends were made about it. Sailors told them in whispers, looking around fearfully, as if afraid that this monster might overhear them.

This creature harmed some and unexpectedly helped others. “It’s a sea god,” old Indians would say, “it emerges from the depths of the ocean once every millennium to restore justice on earth.”

Catholic priests assured superstitious Spaniards that it was “the sea devil.” It had begun appearing to people because the populace was forgetting the holy Catholic church.

All these rumors, passed by word of mouth, reached Buenos Aires. For several weeks, “the sea devil” was the favorite topic of chroniclers and feuilletonists in tabloid newspapers. If schooners or fishing boats sank under unknown circumstances, or fishing nets were damaged, or caught fish disappeared, “the sea devil” was blamed. But others said that “the devil” sometimes threw large fish into fishermen’s boats and once even saved a drowning man.

At least one drowning man claimed that as he was sinking into the water, someone grabbed him from below by the back and, supporting him in this way, swam to shore, disappearing into the breaking waves the moment the rescued man stepped onto the sand.

But the most surprising thing was that no one had actually seen “the devil” itself. No one could describe what this mysterious creature looked like. Of course, there were eyewitnesses – they endowed “the devil” with a horned head, a goat’s beard, lion’s paws, and a fish tail, or depicted it as a giant horned toad with human legs.

Government officials in Buenos Aires initially paid no attention to these stories and newspaper articles, considering them idle fiction.

But the unrest – mainly among fishermen – intensified. Many fishermen hesitated to go out to sea. Catches decreased, and residents felt a shortage of fish. Then the local authorities decided to investigate this story. Several police coast guard steam launches and motorboats were sent along the coast with orders to “detain the unknown individual sowing discord and panic among the coastal population.” The police scoured the La Plata Gulf and the coast for two weeks, detaining several Indians as malicious spreaders of false, alarming rumors, but “the devil” was elusive.

The police chief published an official statement declaring that no “devil” existed, that it was all just fabrications of ignorant people who had already been detained and would receive due punishment, and urged fishermen not to trust rumors and to resume fishing.

For a time, this helped. However, “the devil’s” tricks did not cease.

One night, fishermen who were quite far from shore were awakened by the bleating of a kid goat, which had miraculously appeared on their bark. Other fishermen found their pulled-up nets cut.

Delighted by the new appearance of “the devil,” journalists now awaited explanations from scientists.

The scientists did not make them wait long.

Some believed that an unknown marine monster, capable of human-like actions, could not exist in the ocean. “It would be different,” scientists wrote, “if such a creature appeared in the little-explored depths of the ocean.” But scientists still could not allow that such a creature could act rationally. Scientists, along with the head of the maritime police, believed that it was all the antics of some prankster.

But not all scientists thought this way.

Other scientists referred to the famous Swiss naturalist Konrad Gessner, who described a sea maiden, a sea devil, a sea monk, and a sea bishop.

“After all, much of what ancient and medieval scholars wrote has been confirmed, despite the fact that modern science did not recognize these old teachings. Divine creation is inexhaustible, and for us, scientists, modesty and caution in our conclusions are more appropriate than for anyone else,” wrote some older scientists.

However, it was difficult to call these modest and cautious people scientists. They believed in miracles more than in science, and their lectures resembled sermons. Eventually, to resolve the dispute, a scientific expedition was dispatched. The members of the expedition were not fortunate enough to meet “the devil.” Instead, they learned much new about the actions of the “unknown person” (the old scientists insisted that the word “person” be replaced by the word “creature”).

In a report published in newspapers, the expedition members wrote:

“1. In some places on sandy shoals, we observed traces of narrow human footprints. The tracks came from the sea and led back to the sea. However, such tracks could have been left by a person who came to shore by boat.

- The nets we examined had cuts that could have been made by a sharp cutting instrument. It is possible that the nets caught on sharp underwater rocks or iron debris from sunken ships and tore.

- According to eyewitnesses, a dolphin, washed ashore by a storm a considerable distance from the water, was dragged back into the water by someone during the night. Footprints and what appeared to be long claw marks were found on the sand. It is likely that some compassionate fisherman dragged the dolphin back into the sea.

It is known that dolphins, while hunting for fish, help fishermen by herding fish towards the shallows. Fishermen, in turn, often rescue dolphins from distress. The claw marks could have been made by human fingers. Imagination gave the marks the appearance of claws.

- The kid goat could have been brought on a boat and left by some prankster.”

Scientists found other, equally simple, reasons to explain the origin of the traces left by “the devil.”

Scientists concluded that no sea monster could perform such complex actions.

Yet, these explanations did not satisfy everyone. Even among the scientists themselves, there were those for whom these explanations seemed doubtful. How could the most agile and persistent prankster carry out such things without being seen by people for so long? But the main thing the scientists omitted in their report was that “the devil,” as it was established, performed its feats within a short period in various, widely separated locations. Either “the devil” could swim with unheard-of speed, or it had some special devices, or finally, “the devil” was not one, but several. But then all these tricks became even more incomprehensible and threatening.

Pedro Zurita recalled this whole mysterious story, pacing incessantly in his cabin. He didn’t notice dawn breaking, and a pink ray entered through the porthole. Pedro extinguished the lamp and began to wash himself. As he poured warm water over his head, he heard frightened shouts coming from the deck. Zurita, without finishing his washing, quickly climbed the ladder.

The naked divers, with canvas wraps around their hips, stood by the railing, waving their arms and shouting chaotically. Pedro looked down and saw that the boats, left on the water overnight, were untied. The night breeze had carried them quite far into the open ocean. Now the morning breeze was slowly carrying them towards the shore. The oars of the skiffs, scattered on the water, floated in the bay.

Zurita ordered the divers to gather the boats. But no one dared to leave the deck. Zurita repeated the order.

“Go into the devil’s claws yourself,” someone retorted.

Zurita reached for his revolver holster. The crowd of divers backed away and huddled by the mast. The divers looked at Zurita with hostility. A confrontation seemed inevitable. But then Balthazar intervened.

“An Araucanian fears no one,” he said. “The shark didn’t finish me, and the devil will choke on old bones.” And, clasping his hands over his head, he threw himself from the railing into the water and swam towards the nearest boat.

Now the divers came to the railing and watched Balthazar with fear. Despite his age and bad leg, he swam excellently. In a few strokes, the Indian reached the boat, retrieved a floating oar, and climbed into the boat.

“The rope was cut with a knife,” he shouted, “and cut well! The knife was sharp as a razor.”

Seeing that nothing terrible had happened to Balthazar, several divers followed his example.

Riding a Dolphin

The sun had just risen, but it was already beating down mercilessly. The silvery-blue sky was cloudless, the ocean still. The “Jellyfish” was already twenty kilometers south of Buenos Aires. On Balthazar’s advice, the anchor was dropped in a small bay, near a rocky shore that rose from the water in two tiers.

The boats scattered across the bay. On each boat, as was customary, there were two divers: one dived, the other pulled the diver up. Then they switched roles.

One boat approached the shore quite closely. The diver gripped a large piece of coral limestone, tied to the end of a rope, with his legs and quickly descended to the bottom.

The water was very warm and transparent – every stone on the seabed was clearly visible. Closer to the shore, corals rose from the bottom – motionless, solidified bushes of underwater gardens. Small fish, shimmering with gold and silver, darted between these bushes.

The diver reached the bottom and, bending down, began to quickly gather shells and place them in a small bag tied to a strap at his side. His working partner, a Huron Indian, held the end of the rope and, leaning over the side of the boat, looked into the water.

Suddenly, he saw the diver jump to his feet as quickly as he could, wave his arms, grab the rope, and pull it so hard that he almost pulled the Huron into the water. The boat rocked. The Huron Indian hurriedly pulled his comrade up and helped him climb into the boat. The diver, with his mouth wide open, was breathing heavily, his eyes wide. His dark bronze face had turned gray – he was so pale.

“Shark?”

But the diver couldn’t answer anything; he fell to the bottom of the boat.

What could have frightened him so much at the bottom of the sea? The Huron bent down and began to peer into the water. Yes, something was wrong there. Small fish, like birds spotting a kite, hurried to hide in the dense thickets of underwater forests.

And suddenly, the Huron Indian saw something like crimson smoke appear from behind a protruding underwater rock. The smoke slowly spread in all directions, coloring the water pink. And then something dark appeared. It was the body of a shark. It slowly turned and disappeared behind the rock outcrop. The crimson underwater smoke could only be blood spilled on the ocean floor. What happened there? The Huron looked at his comrade, but he lay motionless on his back, gasping for air with his mouth wide open and staring blankly at the sky. The Indian grabbed the oars and hurried to take his suddenly ill comrade aboard the “Jellyfish.”

Finally, the diver came to his senses, but it was as if he had lost the power of speech – he only grunted, shook his head, and puffed out his lips.

The divers on the schooner surrounded the diver, eagerly awaiting his explanation.

“Speak!” a young Indian finally shouted, shaking the diver. “Speak, unless you want your cowardly soul to fly out of your body!” The diver shook his head and said in a muffled voice:

“I saw… the sea devil.”

“Him?”

“Come on, speak, speak!” the divers cried impatiently.

“I see a shark. A shark is swimming right at me. This is the end for me! Big, black, already opened its mouth, about to eat me. I look – something else is swimming…”

“Another shark?”

“The devil!”

“What’s he like? Does he have a head?”

“A head? Yes, I think so. Eyes like glasses.”

“If it has eyes, it must have a head,” the young Indian confidently declared. “Eyes are attached to something. And does it have paws?”

“Paws like a frog’s. Long, green fingers with claws and webs. It shines itself, like a fish with scales. It swam to the shark, flashed its paw – zap! Blood from the shark’s belly…”

“And what about its legs?” one of the divers asked.

“Legs?” the diver tried to recall. “No legs at all. There’s a big tail. And at the end of the tail, two snakes.”

“Who were you more afraid of — the shark or the monster?”

“The monster,” he answered without hesitation. “The monster, even though it saved my life. It was him…”

“Yes, it was him.”

“The sea devil,” the Indian said.

“The sea god who comes to the aid of the poor,” an old Indian corrected. This news quickly spread among the boats in the bay. The divers rushed back to the schooner and pulled their boats aboard.

Everyone crowded around the diver, saved by “the sea devil.” And he repeated that red flames shot from the monster’s nostrils, and its teeth were sharp and long, the size of a finger. Its ears moved, it had fins on its sides, and a tail at the back, like an oar.

Pedro Zurita, stripped to the waist, in short white trousers, barefoot in slippers, and with a tall, wide-brimmed straw hat on his head, shuffled across the deck, listening to the conversations.

The more engrossed the storyteller became, the more Pedro was convinced that it was all fabricated by the diver, who had been frightened by the approaching shark.

“However, maybe not everything is made up. Someone did cut open the shark’s belly: the water in the bay turned pink, after all. The Indian is lying, but there’s some truth to all of this. A strange story, damn it!”

Here, Zurita’s thoughts were interrupted by the sound of a horn, suddenly echoing from behind the rock.

This sound struck the crew of the “Jellyfish” like a clap of thunder. All conversations ceased at once, faces paled. The divers stared with superstitious dread at the rock from which the horn sound had emanated.

Not far from the rock, a pod of dolphins played on the ocean’s surface. One dolphin separated from the pod, snorted loudly, as if answering the horn’s call, swam quickly towards the rock, and disappeared behind the cliffs. A few more moments of tense anticipation passed. Suddenly, the divers saw a dolphin emerge from behind the rock. On its back sat, as if on a horse, a strange creature – “the devil” the diver had just spoken of. The monster had the body of a human, and on its face were enormous eyes, like old pocket watches, gleaming in the sun’s rays like car headlights. Its skin shimmered with a delicate blue-silver, and its hands resembled those of a frog – dark green, with long fingers and webbing between them. Its legs below the knees were in the water. Whether they ended in tails, or were ordinary human legs, remained unknown. The strange creature held a long, twisted conch shell in its hand. It blew into the shell once more, laughed a cheerful human laugh, and then suddenly cried out in pure Spanish:

“Faster, Liding, forward!” It patted the dolphin’s glossy back with its froglike hand and spurred its sides with its feet. And the dolphin, like a good horse, increased its speed.

The divers involuntarily cried out.

The unusual rider turned around. Seeing the humans, it slid off the dolphin with the speed of a lizard and disappeared behind its body. A green hand appeared from behind the dolphin’s back, striking the animal’s back. The obedient dolphin submerged with the monster.

The strange pair made a semicircle underwater and disappeared behind the submerged rock…

This entire unusual appearance lasted no more than a minute, but the spectators were long unable to recover from their astonishment.

The divers shouted, ran around the deck, and clutched their heads. The Indians fell to their knees and begged the sea god to spare them. A young Mexican, terrified, climbed the mainmast and screamed. The Black sailors scurried into the hold and huddled in a corner.

Thinking about diving was out of the question. Pedro and Balthazar with difficulty restored order. The “Jellyfish” weighed anchor and headed north.

Zurita’s Failure

The captain of the “Jellyfish” went down to his cabin to think about what had happened.

“I could go mad!” Zurita muttered, pouring a pitcher of warm water over his head. “A sea monster speaking the purest Castilian dialect! What is this? Devilry? Madness? But madness can’t suddenly seize the entire crew. Not even an identical dream can be dreamed by two people. But we all saw the sea devil. That’s undeniable. So, he really does exist, as incredible as it seems.”

Zurita doused his head with water again and looked out the porthole to refresh himself.

“Whatever it is,” he continued, somewhat calmer, “this monstrous creature is endowed with human reason and can perform rational actions. It apparently feels equally at home in the water and on the surface. And it can speak Spanish – which means I can communicate with it. What if… What if I could catch the monster, tame it, and force it to dive for pearls! This one ‘toad,’ capable of living in water, could replace an entire crew of divers. And then, what profit! After all, each pearl diver has to be given a quarter of the catch. But this ‘toad’ wouldn’t cost anything. Why, this way I could make hundreds of thousands, millions of pesos in the shortest time!”

Zurita began to dream. Until now, he had hoped to get rich by searching for pearl oysters where no one else had harvested them. The Persian Gulf, the western coast of Ceylon, the Red Sea, Australian waters – all these pearl-rich areas were far away, and people had been searching for pearls there for a long time. Going to the Gulf of Mexico or California, to the islands of Tomas and Margarita? Zurita couldn’t sail to the coasts of Venezuela, where the best American pearls were harvested. For that, his schooner was too dilapidated, and he lacked divers – in short, he needed to expand his operations significantly. But Zurita didn’t have enough money. So he remained off the coast of Argentina. But now! Now he could become rich in a single year, if only he could catch “the sea devil.”

He would become the richest man in Argentina, perhaps even in America. Money would pave his way to power. Pedro Zurita’s name would be on everyone’s lips. But he had to be very careful. And first and foremost, keep it a secret.

Zurita went up on deck and, gathering the entire crew, down to the cook, said:

“Do you know what happened to those who spread rumors about the sea devil? The police arrested them, and they are in prison. I must warn you that the same will happen to each of you if you say even one word about seeing the sea devil. You’ll rot in prison. Do you understand? So, if your life is dear to you – not a word to anyone about the devil.”

“They wouldn’t believe them anyway: it all sounds too much like a fairy tale,” Zurita thought, and, calling Balthazar to his cabin, he confided his plan to him alone.

Balthazar listened carefully to his master and, after a silence, replied:

“Yes, this is good. The sea devil is worth hundreds of divers. It would be good to have the devil in one’s service. But how do we catch him?”

“With a net,” Zurita replied.

“He’ll cut through the net, just like he cut open the shark’s belly.”

“We can order a metal net.”

“And who will catch him? Just say ‘devil’ to our divers, and their knees buckle. They wouldn’t agree even for a bag of gold.”

“What about you, Balthazar?”

The Indian shrugged. “I’ve never hunted sea devils before. Stalking him probably won’t be easy, but killing him, if he’s made of flesh and bone, won’t be difficult. But you need a live devil.”

“Aren’t you afraid of him, Balthazar? What do you think of the sea devil?”

“What can I think of a jaguar that flies over the sea, or a shark that climbs trees? An unknown beast is scarier. But I love hunting scary beasts.”

“I’ll reward you handsomely.” Zurita shook Balthazar’s hand and continued to outline his plan:

“The fewer participants in this venture, the better. You talk to your Araucanians. They are brave and clever. Choose about five men, no more. If ours don’t agree, find others. The devil stays near the shores. First, we need to track down his lair. Then it will be easy for us to catch him in nets.”

Zurita and Balthazar quickly set to work. At Zurita’s order, a wire fish trap was made, resembling a large barrel with an open bottom. Inside the trap, Zurita stretched hemp nets so that “the devil” would get tangled in them like in a cobweb. The divers were dismissed. From the “Jellyfish”‘s crew, Balthazar managed to persuade only two Araucanian Indians to participate in the “devil” hunt. He recruited three more in Buenos Aires.

They decided to start tracking “the devil” in the bay where the “Jellyfish”‘s crew first saw him. So as not to arouse “the devil’s” suspicion, the schooner anchored a few kilometers from the small bay. Zurita and his companions occasionally fished, as if that were the sole purpose of their voyage. At the same time, three of them took turns, hiding behind rocks on the shore, keeping a sharp eye on what was happening in the bay’s waters.

The second week was drawing to a close, and “the devil” showed no sign of himself.

Balthazar struck up acquaintances with coastal residents, Indian farmers, selling them fish cheaply and, chatting with them about various things, subtly steered the conversation to “the sea devil.” From these conversations, the old Indian learned that they had chosen the right hunting ground: many Indians living near the bay had heard the sound of the horn and seen footprints on the sand. They insisted that “the devil’s” heel was human-like, but its toes were significantly elongated. Sometimes, on the sand, the Indians noticed an indentation from its back – it had been lying on the shore.

“The devil” did not harm the coastal residents, and they stopped paying attention to the tracks it left from time to time, reminding them of its presence. But no one had seen “the devil” itself.

For two weeks, the “Jellyfish” stood at anchor in the bay, ostensibly fishing. For two weeks, Zurita, Balthazar, and the hired Indians watched the ocean surface without a break, but “the sea devil” did not appear. Zurita was worried. He was impatient and stingy. Every day cost money, and this “devil” made them wait. Pedro began to doubt. If “the devil” was a supernatural being, no nets would catch him. And it was dangerous to deal with such a demon – Zurita was superstitious. Should he invite a priest with a cross and holy offerings aboard the “Jellyfish,” just in case? New expenses. But perhaps “the sea devil” was not a devil at all, but some prankster, a good swimmer, dressed up as a devil to scare people? A dolphin? But it, like any animal, could be tamed and trained. Should he abandon this whole endeavor?

Zurita offered a reward to whoever first spotted “the devil” and decided to wait a few more days.

To his joy, at the beginning of the third week, “the devil” finally began to appear.

After the day’s catch, Balthazar left a boat full of fish near the shore. Early in the morning, buyers were supposed to come for the fish.

Balthazar went to a farm to visit a familiar Indian, and when he returned to the shore, the boat was empty. Balthazar immediately decided that “the devil” had done it.

“Did he really eat so much fish?” Balthazar wondered.

That same night, one of the on-duty Indians heard the sound of a horn south of the bay. Two days later, early in the morning, a young Araucanian reported that he had finally managed to track “the devil.” He had arrived on a dolphin. This time, “the devil” was not riding it, but swimming next to the dolphin, holding onto a “harness” – a wide leather collar. In the bay, “the devil” removed the collar from the dolphin, patted the animal, and disappeared into the depths of the bay, at the base of a sheer rock. The dolphin swam to the surface and vanished.

Zurita, having listened to the Araucanian, thanked him, promised a reward, and said:

“The devil is unlikely to emerge from his hiding place this afternoon. Therefore, we need to inspect the bottom of the bay. Who will undertake this?”

But no one wanted to descend to the ocean floor, risking a face-to-face encounter with the unknown monster.

Balthazar stepped forward.

“Here I am!” he said curtly. Balthazar was true to his word. The “Jellyfish” was still at anchor. Everyone, except the watchmen, went ashore and headed to the sheer rock by the bay. Balthazar tied himself with a rope so he could be pulled out if he was injured, took a knife, clamped a stone between his legs, and descended to the bottom.

The Araucanians eagerly awaited his return, peering into the flickering spot in the bluish haze of the rock-shaded bay. Forty, fifty seconds passed, a minute – Balthazar did not return. Finally, he tugged the rope, and he was pulled to the surface. After catching his breath, Balthazar said:

“A narrow passage leads to an underwater cave. It’s as dark as a shark’s belly in there. The sea devil could only have hidden in this cave. Around it is a smooth wall.”

“Excellent!” Zurita exclaimed. “It’s dark there – even better! We’ll set our nets, and the fish will be caught.”

Soon after sunset, the Indians lowered the wire nets on strong ropes into the water at the cave’s entrance. The ends of the ropes were secured on the shore. Balthazar tied bells to the ropes, which would ring at the slightest touch of the net.

Zurita, Balthazar, and five Araucanians sat on the shore and waited in silence.

No one remained on the schooner.

Darkness quickly deepened. The moon rose, and its light reflected on the ocean’s surface. It was quiet. Everyone was gripped by extraordinary excitement. Perhaps now they would see the strange creature that had terrified fishermen and pearl seekers.

The night hours slowly passed. People began to doze.

Suddenly, the bells rang. The people jumped up, rushed to the ropes, and began to pull up the net. It was heavy. The ropes trembled. Someone was thrashing in the net.

Then the net appeared on the ocean’s surface, and within it, in the pale moonlight, thrashed the body of a half-human, half-animal. In the moonlight, huge eyes and silver scales gleamed. “The devil” made incredible efforts to free its hand, which was tangled in the net. It succeeded. It took out a knife, which hung from its hip on a thin strap, and began to cut the net.

“You won’t cut through that, you scamp!” Balthazar quietly said, engrossed in the hunt.

But to his surprise, the knife overcame the wire barrier. With nimble movements, “the devil” enlarged the hole, while the divers hurried to pull the net ashore.

“Harder! Heave-ho!” Balthazar was now shouting.

But at that very moment, when it seemed their prey was in their hands, “the devil” slipped through the cut hole, fell into the water, raising a cascade of sparkling splashes, and disappeared into the depths.

The divers dropped the net in despair.

“Good knife! Cuts wire!” Balthazar exclaimed with admiration. “Underwater blacksmiths are better than ours.”

Zurita, head bowed, stared at the water as if all his wealth had just sunk.

Then he lifted his head, tugged his bushy mustache, and stomped his foot.

“No, no, I won’t give up!” he cried. “You’ll die in your underwater cave before I retreat. I won’t spare any money; I’ll send for divers, I’ll cover the entire bay with nets and traps, and you won’t escape my grasp!”

He was brave, persistent, and stubborn. It was no coincidence that the blood of Spanish conquerors flowed in Pedro Zurita’s veins. And there was indeed something worth fighting for.

“The sea devil” turned out not to be a supernatural, omnipotent being. He was, evidently, made of flesh and bone, as Balthazar had said. This meant he could be caught, chained, and forced to retrieve wealth from the ocean floor for Zurita. Balthazar would get him, even if Neptune himself, the god of the sea, with his trident, came to the “sea devil’s” defense.

Doctor Salvator

Zurita was carrying out his threat. He built many wire fences at the bottom of the bay, stretched nets in all directions, and set traps. But his victims so far were only fish; “the sea devil” seemed to have vanished into thin air. He no longer appeared and gave no sign of his presence. In vain, the tamed dolphin appeared every day in the bay, diving and snorting, as if inviting his extraordinary friend for a swim. His friend did not show himself, and the dolphin, snorting angrily one last time, swam into the open sea.

The weather worsened. An easterly wind churned the ocean’s surface; the bay’s waters became cloudy with sand risen from the bottom. Foaming wave crests hid the seabed. No one could see what was happening underwater.

Zurita could stand on the shore for hours, looking at the rows of waves. Huge, they came one after another, crashing down in noisy waterfalls, while the lower layers of water hissed further over the wet sand, turning pebbles and shells, rolling up to Zurita’s feet.

“No, this won’t do,” Zurita said. “We need to come up with something else. The devil lives at the bottom of the sea and doesn’t want to leave his hiding place. So, to catch him, we need to go to him – descend to the bottom. That’s clear!”

And, turning to Balthazar, who was crafting a new, complex trap, Zurita said:

“Go to Buenos Aires immediately and bring back two diving suits with oxygen tanks. A regular diving suit with a hose for air supply won’t do. The devil could cut the hose. Besides, we might have to make a small underwater journey. And don’t forget to bring electric torches.”

“You wish to visit the devil?” Balthazar asked.

“With you, of course, old man.” Balthazar nodded and set off. He brought not only diving suits and torches but also a pair of long, intricately curved bronze knives.

“They don’t make these anymore,” he said. “These are ancient Araucanian knives, which my great-grandfathers once used to slit the bellies of white men – your great-grandfathers, no offense meant.”

Zurita didn’t like this historical note, but he approved of the knives.

“You are very thoughtful, Balthazar.”

The next day, at dawn, despite the heavy waves, Zurita and Balthazar put on their diving suits and descended to the seabed. With some difficulty, they untangled the nets at the entrance to the underwater cave and squeezed into the narrow passage. Complete darkness surrounded them. Standing up and drawing their knives, the divers turned on their torches. Frightened by the light, small fish darted away, then swam back to the torch, fluttering in its bluish beam like a swarm of insects.

Zurita waved them away with his hand; their shimmering scales blinded him. It was a fairly large cave, at least four meters high and five to six meters wide. The divers examined the corners. The cave was empty and uninhabited. Only schools of small fish apparently sheltered there from the rough sea and predators.

Stepping carefully, Zurita and Balthazar moved forward. The cave gradually narrowed. Suddenly, Zurita stopped in amazement. The torchlight illuminated a thick iron grating blocking the path.

Zurita couldn’t believe his eyes. He grabbed the iron bars and began to pull at them, trying to open the iron barrier. But the grating wouldn’t budge. Lighting it with his torch, Zurita saw that the grating was firmly set into the hewn walls of the cave and had hinges and an internal lock.

This was a new mystery.

“The sea devil” must be not only intelligent but also an exceptionally gifted creature.

He managed to tame a dolphin, he knows how to process metals. Finally, he could have created strong iron barriers at the bottom of the sea to guard his dwelling. But that’s incredible! He couldn’t have forged iron underwater. That means he doesn’t live in the water, or at least he comes out of the water onto land for long periods.

Zurita’s temples throbbed, as if there wasn’t enough oxygen in his diving helmet, even though he had only been in the water for a few minutes.

Zurita signaled to Balthazar, and they emerged from the underwater cave – there was nothing more for them to do there – and ascended to the surface.

The Araucanians, who had been impatiently waiting for them, were very relieved to see the divers unharmed.

Taking off his helmet and catching his breath, Zurita asked:

“What do you say to this, Balthazar?” The Araucanian spread his hands.

“I say we’ll have to wait here for a long time. The devil probably feeds on fish, and there’s enough fish there. We won’t starve him out of the cave. We’ll just have to blast the grating with dynamite.” “And don’t you think, Balthazar, that the cave might have two exits: one from the bay and another from the surface?” Balthazar hadn’t thought of that.

“Then we need to think about it. How did we not think to examine the surroundings before?” Zurita said.

Now they began to examine the shore.

On the shore, Zurita stumbled upon a high white stone wall, encircling a huge plot of land – no less than ten hectares. Zurita walked around the wall. In the entire wall, he found only one gate, made of thick sheets of iron. In the gate was a small iron door with a spinner mechanism covered from the inside.

“A real prison or fortress,” Zurita thought. “Strange! Farmers don’t build such thick and high walls. There’s not a single opening or crack in the wall to peek through.”

All around was a deserted, wild landscape: bare gray rocks, sparsely covered with thorny bushes and cacti. Below lay the bay.

For several days, Zurita roamed along the wall, observing the iron gate for long stretches. But the gate remained closed; no one entered or left; not a sound reached him from beyond the wall.

Returning to the “Jellyfish”‘s deck in the evening, Zurita called Balthazar and asked:

“Do you know who lives in the fortress above the bay?”

“Yes, I’ve already asked the Indians working on the farms about it. Salvator lives there.”

“Who is he, this Salvator?”

“A god,” Balthazar replied.

Zurita raised his thick black eyebrows in astonishment.

“Are you joking, Balthazar?” The Indian smiled almost imperceptibly.

“I’m repeating what I’ve heard. Many Indians call Salvator a deity, a savior.”

“What does he save them from?”

“From death. They say he is omnipotent. Salvator can work miracles. He holds life and death in his fingers. He gives new legs, living legs, to the lame, sharp, eagle-like eyes to the blind, and even resurrects the dead.”

“Damn it!” Zurita grumbled, stroking his bushy mustache upwards with his fingers. “A sea devil in the bay, a god above the bay. Don’t you think, Balthazar, that the devil and the god might be helping each other?”

“I think we should get out of here as soon as possible, before our brains curdle like sour milk from all these miracles.”

“Have you seen anyone yourself whom Salvator has healed?”

“Yes, I have. They showed me a man with a broken leg. After visiting Salvator, that man runs like a mustang. I also saw an Indian resurrected by Salvator. The whole village says that this Indian, when he was carried to Salvator, was a cold corpse – his skull split open, brains exposed. But he came back from Salvator alive and cheerful. He even married after death. Took a good girl. And I’ve also seen Indian children…”

“So, Salvator receives outsiders?”

“Only Indians. And they come to him from everywhere: from Tierra del Fuego and the Amazon, from the Atacama Desert and Asunción.”

Having received this information from Balthazar, Zurita decided to go to Buenos Aires.

There he learned that Salvator healed Indians and was renowned among them as a miracle worker. Inquiring with doctors, Zurita found out that Salvator was a talented and even brilliant surgeon, but a man with great eccentricities, like many outstanding people. Salvator’s name was widely known in scientific circles of the Old and New Worlds. In America, he gained fame for his daring surgical operations. When patients’ conditions were deemed hopeless and doctors refused to operate, Salvator was called. He never refused. His courage and resourcefulness were boundless. During the imperialist war, he was on the French front, where he dealt almost exclusively with skull operations. Many thousands of people owed their salvation to him. After the peace treaty, he returned to his homeland, Argentina. Medical practice and successful land speculations brought Salvator an enormous fortune. He bought a large plot of land near Buenos Aires, surrounded it with a huge wall – one of his peculiarities – and, settling there, ceased all practice. He engaged only in scientific work in his laboratory. Now he treated and received Indians, who called him a god descended to earth.

Zurita managed to learn one more detail concerning Salvator’s life. Where Salvator’s extensive estate now stood, before the war there was a small house with a garden, also enclosed by a stone wall. All the time Salvator was at the front, this house was guarded by a Black man and several huge dogs. Not a single person was allowed into the yard by these incorruptible guards.

Recently, Salvator had surrounded himself with even greater mystery. He didn’t even receive former university colleagues.

Learning all this, Zurita decided:

“If Salvator is a doctor, he has no right to refuse a patient. Why shouldn’t I fall ill? I’ll get to Salvator under the guise of being sick, and then we’ll see.”

Zurita went to the iron gate guarding Salvator’s estate and began to knock. He knocked long and hard, but no one opened. Enraged, Zurita picked up a large stone and began to pound it against the gate, making a noise that could wake the dead.

Far behind the wall, dogs barked, and finally, the peep-hole in the door opened slightly.

“What do you want?” someone asked in broken Spanish.

“I’m sick, open up quickly,” Zurita replied.

“Sick people don’t knock like that,” the same voice calmly retorted, and an eye appeared in the peep-hole. “The doctor isn’t seeing anyone.”

“He doesn’t dare refuse help to a sick person,” Zurita flared.

The peep-hole closed, and the footsteps receded. Only the dogs continued to bark desperately.

Zurita, having exhausted his entire supply of curses, returned to the schooner. Complain about Salvator in Buenos Aires? But that would lead nowhere. Zurita trembled with rage. His bushy black mustache was in serious danger, as in his agitation he kept tugging at it, and it drooped downwards like a barometer needle indicating low pressure.

Gradually, he calmed down and began to ponder his next move.

As he thought, his tan fingers more and more frequently brushed his disheveled mustache upwards. The barometer was rising.

Finally, he went up on deck and, unexpectedly for everyone, gave the order to weigh anchor.

The “Jellyfish” set course for Buenos Aires.

“Good,” Balthazar said. “What a waste of time! To hell with this devil and god alike!”

Ailing Granddaughter

The sun beat down mercilessly.

Along a dusty road, winding through fields heavy with wheat, corn, and oats, walked an old, emaciated Indian man. His clothes were torn. In his arms, he carried a sick child, covered from the sun’s rays by a worn blanket. The child’s eyes were half-closed. A large swelling was visible on its neck. From time to time, when the old man stumbled, the child would groan hoarsely and partly open its eyelids. The old man would stop, carefully blowing on the child’s face to refresh it.

“Just to get there alive!” the old man whispered, quickening his steps.

Reaching the iron gate, the Indian shifted the child to his left arm and struck the iron door four times with his right hand. The small flap in the wicket gate opened slightly, an eye flickered in the opening, bolts creaked, and the wicket gate opened.

The Indian timidly stepped over the threshold. Before him stood an old Black man dressed in a white robe, with completely white curly hair.

“To the doctor, the child is sick,” the Indian said.

The Black man nodded silently, locked the door, and motioned for him to follow.

The Indian looked around. They were in a small courtyard paved with wide stone slabs. This courtyard was enclosed on one side by a high outer wall, and on the other by a lower wall separating the courtyard from the inner part of the estate. No grass, no green bush — a real prison yard. In the corner of the courtyard, by the gate of the second wall, stood a white house with large, wide windows. Near the house, Indians — men and women — sat on the ground. Many were with children.

Almost all the children looked perfectly healthy. Some played “odds and evens” with seashells, others wrestled silently — the old Black man with white hair strictly ensured the children didn’t make noise.

The old Indian meekly sat on the ground in the shade of the house and began to blow on the child’s motionless, bluish face. Next to the Indian sat an old Indian woman with a swollen leg. She looked at the child lying on the Indian’s lap and asked:

“Daughter?”

“Granddaughter,” the Indian replied. Shaking her head, the old woman said:

“A swamp spirit has entered your granddaughter. But he is stronger than evil spirits. He will drive out the swamp spirit, and your granddaughter will be well.”

The Indian nodded affirmatively.

The Black man in the white robe walked around the sick, looked at the Indian’s child, and pointed to the house door.

The Indian entered a large room with a stone slab floor. In the middle of the room stood a narrow, long table covered with a white sheet. A second door, with frosted glass, opened, and Doctor Salvator entered the room, wearing a white robe, tall, broad-shouldered, dark-skinned. Except for his black eyebrows and eyelashes, Salvator had no hair on his head. Apparently, he shaved his head constantly, as the skin on his head was as tanned as on his face. A rather large, aquiline nose, a somewhat protruding, sharp chin, and tightly compressed lips gave his face a cruel, even predatory expression. His brown eyes gazed coldly. Under this gaze, the Indian felt uneasy.

The Indian bowed low and extended the child. Salvator, with a quick, confident yet gentle movement, took the sick girl from the Indian’s hands, unwrapped the rags the child was bundled in, and threw them into the corner of the room, skillfully landing them in a box standing there. The Indian hobbled towards the box, wishing to retrieve the rags, but Salvator strictly stopped him:

“Leave them, don’t touch!”

Then he placed the girl on the table and leaned over her. He stood in profile to the Indian. And suddenly, it seemed to the Indian that it was not a doctor, but a condor leaning over a small bird. Salvator began to palpate the swelling on the child’s throat with his fingers. These fingers also struck the Indian. They were long, extraordinarily mobile fingers. It seemed they could bend at the joints not only downwards, but also sideways and even upwards. The far-from-timid Indian tried not to succumb to the fear that this incomprehensible man instilled in him.

“Excellent. Magnificent,” Salvator said, as if admiring the swelling and feeling it with his fingers.

Having finished the examination, Salvator turned his face to the Indian and said:

“It’s a new moon now. Come back in a month, at the next new moon, and you will have your girl healthy.”

He carried the child through the glass door, where the bathroom, operating room, and patient wards were located. And the Black man was already ushering a new patient into the reception room — an old woman with a sore leg.

The Indian bowed low to the glass door that closed behind Salvator and left.

Exactly twenty-eight days later, the same glass door opened.

In the doorway stood a girl in a new dress, healthy and rosy-cheeked. She looked timidly at her grandfather. The Indian rushed to her, grabbed her hands, kissed her all over, and examined her throat. There was no trace of the swelling. Only a small, barely visible reddish scar remained to remind him of the operation.

The girl pushed her grandfather away with her hands and even cried out when he, having kissed her, pricked her with his unshaven chin. He had to put her down on the floor. Salvator entered right after the girl. Now the doctor even smiled and, patting the girl’s head, said:

“Well, take your girl. You brought her just in time. A few more hours, and even I wouldn’t have been able to save her life.”

The old Indian’s face was covered with wrinkles, his lips twitched, and tears streamed from his eyes. He lifted the girl again, pressed her to his chest, fell to his knees before Salvator, and said in a voice choked with tears:

“You saved my granddaughter’s life. What can a poor Indian offer you as a reward, besides his life?”

“What do I need your life for?” Salvator asked, surprised.

“I am old, but still strong,” the Indian continued, without rising from the floor. “I will take my granddaughter to her mother — my daughter — and return to you. I want to give you the rest of my life for the good you have done for me. I will serve you like a dog. Please, do not refuse me this favor.”

Salvator thought for a moment.

He was very reluctant and cautious about taking on new servants. Although there would be work. A lot of work, in fact — Jim wasn’t managing in the garden. This Indian seemed like a suitable person, though the doctor would have preferred a Black man.

“You are giving me your life and asking, as a favor, for me to accept your gift. Very well. Have it your way. When can you come?”

“Before the first quarter moon ends, I will be here,” the Indian said, kissing the hem of Salvator’s robe.

“What is your name?”

“Mine?… Kristo — Christopher.”

“Go, Kristo. I will wait for you.”

“Let’s go, granddaughter!” Kristo said to the girl and picked her up again.

The girl cried. Kristo hurried away.

The Marvelous Garden

When Kristo arrived a week later, Doctor Salvator looked intently into his eyes and said:

“Listen carefully, Kristo. I’m taking you into my service. You will receive room and board and a good salary…” Kristo waved his hands:

“I need nothing, only to serve you.”

“Be silent and listen,” Salvator continued. “You will have everything. But I will demand one thing: you must be silent about everything you see here.”

“I would sooner cut out my tongue and throw it to the dogs than say a single word.”

“See to it that such misfortune does not befall you,” Salvator warned. And, summoning the Black man in the white robe, the doctor ordered:

“Lead him to the garden and hand him over to Jim.”

The Black man bowed silently, led the Indian out of the white house, through the courtyard Kristo already knew, and knocked on the iron gate of the second wall.

From behind the wall, the barking of dogs was heard. The gate creaked and slowly opened.

The Black man pushed Kristo through the gate into the garden, gutturally shouted something to another Black man standing behind the gate, and left.

Kristo, startled, pressed himself against the wall: with barks resembling roars, unknown, reddish-yellow beasts with dark spots ran towards him. If Kristo had met them in the pampas, he would have immediately recognized them as jaguars. But the beasts running towards him barked like dogs. At that moment, Kristo didn’t care what animals were attacking him. He rushed to a nearby tree and began to climb its branches with unexpected speed. The Black man hissed at the dogs like an angry cobra. This immediately calmed the dogs. They stopped barking, lay on the ground, and rested their heads on their outstretched paws, glancing sidelong at the Black man.

The Black man hissed again, this time addressing Kristo, who was sitting in the tree, and waved his hands, inviting the Indian to come down.

“Why are you hissing like a snake?” Kristo said, not leaving his refuge. “Swallowed your tongue?” The Black man only grunted angrily.

“He must be mute,” Kristo thought, remembering Salvator’s warning. Did Salvator cut out the tongues of servants who revealed his secrets? Perhaps this Black man also had his tongue cut out… And Kristo suddenly felt so terrified that he nearly fell from the tree. He wanted to escape from there at all costs and as quickly as possible. He mentally calculated the distance from the tree he was in to the wall. No, he couldn’t jump… But the Black man approached the tree and, grabbing the Indian by the leg, impatiently pulled him down. Kristo had to obey. He jumped from the tree, smiled as politely as he could, extended his hand, and asked in a friendly tone:

“Jim?”

The Black man nodded.

Kristo firmly shook the Black man’s hand. “If I’ve ended up in hell, I might as well get along with the devils,” he thought, and continued aloud:

“Are you mute?” The Black man remained silent.

“No tongue?”

The Black man was still silent.

“How can I look into his mouth?” Kristo wondered. But Jim apparently had no intention of engaging even in mimed conversation. He took Kristo’s hand, led him to the reddish-brown beasts, and hissed something at them. The beasts rose, approached Kristo, sniffed him, and calmly walked away. Kristo felt a little relief.

Waving his hand, Jim led Kristo to inspect the garden.

After the gloomy, stone-paved courtyard, the garden was astonishing in its abundance of greenery and flowers. The garden stretched eastward, gradually sloping down towards the seashore. Paths, strewn with reddish crushed shells, branched in different directions. Along the paths grew whimsical cacti and bluish-green succulent agaves, with plumes of numerous yellowish-green flowers. Entire groves of peach and olive trees shaded dense grass with colorful, bright flowers. Amidst the green grass gleamed ponds, lined with white stones. Tall fountains refreshed the air.

The garden was filled with a cacophony of cries, singing, and chirping of birds, roars, squeaks, and squeals of animals. Never before had Kristo seen such unusual animals. Unseen beasts lived in this garden.

Here, a six-legged lizard, gleaming with copper-green scales, scurried across the path. From a tree hung a two-headed snake. Kristo, startled, leaped sideways from the two-headed reptile, which hissed at him with two red mouths. The Black man answered it with a louder hiss, and the snake, waving its heads in the air, fell from the tree and disappeared into the dense thickets of reeds. Another long snake crawled off the path, clinging with two paws. Behind a wire mesh, a piglet grunted. It stared at Kristo with a single large eye set in the middle of its forehead.

Two white rats, fused at the sides, ran along the pink path like a two-headed, eight-legged monster. Sometimes this two-in-one creature began to fight with itself: the right rat pulled to the right, the left to the left, and both squeaked discontentedly. But the right one always won. Next to the path grazed conjoined “Siamese twins” — two fine-wooled sheep. They didn’t quarrel like the rats. Between them, apparently, a complete unity of will and desires had long been established. One deformity particularly struck Kristo: a large, completely naked pink dog. And on its back, as if emerging from the dog’s body, was a small monkey — its chest, arms, head. The dog approached Kristo and wagged its tail. The monkey twisted its head, flailed its arms, patted the dog’s back, with which it formed a single entity, and screamed, looking at Kristo. The Indian reached into his pocket, took out a piece of sugar, and offered it to the monkey. But someone quickly moved Kristo’s hand aside. A hiss was heard behind him. Kristo looked around — Jim. The old Black man explained to Kristo with gestures and facial expressions that the monkey could not be fed. And immediately, a sparrow with the head of a small parrot snatched the piece of sugar from Kristo’s fingers in flight and disappeared behind a bush. In the distance on the lawn, a horse with a cow’s head mooed.

Two llamas galloped across the clearing, wagging horse tails. From the grass, from the thickets of bushes, from the branches of trees, unusual reptiles, beasts, and birds looked at Kristo: dogs with cat heads, geese with rooster heads, horned wild boars, rheas with eagle beaks, rams with puma bodies…

Kristo felt as if he were delirious. He rubbed his eyes, moistened his head with cold fountain water, but nothing helped. In the ponds, he saw snakes with fish heads and gills, fish with frog legs, huge toads with bodies as long as lizards…

And Kristo again wanted to escape from there.

But then Jim led Kristo to a wide, sand-strewn platform. In the middle of the platform, surrounded by palm trees, stood a villa of white marble, built in Moorish style. Arches and columns were visible through the palm trunks. — Copper fountains in the form of dolphins cast cascades of water into transparent ponds with golden fish playing in them. The largest fountain in front of the main entrance depicted a young man sitting on a dolphin like the mythical Triton, with a twisted horn at his mouth.

Behind the villa were several residential buildings and outbuildings, and further on were dense thickets of thorny cacti, reaching to the white wall.

“Another wall!” Kristo thought.

Jim led the Indian into a small, cool room. With gestures, he explained that this room was for him, and left, leaving Kristo alone.

The Third Wall

Little by little, Kristo grew accustomed to the extraordinary world that surrounded him. All the animals, birds, and reptiles that filled the garden were well-tamed. Kristo even formed friendships with some of them. The jaguar-skinned dogs, which had so frightened him on his first day, now followed him closely, licked his hands, and nuzzled him. The llamas ate bread from his hands. Parrots flew down to perch on his shoulder.

The garden and its animals were cared for by twelve Black men, as silent or mute as Jim. Kristo had never heard them speak, not even to each other. Each silently went about his work. Jim was something of a manager. He oversaw the Black men and assigned their duties. And Kristo, to his own surprise, was appointed Jim’s assistant. Kristo didn’t have much work, and he was well-fed. He couldn’t complain about his life. One thing bothered him — the ominous silence of the Black men. He was convinced that Salvator had cut out all their tongues. And when Salvator occasionally summoned Kristo, the Indian always thought: “Time to cut my tongue.” But soon Kristo became less afraid for his tongue.

One day Kristo saw Jim sleeping in the shade of the olive trees. The Black man was lying on his back, mouth open. Kristo took advantage of this, cautiously peered into the sleeping man’s mouth, and confirmed that the old Black man’s tongue was in place. Then the Indian felt somewhat relieved.

Salvator strictly scheduled his day. From seven to nine in the morning, the doctor received sick Indians; from nine to eleven, he operated; then he retreated to his villa and worked in his laboratory. He operated on animals and then studied them extensively. When his observations concluded, Salvator sent these animals to the garden. Kristo, sometimes tidying the house, would sneak into the laboratory. Everything he saw there astonished him. Various organs pulsed in glass jars filled with some solutions. Severed hands and legs continued to live. And when these living parts, detached from the body, began to ache, Salvator treated them, restoring their fading life.

All of this filled Kristo with dread. He preferred to be among the living deformities in the garden.

Despite the trust Salvator placed in the Indian, Kristo dared not venture beyond the third wall. And this greatly interested him. One midday, when everyone was resting, Kristo ran to the high wall. From beyond the wall, he heard children’s voices — he distinguished Indian words. But sometimes, even finer, squealing voices joined the children’s, as if arguing with the children and speaking in some incomprehensible dialect.

One day, meeting Kristo in the garden, Salvator approached him and, as was his custom, looking directly into his eyes, said:

“You’ve been working for me for a month now, Kristo, and I am pleased with you. One of my servants in the lower garden has fallen ill. You will replace him. You will see many new things there. But remember our agreement: keep your tongue firmly in your teeth, if you don’t want to lose it.”

“I’ve almost forgotten how to speak among your mute servants,” Kristo replied.

“All the better. Silence is golden. If you keep silent, you will receive many gold pesos. I hope to have my sick servant back on his feet in two weeks. By the way, do you know the Andes well?”

“I was born in the mountains.”

“Excellent. I will need to replenish my menagerie with new animals and birds. I will take you with me. Now go. Jim will lead you to the lower garden.”

Kristo had grown accustomed to many things. But what he saw in the lower garden surpassed his expectations.

In a large, sunlit meadow, naked children and monkeys frolicked. These were children from different Indian tribes. Among them were very young ones — no more than three years old; the oldest were about twelve. These children were Salvator’s patients. Many of them had undergone serious operations and owed their lives to Salvator. The convalescing children played and ran in the garden, and then, when their strength returned, their parents took them home.

Besides the children, monkeys lived here. Tailless monkeys. Monkeys with no trace of fur on their bodies.

Most surprisingly, all the monkeys, some better than others, could speak. They argued with the children, cursed, and squealed in high-pitched voices. Yet, the monkeys coexisted peacefully with the children and quarreled with them no more than the children among themselves.

Kristo sometimes couldn’t decide whether they were real monkeys or humans.

When Kristo became acquainted with the garden, he noticed that this garden was smaller than the upper one and sloped even more steeply towards the bay, ending at a sheer, wall-like rock.

The sea was probably not far beyond this wall. The roar of the sea surf drifted from behind the wall.

After exploring this rock a few days later, Kristo confirmed that it was artificial. In dense thickets of wisteria, Kristo discovered a gray iron door, painted to match the rocks, perfectly blending with them.

Kristo listened. No sound, except the surf, reached him from beyond the rock. Where did this narrow door lead? To the seashore?

Suddenly, an excited child’s cry was heard. The children were looking at the sky. Kristo looked up and saw a small red child’s balloon slowly flying across the garden. The wind carried the balloon towards the sea.

A common child’s balloon flying over the garden greatly agitated Kristo. He began to worry. And as soon as the recovered servant returned, Kristo went to Salvator and said:

“Doctor! We are going to the Andes soon, perhaps for a long time. Allow me to see my daughter and granddaughter.”

Salvator disliked his servants leaving the estate and preferred to have single ones. Kristo waited silently, looking into Salvator’s eyes.

Salvator, looking coldly at Kristo, reminded him:

“Remember our agreement. Guard your tongue! Return no later than three days. Wait!”

Salvator withdrew to another room and brought out a chamois pouch from which golden pesos jingled.

“Here for your granddaughter. And for your silence.”

The Attack

“If he doesn’t come today, I’ll refuse your help, Balthazar, and invite more skillful and reliable men,” Zurita said, impatiently twitching his bushy mustache.

Zurita was now dressed in a white city suit and a Panama hat. He met Balthazar on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, where the cultivated fields ended and the pampas began.

Balthazar, in a white blouse and blue striped trousers, sat by the road and remained silent, nervously plucking at the sun-scorched grass.

He himself was beginning to regret sending his brother Kristo to Salvator as a spy.

Kristo was ten years older than Balthazar. Despite his age, Kristo remained a strong and agile man. He was cunning as a pampas cat. Yet, he was an unreliable person. He had tried farming — found it boring. Then he ran a tavern in the port, but, becoming addicted to wine, he quickly went bankrupt.

In recent years, Kristo had been involved in the darkest affairs, employing his extraordinary cunning and at times treachery. Such a man was a suitable spy, but he could not be trusted. If it benefited him, he could betray even his own brother. Balthazar knew this and was therefore no less worried than Zurita.

“Are you sure Kristo saw the balloon you released?”

Balthazar vaguely shrugged, wishing he could abandon this whole scheme, go home, quench his thirst with cold water and wine, and turn in early.

The last rays of the setting sun illuminated plumes of dust rising from behind the hill. At the same time, a sharp, prolonged whistle cut through the air.

Balthazar perked up.

“It’s him!”

“Finally!”

Kristo approached them with a brisk stride, no longer resembling the emaciated old Indian. With another jaunty whistle, Kristo reached them and greeted Balthazar and Zurita.

“Well, have you met the sea devil?” Zurita asked him.

“Not yet, but he’s there. Salvator keeps the devil behind four walls. The main thing is done: I serve Salvator, and he trusts me. The sick granddaughter worked out perfectly for me,” Kristo chuckled, narrowing his cunning eyes. “She almost ruined it when she recovered. I hugged and kissed her, as a loving grandfather should, and that silly girl started kicking and nearly cried.” Kristo laughed again.

“Where did you get your granddaughter?” Zurita inquired.

“Money’s hard to find, girls are easy,” Kristo replied. “The child’s mother is happy. I got five paper pesos from her, and she got a healthy girl.”

Kristo discreetly omitted the fact that he’d received a hefty pouch of gold pesos from Salvator. Of course, he had no intention of giving that money to the girl’s mother.

“There are wonders at Salvator’s. A real menagerie.” Kristo then proceeded to recount everything he had seen.

“This is all very interesting,” Zurita said, lighting a cigar, “but you haven’t seen the main thing: the devil. What do you plan to do next, Kristo?”

“Next? Take a short trip to the Andes.” Kristo then explained that Salvator was preparing for an animal hunt.

“Excellent!” Zurita exclaimed. “Salvator’s estate is far from other settlements. In his absence, we’ll attack his property and kidnap the sea devil.”

Kristo shook his head negatively.

“Jaguars will rip your head off, and you won’t be able to find the devil. You won’t find him even with your head, if I couldn’t.”

“Then here’s what,” Zurita said, after a moment’s thought, “we’ll set an ambush when Salvator goes hunting; we’ll capture him and demand a ransom — the sea devil.”

With a deft movement, Kristo plucked the cigar protruding from Zurita’s side pocket.

“Thank you. An ambush is better. But Salvator will deceive us: he’ll promise a ransom and won’t deliver. These Spaniards…” Kristo coughed.

“What do you propose then?” Zurita asked, now with irritation.

“Patience, Zurita. Salvator trusts me, but only up to the fourth wall. The doctor needs to trust me as much as he trusts himself, and then he’ll show me the devil.”

“Well?”

“Well, this is it. Bandits will attack Salvator,” — and Kristo poked Zurita’s chest with his finger — “and I,” — he struck his own chest — “an honest Araucanian, will save his life. Then there will be no secrets for Kristo in Salvator’s house. (“And my wallet will be filled with gold pesos,” he finished to himself.) “Well, that’s not bad.”

They then agreed on the road Kristo would take Salvator.

“The day before we leave, I’ll throw a red stone over the fence. Be ready.”

Despite the meticulous planning of the attack, one unforeseen circumstance almost ruined everything.

Zurita, Balthazar, and ten thugs recruited from the port, dressed as gauchos and well-armed, waited on horseback for their victim far from any habitation.

It was a dark night. The riders listened, expecting to hear the thud of horse hooves. But Kristo didn’t know that Salvator no longer went hunting in the same way he had years ago.

The bandits suddenly heard the rapidly approaching roar of an engine. From behind a hill, dazzling headlights flashed. A huge black car sped past the riders before they could even grasp what had happened.

Zurita cursed desperately. Balthazar found it amusing.

“Don’t be upset, Pedro,” the Indian said. “It’s hot during the day; they drive at night — Salvator has two suns on his car. They’ll rest during the day. We can catch up with them at a stop.” And, spurring his horse, Balthazar galloped after the car.

The others followed him.

After riding for about two hours, the horsemen unexpectedly spotted a campfire in the distance.

“That’s them. Something must have happened to them. Wait, I’ll crawl over and find out. Wait for me.”

And, dismounting, Balthazar crawled like a snake. An hour later, he returned.

“The car’s broken down. They’re fixing it. Kristo is on watch. We need to hurry.”

Everything else happened very quickly. The bandits attacked. Before Salvator could react, he, Kristo, and three of the Black men had their hands and feet tied.

One of the hired bandits, the gang leader — Zurita preferred to stay in the shadows — demanded a sizable ransom from Salvator.

“I will pay, release me,” Salvator replied.

“That’s for you. But you must pay the same amount for your three companions!” the bandit quickly added.

“I can’t give such a sum at once,” Salvator responded after thinking.

“Then death to him!” the bandits shouted.

“If you don’t agree to our terms, we will kill you at dawn,” the bandit stated.

Salvator shrugged and replied, “I don’t have that amount on hand.”

Salvator’s calmness surprised even the bandit.

Leaving the bound captives behind the car, the bandits began to search and found supplies of alcohol meant for collections. They drank the alcohol and, drunk, collapsed to the ground.

Shortly before dawn, someone cautiously crawled up to Salvator.

“It’s me,” Kristo whispered quietly. “I managed to untie the straps. I crept up to the bandit with the rifle and killed him. The others are drunk. The chauffeur fixed the car. We need to hurry.”

Everyone quickly got into the car, the Black chauffeur started the engine, and the car surged forward, speeding down the road.

Behind them, shouts and disorganized gunfire were heard.

Salvator firmly shook Kristo’s hand.

Only after Salvator’s departure did Zurita learn from his bandits that Salvator had agreed to pay the ransom. “Wouldn’t it have been simpler,” Zurita mused, “to get the ransom than to try to kidnap the sea devil, who knows what he even is?” But the opportunity was missed; all that remained was to await news from Kristo.

The Amphibious Man

Kristo hoped that Salvator would approach him and say, “Kristo, you saved my life. Now there are no secrets for you in my domain. Come, I’ll show you the sea devil.”