FOREWORD

“ORDER IN THE TANK FORCES…”

And in peaceful years we sacredly maintain

Order in the tank forces.

(From a song)

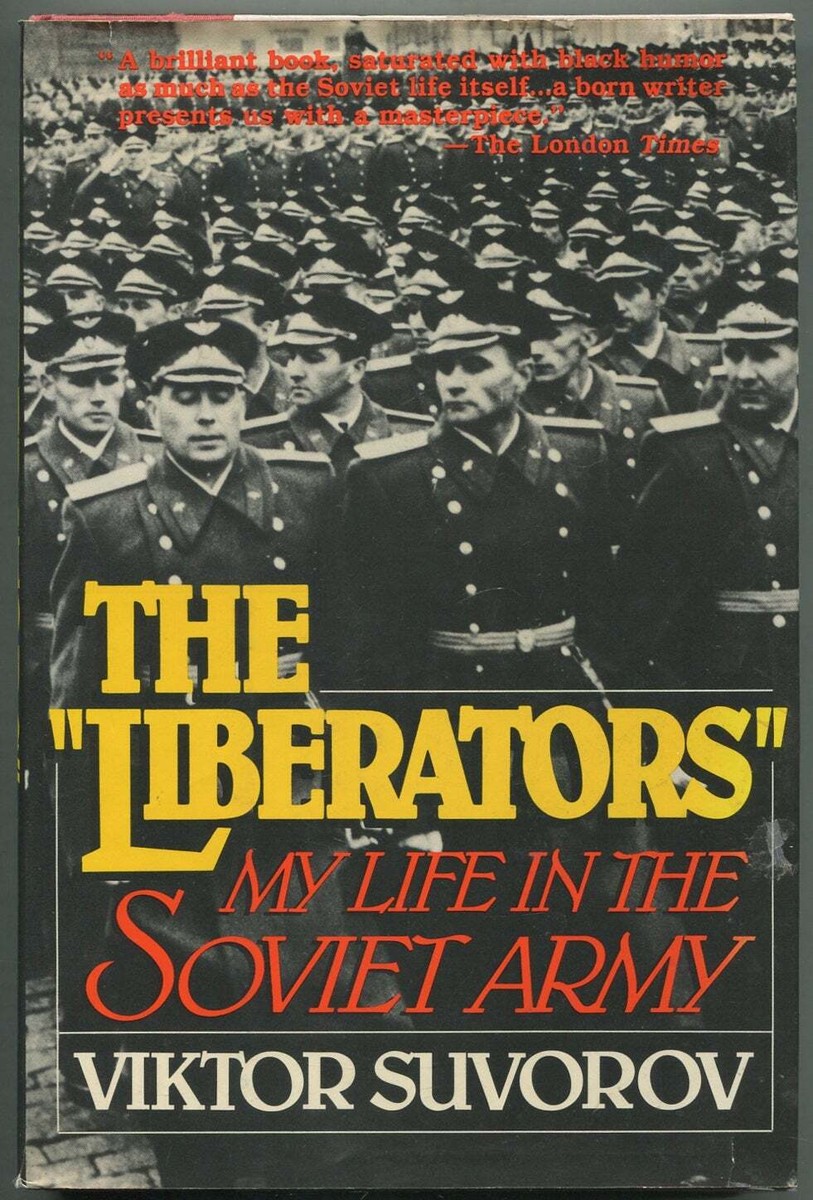

Viktor Suvorov’s book reaches the Russian reader late: it appeared in English in 1981, in French in 1982, and was translated into many other languages. Everywhere it sparked great interest. And how could it be otherwise: the author, a Soviet officer, describes the largest, most formidable army in the world “from the inside.” Moreover, the book, titled The Liberators’ Tales, because it recounts the “liberation” of Czechoslovakia in 1968, reached the reader at the very moment the Soviet Army began the “liberation” of Afghanistan.

The author is a collective farm driver, then a cadet at a tank school, an officer, then—the Military Diplomatic Academy, service in the GRU, including as an “intelligence officer” in Western Europe…

The French philosopher Pascal remarked that one should only believe witnesses who are ready to have their throats slit. The death sentence passed in absentia on Viktor Suvorov confirms the authenticity of his testimony. The Liberators’ Tales possesses yet another important virtue: the author is a fascinating storyteller, a ruthless portraitist, who readily resorts to the weapon of satire.

There is a parable. A man crucified on a cross, pierced by pikes, arrows, is asked: does it hurt? The man answers: only when I laugh. Laughter doesn’t allow one to forget the pain, doesn’t allow one to reconcile with a situation that seems hopeless.

Viktor Suvorov compiled his book from short stories about the life of a cadet, then a tank officer: the guardhouse, drill practice, exercises, combat vehicles, subordinates, and superiors, and then—the “combat campaign” into fraternal Czechoslovakia. The stories—like pebbles in a mosaic—form a picture. Before the reader is the army of the Land of Soviets, the country of mature socialism. The very army that 60 years ago sang: “But from the taiga to the British seas, the Red Army is the strongest of all,” and today sings: “We walked… we walked halfway around the world with you, if necessary—we will repeat it!”

The army—there is no need to prove the axiom—is a mirror reflecting the country. As the country is, so is the army. Or: as the army is, so is the country. The Liberators’ Tales is, secondarily, a book about army life. First and foremost, it is a magnificent description of Soviet life, of the Soviet system. Viktor Suvorov asks—on the first page—to retain the dedication to Brezhnev, in whose “glorious times” the book was written. But everything described in The Liberators’ Tales remains relevant today, except for the disappearance of some high officials and their replacement by twins.

In the army (just as in a camp), the Soviet person does not feel like they are in a foreign place: everything is like home. The senseless drill on the barracks yard is only seen as an intensified form of educational work. The question of a cadet sitting in the guardhouse: “Will there be a guardhouse under Communism?”—receives a politically correct answer that causes no doubt in anyone: “There will always be a guardhouse!” The constant hunger of the soldiers, who, as V. Suvorov writes, “are fed worse than any other soldiers in the world,” seems natural. Food difficulties have not ceased to bother the Soviet person for 70 years. It is understandable, therefore, that when Viktor Suvorov receives an order, already on Czechoslovakian soil, to raise the morale of his company, he can do it quite simply. “I climbed onto a box labeled ‘Made in USA,’ raised a can of stew above my head… and yelled ‘Hurrah!’ A mighty and joyful ‘Hurrah,’ erupting from a hundred throats, was my answer.” The liberating army received foreign food for the road. “The only Soviet product in our ration,” Suvorov writes, “was vodka.” A can of stew becomes a mighty means of exciting enthusiasm because the soldiers are constantly starving. Hunger, consequently, is not only caused by “objective reasons,” a lack of food, it is used as a powerful means of education.

A necessary element of Soviet life—the system of informing—is revealed in the army as if under a microscope. V. Suvorov describes the briefing of the battalion’s informers just before crossing the border: “Informers are always briefed secretly. But here, right before the border, the Special Department, apparently, received new instructions that had to be urgently conveyed to the executors—the informers. And all around was an open field, and time was short. How could you hide here?” And in the open field, the informers gather in a tight cluster. Everyone can see them. And no one is surprised…

Among the specifically Soviet traits, characteristic of both army and civilian life, the plan holds a special place. At first glance, it seems normal that the plan—the law of Soviet life, present everywhere—is also present in the army. On second thought, upon reflection, it seems strange: army and plan.

Meanwhile, like all other Soviet institutions, the army lives by the plan. The facts cited by V. Suvorov brilliantly demonstrate that in the Soviet Union, the plan has very little to do with economics; it is primarily used as an instrument of control. The military commandant of the city of Kharkov instructs the city patrol: “Production norms: railway station—150 violators; city park—120; airport—80; others—60 each.” And the hunt begins. A patrol that fails to meet the norm is sent to the guardhouse. The soldier’s song sings beautifully: “A soldier walks through the city, along an unfamiliar street, and the whole street is brightened by girls’ smiles.” In reality, a soldier who has received a pass sneaks around, trying to avoid his own comrades who are fulfilling the plan. And where there is a plan, where there is a norm, there is necessarily deception, “chernukha,” and eyewash (“tufta”). The story about the exercises, dubbed “Operation Dnieper,” the story about the construction—during the exercises—of a bridge across the Dnieper, designed only to mislead the superiors, and with the superiors’ consent, are brilliant sketches of Soviet reality, of lies elevated to a principle of life.

Finally, the unprecedented hierarchy of the Soviet system, unseen anywhere else in the world today, manifests itself with particular force in the army. The system of subordination of juniors to seniors, inevitable in every military organization, takes on the character of a caste structure in the Soviet Army, where insurmountable barriers separate one “caste” from another. This structure is supported by the system of awarding military ranks (in civilian life—career advancement), which primarily takes qualification into account.

The occupation of Czechoslovakia, described in the third part, is the logical conclusion of the plot: the army depicted by V. Suvorov, the Soviet man in uniform, underwent the test of a foreign campaign. The task was accomplished: the attempt to reform the socialist system was crushed in the bud. But the army suffered a crushing defeat upon contact with Czechoslovakia: “It was completely unclear to the soldiers why it was necessary to forcibly bring down such a beautiful country to the state of poverty in which we live.” Viktor Suvorov records: many soldiers and young officers “went straight from Czechoslovakia to the Chinese border for re-education. And the liberators were driven to the troop trains like prisoners…” He conveys the thoughts of his officer friends: “We all realized that for the next decade, no matter what happened in the world, no one would dare send us to a country with a higher standard of living.”

12 years after the liberation march through Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Army was sent to carry out its “international duty” in Afghanistan, a country with a lower standard of living. This time, the “liberated” met the “liberators” with gunfire. The flaws of the Soviet Army, faithfully reflecting the flaws of the Soviet system, cannot withstand the test of war on foreign soil. But the war continues, with no end in sight. There are many reasons that prompted the Soviet leadership to commit aggression against Afghanistan. A political reason occupies a prominent place among them. It is said that a people who oppress other peoples cannot be free. The Soviet Army was sent to Afghanistan so that the Soviet people, by oppressing the Afghans, would stop even dreaming of becoming free.

The Liberators’ Tales is a book about the times of Brezhnev. It remains current and topical even in the times of Gorbachev. The same “order” reigns in the tank forces, in all other branches of the Soviet forces, in the Land of Soviets, which maintains the largest army in the world.

Mikhail Heller

Paris, 1986

FOREWORD TO THE FIRST RUSSIAN EDITION

Lenin was an enemy. Not a simple enemy, but a vile, cunning, deeply conspiratorial fiend. Just look at Lenin’s inner circle, those with whom he drank beer in Geneva taverns, with whom he hung out in shanties. All of them: Zinoviev and Kamenev, Trotsky and Tomsky, Rykov and Radek, Bukharin and Krestinsky—turned out to be scum, vile traitors, and despicable saboteurs. All of them inflicted colossal damage on our people. This succeeded only because all of them ended up at the pinnacle of unlimited power. Who brought them there? Lenin. All of Lenin’s “scoundrels” had to be exterminated later: some with a bullet in the back of the head, others with an ice ax to the skull.

“A fetid heap of human refuse”—this is how the world’s most just Soviet court defined Lenin’s closest associates. Who, in that case, was Lenin? He was the center and the peak of this heap. Numerous court proceedings proved irrefutably that everyone who made the revolution with Lenin was an agent of foreign intelligence services. So who was Lenin? He was the ringleader of this vile gang, an espionage resident.

Stalin was an enemy. I won’t even waste paper on proof. The Communist Party proved this to the whole world at its historical congresses. Stalin was also the ringleader of enemies and traitors. Stalin himself exterminated thousands of enemies and spies from his inner circle, but he still could not exterminate all the enemies. Stalin’s closest friend and associate Beria and his gang had to be liquidated after Stalin. But those who carried out the liquidation also turned out to be enemies of our Party and people, scoundrels, debauchers, careerists who had wormed their way in, unprincipled intriguers, volunterists, whom it is even shameful to remember.

Hundreds of millions of people during the times of Lenin and Trotsky, Stalin and Beria, Malenkov and Khrushchev believed that they were serving their homeland, their people. You were mistaken, dear comrades, you were serving the enemies of our people, you were serving vile, insignificant little people, traitors and spies. You were carrying out obviously criminal orders from the enemies of our Fatherland…

And then another epoch arrived. All the scoundrels and careerists were driven out, and a great politician, a great military leader, a great fighter for peace, Chairman of the Council of Defense, laureate of the Lenin Prize for the strengthening of peace among peoples, Marshal of the Soviet Union, four-time Hero of the Soviet Union, Hero of Socialist Labor, bearer of the highest military order “Victory,” Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, rose to the pinnacle of power. It was at this moment that I joined the Soviet Army. Everyone loved Brezhnev, and I loved him. Everyone yelled “hurrah,” and I yelled too. And then, sensing something was wrong, I ran away. Now it turns out that this was the correct decision. It turns out that Leonid Ilyich was indeed a politician of the Leninist type, that is, the peak and center of the fetid human refuse, the ringleader of a criminal gang that was mired in luxury and corruption, driving the country into an economic dead end.

Some are surprised by my insight: how could I have understood that Brezhnev was a scoundrel, at a time when everyone loved him so much? And there is no secret here. I simply calculated it. And if you, my reader, are now serving the new communist leaders, here is my prediction: there will be a time, and very soon, when those whom you serve will take their place in the long column of enemies of our people. Don’t you believe it? Then do the statistics yourself. Dig up the archives of the republic in which you live, look into the archives of your hometown or village, the regiment in which you serve, the factory or collective farm where you work, and you will see that everyone who has ruled, since Lenin’s time, has been an enemy. This follows from the protocols of their meetings and congresses, from the Pravda newspaper. By the way, Pravda was also published by enemies at all times. Here, opposite my writing desk, is a huge portrait of Lenin. Squinting his sly eyes, the leader is reading Pravda. The leader could be put against the wall for this alone, because he is reading anti-Soviet material: at that time, Pravda was published by the hardened fiend Bukharin. Lenin showed a complete lack of revolutionary vigilance and political short-sightedness by reading and praising what the enemies threw at him.

I was a Komsomol member. Out of curiosity, I gathered information about all the leaders of this organization and realized that the organization was always in the hands of enemies: Oskar Ryvkin and Lazar Shatskin, Smorodin and Chaplin, Milchakov and Kosarev, Shelepin and Tyazhelnikov—all eventually turned out to be foreign agents, adventurers, scoundrels. I joined the party, and for the sake of the same interest, I collected information about everyone who bore the title “member of the Politburo.” It turned out that the suicide rate in this dirty gang was higher than in any other social group on our planet, including Parisian prostitutes. I went into the army and discovered with horror that it was created by the proletariat’s worst enemy, Leon Trotsky. Wherever fate threw me, I constantly ended up in organizations of enemies and traitors. I discovered that everyone above us, since Lenin’s time, inevitably turns out to be an enemy in the end. In order not to carry out their criminal orders and not to harm my people, I fled from the enemies.

I have written several books about my life, my country, and its army, and I continue to write. This book is the very first one.

It was published in English in 1981. It then appeared in many languages around the world, even in Japanese. This book has long crossed the “Iron Curtain” and returned to where I fled from. It was published in Polish in the underground printing houses of free, unconquered Poland; it is read in Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Now, finally, the book is coming out in Russian. I have been waiting for this moment for many years. I wrote the book primarily for my compatriots who are still under the power of enemies, sometimes without even suspecting it.

I firmly believe that the day will come when our people will overthrow the enemies and be freed from their power. Now I know that thousands of my compatriots, risking their lives, are waging a persistent struggle against the enemy regime, bringing closer the day when the regime will collapse. I, too, have played a part in this endeavor.

Viktor Suvorov

London, September 1986

HOW I BECAME A LIBERATOR

The Party is our helmsman…

The Central Committee of the Party decided to sharply increase agricultural production. Many smart minds pondered how to implement the Party’s decisions. The first secretary of our regional committee thought about this, too. And along with him, the second secretaries, the third secretaries, the advisers, the consultants, and the assistants all pondered it.

To tell the truth, it was a trivial task. Our climate is like yours in France. We have meter-deep black earth. Fatty black earth—you could spread it on bread instead of butter. We have countless tractors on our collective farms, and even more agronomists. But here’s the trouble—we get no benefit from record harvests! Nothing falls to us from those records! You’ll agree that it couldn’t be otherwise. If we were given even ten percent of what we produced for our labor, we would all instantly become rich. We would become richer than the officials who write instructions for us. And that is inequality, social injustice. And furthermore, if we really did get ten percent, we would glut the country with bread—there would be overproduction. No, it’s better to under-eat than to over-eat. Therefore, the Party decided to sharply increase agricultural production, but in such a way that we, the peasants, would not be interested in it.

Our regional committee secretary thought for a long time. Finally, he came up with something. Or perhaps someone suggested it to him: “Fertilizers!”

Well, that’s a good thing. They decided to increase fertilizer production at the local chemical plant. The plant sells its products to the state, but if they unlock reserves, if they save raw materials and energy, if they work with dedication, if they start a labor watch, then… A meeting was gathered at the chemical plant. The trumpeters puffed out their cheeks, the trumpets shone with brass, the red calico flapped in the wind, and the working class made speeches. Said and done. They saved all winter. And on April 22, they held a volunteer Saturday work day and produced thousands of tons of fertilizer from the saved raw materials. By resolution of the meeting, all these precious tons were transferred to the surrounding collective farms for free. Let there be a harvest! Let our Motherland bloom like a spring garden. Again, the orchestra played hymns, again, speeches were made. Capital correspondents fussed with their cameras, and in the evening, they talked about our chemical plant on the radio news and showed it on television. The regional committee secretary sent a report, and the newspapers praised him and strongly advised everyone to adopt the advanced experience. All chemical plants across the country solemnly swore to also start saving and boost the harvest using the saved raw materials.

The labor holidays ended, and the weekdays followed. In the morning, they called the regional committee directly from the chemical plant: what should they do with the fertilizers? All the tanks were filled with above-plan production. If it was not immediately taken away, the plant would stop. It must be milked on time, like a cow. Production could not be stopped—they wouldn’t get a bonus for that. Giving the above-plan production to the state was also impossible—no rail tankers were planned for its removal. And in the meantime, new raw material kept arriving at the plant—where could they put it?

They called the district committees from the regional committee, and from there to the collective farm boards: take your gift, and hurry up.

The news that our collective farm had been given 150 tons of liquid fertilizer for free did not cheer up or gladden our chairman. We were ordered to pick up the gift in twenty-four hours. And we only have seventeen trucks on our collective farm, and only three of them have tankers. One of them carried milk, the other carried water. They weren’t quite suitable for transporting fertilizer. Only one tanker remained—the one for gasoline. That was a very old truck, a GAZ-51, from the year they made the cabin doors out of wood—from plywood. It was 73 kilometers to the city. Given the state of our roads, that meant five hours there and five hours back. Only one and a half tons fit in the barrel. And I was the driver of that truck.

“Listen, Vitya,” the chairman says. “If you don’t sleep for 24 hours, if the batteries in your wreck don’t die, if the radiator doesn’t burst from steam, if the gearbox doesn’t seize up, if you don’t get stuck in the mud, you’ll make two trips in a day and bring back three tons. But in 24 hours, you need to make not two trips, but one hundred!”

“Understood,” I said.

“That’s not all,” he says. “We have a problem with gasoline. I’ll give you gasoline for three trips, of course, but for the remaining ninety-seven, you do as you please. Even push your truck with your rear.”

“Understood,” I said.

“I’m counting on you, Vitya. If you don’t make a hundred trips, they’ll fire me as chairman. And I’ll wring your neck. Don’t doubt it.”

I didn’t doubt it, did I?

“Is everything clear?”

“No, not everything. Say I make a hundred trips… without fuel, where should I put this fertilizer?”

The chairman cast a puzzled glance over the wide collective farm yard. Indeed, where? Lenin happened to be born in April, which is why above-plan production is done at Leninist volunteer Saturdays precisely in April. We didn’t know exactly when to apply this fertilizer to the soil, but definitely not in April. So where should it be stored? 150 tons of smelly, poisonous liquid?

“Tell you what,” the chairman says, “you hurry off to the city and see what people are doing. The Party didn’t give this puzzle to just us. Other collective farms have the same problem on their agenda. See what people do, and you do the same. Surely there’s a bright mind in our region that will come up with the solution. Our people are talented. Good luck, and don’t come back without a victory. If you don’t win, they’ll wring my neck, and I’ll wring yours. Don’t doubt that.”

And did I doubt it?

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.