Description

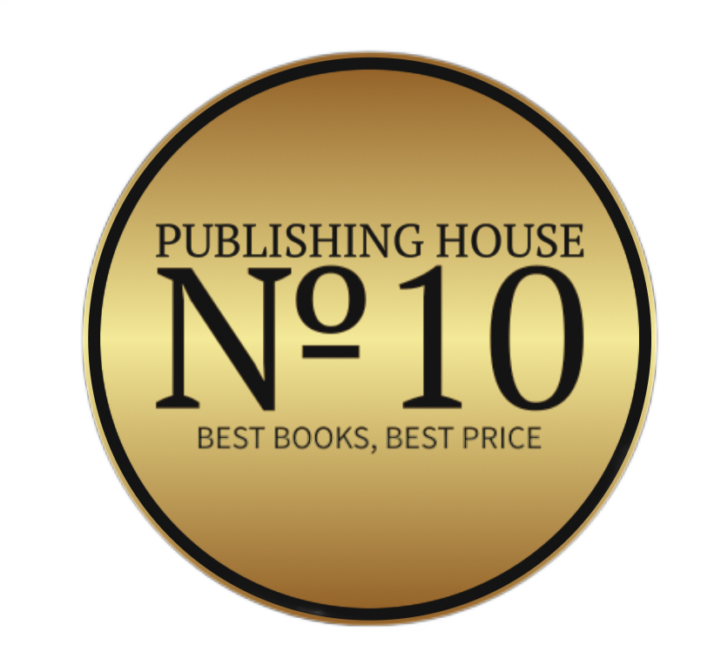

The story is narrated by Dmitry Sanin, a nobleman and landowner, who looks back on events that happened thirty years prior during his travels in Germany.

One day, while passing through Frankfurt, the protagonist falls in love with Gemma, the daughter of a confectionery owner. He proposes to her and begins to make plans for their life together. To get money for their new life, he decides to sell his estate. For this purpose, he travels to Wiesbaden to meet the buyer—a wealthy and young Russian beauty named Marya Nikolaevna Polozova.

Unable to resist Marya Nikolaevna’s strong personality, Sanin forgets his German fiancée. The author describes the development of the protagonist’s relationships, first with Gemma and then with Polozova, tracing the emergence of sincere, true love in one case, and passion in the other. This passion ultimately breaks the life of the noble, but indecisive and weak-willed, protagonist of the novella.

Turgenev didn’t invent the story’s beginning. As German professor Friedländer recalled in “Vestnik Evropy” (1906, No. 10, pp. 830-831):

“Just like Sanin, Turgenev, while still a young man returning home from Italy, was asked for help by a frightened, beautiful girl in a confectionery shop in Frankfurt am Main. Her brother had fallen into a deep faint. Only, this wasn’t an Italian family, but a Jewish one, and the sick boy had two sisters, not just one. Turgenev then overcame his sudden infatuation with the girl by leaving quickly.”

It’s interesting that the figure of the noblewoman Polozova is a figurative (what’s called “personified”) condemnation of “vulgar liberalism.” She lures one into slavery with the promise of absolute freedom. She begins with declarations about how she respects individual rights, and ends by completely trampling them and deriving pleasure from it.

Browse the table of contents, check the quotes, read the first chapter, find out which famous book it is similar to, and buy “Spring Torrents” on Amazon directly from our page.

Read the Full Text Online: The Torrents of Spring by Ivan Turgenev

I

Merry years,

Happy days —

Like spring torrents

They have rushed by!

From an old romance.

…At around two o’clock in the morning, he returned to his study. He dismissed the servant who had lit the candles, and, throwing himself into an armchair by the fireplace, covered his face with both hands.

Never before had he felt such fatigue — both physical and mental. He had spent the whole evening with pleasant ladies, with educated gentlemen; some of the ladies were beautiful, almost all the gentlemen were distinguished by their intelligence and talents — he himself had conversed very successfully and even brilliantly… and yet, never before had that “taedium vitae” (weariness of life), which the Romans already spoke of, that “aversion to life” — with such an irresistible force taken possession of him, choked him. If he had been a little younger, he would have wept from anguish, boredom, irritation: a bitter, burning acridity, like the bitterness of wormwood, filled his whole soul. Something persistently hateful, repellently heavy surrounded him on all sides, like an autumn, dark night; and he didn’t know how to get rid of this darkness, this bitterness. There was no hope of sleep: he knew he wouldn’t fall asleep.

He began to reflect… slowly, languidly, and angrily.

He reflected on the vanity, futility, and vulgar falseness of all things human. All ages gradually passed before his mind’s eye (he himself had recently turned fifty-two) — and not one found mercy before him. Everywhere it was the same eternal pouring from empty to void, the same treading water, the same half-conscientious, half-conscious self-delusion — whatever keeps the child amused, as long as it doesn’t cry — and then suddenly, like a bolt from the blue, old age would descend — and with it that constantly growing, all-corroding and undermining fear of death… and plunge into the abyss! It’s still good if life plays out that way! Otherwise, perhaps, before the end, infirmities and sufferings will spread like rust over iron… The sea of life did not appear to him covered with stormy waves, as poets describe — no; he imagined this sea immaculately smooth, motionless, and transparent down to its darkest bottom; he himself sits in a small, shaky boat — and there, on this dark, silty bottom, like enormous fish, barely visible are hideous monsters: all worldly ailments, diseases, sorrows, madness, poverty, blindness… He looks — and behold, one of the monsters separates from the darkness, rises higher and higher, becomes ever more distinct, ever more repellently distinct… Another moment — and the boat supported by it will overturn! But then it seems to dim again, it moves away, sinks to the bottom — and lies there, barely stirring its fins… But the appointed day will come — and it will overturn the boat.

He shook his head, jumped up from the armchair, walked around the room once or twice, sat down at his writing desk, and, pulling out one drawer after another, began rummaging through his papers, among old, mostly women’s, letters. He didn’t know why he was doing this, he wasn’t looking for anything — he simply wanted to get rid of the thoughts tormenting him through some external occupation. Unfolding several letters at random (in one of them he found a dried flower tied with a faded ribbon), he only shrugged his shoulders and, glancing at the fireplace, tossed them aside, probably intending to burn all this unnecessary clutter. Hastily thrusting his hands into one drawer, then another, he suddenly opened his eyes wide and, slowly pulling out a small octagonal box of an old design, slowly lifted its lid. In the box, under a double layer of yellowed cotton paper, lay a small garnet cross.

For a few moments, he examined this cross with bewilderment — and then suddenly let out a faint cry… Neither regret nor joy was depicted on his features. A similar expression appears on a person’s face when they suddenly encounter another person whom they had lost sight of long ago, whom they once dearly loved, and who now unexpectedly appears before their eyes, still the same — and entirely changed by the years.

He stood up and, returning to the fireplace, sat down in the armchair again — and again covered his face with his hands… “Why today? Why precisely today?” he thought, and he remembered much from the long-past…

This is what he remembered…

But first, his full name must be stated. His name was Sanin, Dmitry Pavlovich.

This is what he remembered:

The year was 1840, summer. Sanin had just turned twenty-two, and he was in Frankfurt, on his way back from Italy to Russia. He was a man of modest means, but independent, almost without family. After the death of a distant relative, he came into several thousand rubles — and he decided to spend them abroad before entering service, before finally donning that official yoke (burden of government service) without which a secure existence became inconceivable to him. Sanin precisely carried out his intention and managed his affairs so skillfully that on the day of his arrival in Frankfurt, he had exactly enough money to reach Petersburg. In 1840, there were very few railways; gentlemen tourists traveled by diligence. Sanin took a seat in the “beywagen” (an extra, less comfortable section of the diligence); but the diligence wasn’t departing until eleven o’clock in the evening. There was plenty of time left. Fortunately, the weather was excellent — and Sanin, after dining at the then-famous “White Swan” hotel, went for a stroll around the city. He went to see Dannecker’s Ariadne, which he didn’t much care for, visited Goethe’s house, though he had only read “Werther” of his works — and that in a French translation; he walked along the banks of the Main, felt bored, as a respectable traveler should; finally, at six o’clock in the evening, tired, with dusty feet, he found himself in one of Frankfurt’s most insignificant streets. He could not forget this street for a long time afterward. On one of its few houses, he saw a sign: “Giovanni Roselli’s Italian Confectionery” announced itself to passersby. Sanin went inside to drink a glass of lemonade; but in the first room, where, behind a modest counter, on the shelves of a painted cabinet, reminiscent of an apothecary, stood several bottles with golden labels and as many glass jars with rusks, chocolate wafers, and lollipops — in this room, there wasn’t a soul; only a gray cat squinted and purred, kneading its paws, on a high wicker chair by the window, and, glowing brightly in the slanting ray of the evening sun, a large ball of red yarn lay on the floor next to an overturned carved wooden basket. A vague noise was heard in the adjoining room. Sanin stood for a moment and, letting the doorbell ring completely, raised his voice and said: “Is there no one here?” At the same instant, the door from the adjoining room opened — and Sanin was involuntarily astonished.

II

Into the confectionery, a girl of about nineteen, with dark curls scattered over her bare shoulders, and outstretched bare arms, rushed impulsively. Upon seeing Sanin, she immediately darted towards him, seized his hand, and pulled him along, saying in a breathless voice: “Quick, quick, this way, save him!” Not from unwillingness to obey, but simply from an excess of astonishment, Sanin did not immediately follow the girl and seemed rooted to the spot: he had never in his life seen such a beauty. She turned to him and with such despair in her voice, in her gaze, in the movement of her clenched hand convulsively raised to her pale cheek, she uttered: “Come on, come on!” — that he immediately rushed after her through the open door.

In the room he entered, following the girl, lay a boy of about fourteen, strikingly similar to the girl, obviously her brother, on an old-fashioned horsehair sofa. He was entirely white — white with yellowish tints, like wax or ancient marble. His eyes were closed, a shadow from his thick black hair fell like a blotch on his seemingly petrified forehead, on his motionless thin eyebrows; clenched teeth were visible from under his bluish lips. He seemed not to be breathing; one hand had dropped to the floor, the other he had thrown back behind his head. The boy was dressed and buttoned up; a tight tie constricted his neck.

The girl cried out and rushed to him.

“He’s dead, he’s dead!” she cried, “Just now he was sitting here, talking to me — and suddenly he fell and became motionless… My God! Can nothing be done? And Mama isn’t here! Pantaleone, Pantaleone, what about the doctor?” she added suddenly in Italian. “Did you go for the doctor?”

“Signora, I didn’t go, I sent Luisa,” a hoarse voice sounded from behind the door, and into the room, hobbling on crooked legs, came a small old man in a purple frock coat with black buttons, a high white tie, nankeen (a type of durable cotton fabric) short breeches, and blue woolen stockings. His tiny face completely disappeared under a whole mass of gray, iron-colored hair. Rising steeply upwards on all sides and falling back in dishevelled wisps, they gave the old man’s figure a resemblance to a crested hen — a resemblance all the more striking because beneath their dark gray mass, all that could be discerned was a pointed nose and round yellow eyes.

“Luisa will run faster, and I cannot run,” the old man continued in Italian, alternately lifting his flat, gout-afflicted feet, shod in high boots with bows, “but I brought water.”

With his dry, gnarled fingers, he clutched the long neck of the bottle.

“But Emil will die in the meantime!” exclaimed the girl and stretched out her hands to Sanin. “Oh, my lord, oh, mein Herr (my sir)! Can you not help?”

“One must bleed him — it’s a stroke,” remarked the old man, who bore the name Pantaleone.

Although Sanin had not the slightest idea about medicine, he did know one thing for certain: strokes do not happen to fourteen-year-old boys.

“It’s a faint, not a stroke,” he said, turning to Pantaleone. “Do you have brushes?”

The old man raised his tiny face.

“What?”

“Brushes, brushes,” Sanin repeated in German and French. “Brushes,” he added, mimicking cleaning his clothes.

The old man finally understood him.

“Ah, brushes! Spazzette (brushes)! How could there be no brushes!”

“Bring them here; we’ll take off his coat — and start rubbing him.”

“Good… Benone (very good)! And should we pour water on his head?”

“No… later; now go quickly for the brushes.”

Pantaleone put the bottle on the floor, ran out, and immediately returned with two brushes, one hairbrush and one clothes brush. A curly poodle accompanied him and, vigorously wagging its tail, curiously looked at the old man, the girl, and even Sanin — as if wanting to know what all this commotion meant?

Sanin quickly took off the coat of the boy lying down, unbuttoned his collar, rolled up the sleeves of his shirt — and, armed with a brush, began to rub his chest and arms with all his might. Pantaleone just as diligently rubbed the other — hairbrush — on his boots and trousers. The girl knelt by the sofa and, holding his head with both hands, without blinking an eyelid, stared intently at her brother’s face.

Sanin himself was rubbing — and at the same time glancing at her from the side. My God! What a beauty she was!

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.