A True Incident

One April afternoon in 1880, Andrei, the doorman, entered my study and mysteriously informed me that some gentleman had appeared at the editorial office and was urgently requesting an audience with the editor.

“He must be a civil servant, sir,” Andrei added, “with a cockade…”

“Ask him to come another time,” I said. “I’m busy today. Tell him the editor only sees visitors on Saturdays.”

“He came the day before yesterday too, asking for you. Says it’s an important matter. He’s pleading, almost crying. Says he’s not free on Saturday… Shall I let him in?”

I sighed, put down my pen, and began to wait for the gentleman with the cockade. Aspiring writers, and indeed all people uninitiated into editorial secrets, who feel a sacred tremor at the word “editorial office,” tend to make you wait for quite some time. After the editor’s “show him in,” they cough for a long time, blow their noses for a long time, slowly open the door, enter even more slowly, and thus consume a good deal of time. The gentleman with the cockade, however, didn’t keep me waiting. No sooner had Andrei closed the door than I saw in my study a tall, broad-shouldered man, holding a paper parcel in one hand and a cap with a cockade in the other.

The man who had so persistently sought an audience with me plays a very prominent role in my story. It is necessary to describe his appearance.

As I’ve already said, he is tall, broad-shouldered, and stout, like a good working horse. His entire body exudes health and strength. His face is rosy, his hands large, his chest broad and muscular, his hair thick, like a healthy boy’s. He’s approaching forty. He’s dressed tastefully and in the latest fashion, in a brand-new, recently tailored tweed suit. On his chest is a large gold chain with charms, and on his little finger, a diamond ring glitters with tiny, bright stars. But most importantly, and what is so vital for any hero of a novel or story, however insignificant, he is extraordinarily handsome. I am neither a woman nor an artist. I understand little of male beauty, but the gentleman with the cockade made an impression on me with his appearance. His large, muscular face has remained forever in my memory. On this face, you will see a truly Grecian nose with a slight hump, thin lips, and fine blue eyes, in which kindness shines, and something else that is difficult to find a suitable name for. This “something” can be noticed in the eyes of small animals when they are longing or when they are in pain. Something pleading, childlike, enduring meekly… Cunning and very intelligent people do not have such eyes.

His whole face radiates simplicity, a broad, simple nature, truth… If it’s not a lie that the face is the mirror of the soul, then on the first day of my meeting with the gentleman with the cockade, I could have given my word of honor that he was incapable of lying. I could even have wagered on it.

Whether I would have lost the wager or not, the reader will see later.

His chestnut hair and beard are thick and soft as silk. They say that soft hair is a sign of a soft, gentle, “silken” soul… Criminals and evil, stubborn characters mostly have coarse hair. Whether this is true or not, the reader will again see later… Neither his facial expression nor his beard—nothing in the gentleman with the cockade is as soft and gentle as the movements of his large, heavy body. In these movements, breeding, lightness, grace, and even—forgive the expression—a certain femininity are evident. My hero would not need much effort to bend a horseshoe or flatten a sardine tin in his fist, yet none of his movements betray his physical strength. He takes hold of a doorknob or a hat as if it were a butterfly: gently, carefully, lightly touching with his fingers. His steps are silent, his handshakes weak. Looking at him, you forget that he is mighty as Goliath, that with one hand he can lift what five editorial Andreis could not. Looking at his light movements, it’s hard to believe that he is strong and heavy. Spencer might have called him a model of grace.

Entering my study, he became flustered. His delicate, sensitive nature was probably shocked by my frowning, displeased look.

“Forgive me, for God’s sake!” he began in a soft, rich baritone. “I’m bursting in on you at an inconvenient time and making you make an exception for me. You are so busy! But you see, Mr. Editor, the thing is: I’m leaving for Odessa tomorrow on a very important matter… If I had the opportunity to postpone this trip until Saturday, believe me, I wouldn’t have asked you to make an exception for me. I bow to rules, because I love order…”

“How much he talks, though!” I thought, reaching for my pen and thereby indicating that I had no time. (Visitors had become terribly tiresome to me then!)

“I’ll only take one minute of your time!” my hero continued in an apologetic voice. “But first of all, allow me to introduce myself… Bachelor of Laws Ivan Petrovich Kamyshev, former investigative magistrate… I do not have the honor of belonging to the writing fraternity, but, nevertheless, I have come to you with purely literary aims. Before you stands one who wishes to join the ranks of beginners, despite being almost forty. But better late than never.”

“Very glad… How can I be of service?”

The aspiring writer sat down and continued, looking at the floor with his pleading eyes:

“I’ve brought you a small story that I’d like to publish in your newspaper. I’ll tell you frankly, Mr. Editor: I wrote my story not for authorial fame or for sweet sounds… I’m too old for those good things. I’m embarking on the path of authorship simply for mercenary motives… I want to earn something… I currently have absolutely no occupation. I was, you see, an investigative magistrate in S— district, served for over five years, but gained neither capital nor preserved my innocence…”

Kamyshev looked up at me with his kind eyes and chuckled softly.

“A tiresome service… I served and served, then threw up my hands and quit. I have no occupation now, almost nothing to eat… And if you, overlooking its merits, publish my story, you will do me more than a favor… You will help me… A newspaper is not a charity, not a hospice… I know that, but… please, be so kind…”

“You’re lying!” I thought.

The charms and the ring on his little finger didn’t quite fit with writing for a crust of bread, and a barely noticeable cloud, perceptible only to an experienced eye, passed over Kamyshev’s face—the kind of cloud seen only on the faces of people who rarely lie.

“What’s the plot of your story?” I asked.

“The plot… How can I tell you? The plot isn’t new… Love, murder… Well, you’ll read it, you’ll see… ‘From the Notes of an Investigative Magistrate’…”

I probably winced, because Kamyshev blinked in embarrassment, fidgeted, and said quickly:

“My story is written in the style of former investigative magistrates, but… in it you will find truth, reality… Everything depicted in it, everything from cover to cover, happened before my very eyes… I was both an eyewitness and even a participant.”

“It’s not about truth… You don’t necessarily need to see something to describe it… That’s not important. The point is, our poor public has long since grown weary of Gaboriau and Shklyarevsky. They’re tired of all these mysterious murders, the cunning machinations of detectives, and the extraordinary resourcefulness of interrogating magistrates. The public, of course, varies, but I’m talking about the public that reads my newspaper. What’s your story called?”

“Drama on the Hunt.”

“Hmm… Not serious, you know… And, frankly speaking, I’ve accumulated such a mass of material that it’s absolutely impossible to accept new works, even if they have undeniable merits…”

“But please, do accept my work… You say it’s not serious, but… it’s difficult to judge a work without seeing it… And can you really not allow that investigative magistrates can also write seriously?”

Kamyshev stammered all this, twirling a pencil between his fingers and looking at his feet. He finished by becoming greatly embarrassed and blinking. I felt sorry for him.

“Alright, leave it,” I said. “Only I can’t promise you that your story will be read anytime soon. You’ll have to wait…”

“Long?”

“I don’t know… Come back in, say, two or three months…”

“Quite long… But I dare not insist… Let it be as you wish…”

Kamyshev stood up and picked up his cap.

“Thank you for the audience,” he said. “I’ll go home now and feed myself on hopes. Three months of hopes! But, I’ve probably tired you out. I have the honor to bow!”

“Just one moment,” I said, flipping through his thick notebook, filled with small handwriting. “You’re writing here in the first person… So, by ‘investigative magistrate’ here, you mean yourself?”

“Yes, but under a different surname. My role in this story is somewhat scandalous… It’s awkward to use my own name… So, in three months?”

“Yes, probably not sooner…”

“Be well!”

The former investigative magistrate bowed gallantly, carefully took hold of the doorknob, and disappeared, leaving his work on my table. I took the notebook and put it in my desk.

The handsome Kamyshev’s story rested in my desk for two months. One day, leaving the editorial office for my dacha, I remembered it and took it with me.

Sitting in the train car, I opened the notebook and began to read from the middle. The middle interested me. That same evening, despite my lack of leisure, I read the entire story from beginning to the word “The End,” written in a sprawling hand. That night, I read the story once more, and at dawn, I walked back and forth on the terrace, rubbing my temples as if I wanted to wipe away a new, suddenly appearing, tormenting thought… And the thought was indeed tormenting, unbearably sharp… It seemed to me that I, neither an investigative magistrate nor, even less so, a professional psychologist, had discovered a terrible secret about a person, a secret that was none of my business… I walked the terrace, trying to convince myself not to believe my discovery…

Kamyshev’s story did not make it into my newspaper for the reasons stated at the end of my conversation with the reader. I will meet the reader once more. For now, as I take my leave, I offer Kamyshev’s story for their reading.

This story is nothing out of the ordinary. It has many lengthy passages, quite a few rough edges… The author has a weakness for effects and strong phrases… It’s clear that he’s writing for the first time in his life, with an unaccustomed, untrained hand… But still, his story reads easily. There is a plot, and a meaning too, and, most importantly, it is original, very characteristic, and what is called sui generis (of its own kind, Latin). It also has some literary merits. It’s worth reading… Here it is.

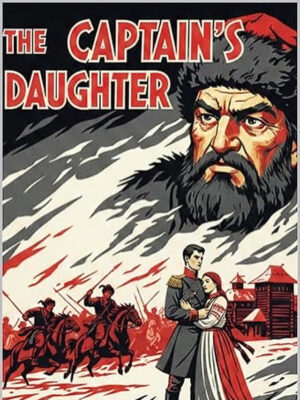

From the Notes of an Investigative Magistrate

Chapter I

“The husband killed his wife! Oh, how foolish you are! Give me some sugar at last!”

This shout woke me up. I stretched and felt a heaviness, a malaise, in all my limbs… One can get a limb numb, but this time it felt as if my entire body, from head to toe, was numb. An afternoon nap in a stuffy, parching atmosphere, amidst the buzzing of flies and mosquitoes, has a debilitating, not invigorating, effect. Broken and drenched in sweat, I got up and went to the window. It was six o’clock in the evening. The sun was still high and burned with the same intensity as three hours earlier. There was still a long time until sunset and coolness.

“The husband killed his wife!”

“Stop lying, Ivan Demianych!” I said, flicking Ivan Demianych’s nose lightly. “Husbands kill wives only in novels and in the tropics, where African passions boil, my dear. For us, horrors like burglaries or living under false pretenses are quite enough.”

“Burglaries…” Ivan Demianych drawled through his hooked nose. “Oh, how foolish you are!”

“But what can one do, my dear? How are we, humans, to blame that our brains have limits? However, Ivan Demianych, it’s not a sin to be a fool in such a temperature. You are clever, but I bet even your brains have turned soggy and stupid from this heat.”

My parrot is not called “Polly” or any other bird name, but Ivan Demianych. He got this name entirely by chance. One day, my servant Polikarp, while cleaning his cage, suddenly made a discovery without which my noble bird would still be called “Polly”… The lazy fellow was suddenly struck by the thought that my parrot’s nose was very similar to the nose of our village shopkeeper, Ivan Demianych, and from that moment on, the parrot was forever stuck with the name and patronymic of the long-nosed shopkeeper. With Polikarp’s light hand, the entire village christened my strange bird Ivan Demianych. By Polikarp’s will, the bird became a “person,” and the shopkeeper lost his real nickname: he would, until the end of his days, be referred to by the villagers as “the investigator’s parrot.”

I bought Ivan Demianych from the mother of my predecessor, the judicial investigator Pospelov, who had died shortly before my appointment. I bought him along with antique oak furniture, kitchen clutter, and all the household effects left by the deceased. My walls are still adorned with photographs of his relatives, and above my bed still hangs a portrait of the owner himself. The deceased, a thin, sinewy man with a reddish mustache and a large lower lip, sits, eyes bulging, in a faded walnut frame and never takes his eyes off me the entire time I lie on his bed… I haven’t removed a single photograph from the walls; in short—I left the apartment exactly as I found it. I am too lazy to bother with my own comfort, and I don’t mind not only the dead hanging on my walls, but even the living, if the latter so desire. (I beg the reader’s pardon for such expressions. Kamyshev’s unfortunate novella is rich with them, and if I did not cross them out, it was only because I deemed it necessary, in the interest of characterizing the author, to print his novella in toto (without omissions, Latin). — A. Ch.)

Ivan Demianych was as stuffy as I was. He ruffled his feathers, spread his wings, and loudly shouted phrases he had learned from my predecessor Pospelov and Polikarp. To occupy my afternoon leisure, I sat in front of the cage and observed the parrot’s movements, diligently searching for and not finding a way out of the torment caused by the stuffiness and the insects inhabiting his feathers… The poor creature seemed very unhappy…

“And at what time do they wake up?” I heard a bass voice from the anteroom…

“It varies!” Polikarp’s voice replied. “Sometimes he wakes at five, and sometimes he sleeps until morning… You know, there’s nothing to do…”

“Are you their valet?”

“A servant. Now, don’t bother me, be quiet… Can’t you see I’m reading?”

I peered into the anteroom. There, on a large red chest, lay my Polikarp, as usual, reading some book. His sleepy, never-blinking eyes fixed on the book, he moved his lips and frowned. Apparently, the presence of a stranger, a tall, bearded peasant, standing in front of the chest and vainly trying to strike up a conversation, irritated him. At my appearance, the peasant took a step back from the chest and stood at attention like a soldier. Polikarp made a displeased face and, without taking his eyes off the book, slightly raised himself.

“What do you want?” I asked the peasant.

“I’m from the Count, Your Honor. The Count sends his regards and asked you to come to him at once, sir…”

“Has the Count arrived?” I was surprised.

“Precisely so, Your Honor… Arrived last night… Here’s the letter, please…”

“The devils brought him again!” my Polikarp grumbled. “Two summers we lived peacefully without him, and now he’ll start a pigsty in the district again. There’ll be no end to the shame.”

“Be quiet, no one asked you!”

“No need to ask me… I’ll tell you myself. You’ll be coming back from him drunk and in a mess again, swimming in the lake, just as you are, in full costume… Then clean it! You won’t clean it in three days!”

“What is the Count doing now?” I asked the peasant…

“He was just sitting down to dinner when they sent me to you… Before dinner, they were fishing in the bathhouse, sir… How shall I answer?”

I opened the letter and read the following:

“My dear Lecoq! If you are still alive, well, and haven’t forgotten your most drunken friend, then, without a moment’s delay, put on your clothes and rush to me. I only arrived last night, but I am already dying of boredom. The impatience with which I await you knows no bounds. I wanted to come for you myself and take you to my den, but the heat has bound all my limbs. I sit in one place and fan myself. Well, how are you living? How is your cleverest Ivan Demianych? Still warring with your pedant Polikarp? Come quickly and tell me.

Your A. K.”

One didn’t need to look at the signature to recognize the large, ugly handwriting of my friend, Count Aleksey Korneev, rarely writing when drunk. The brevity of the letter, its attempt at playfulness and vivacity, indicated that my simple-minded friend had torn up a lot of stationery before he managed to compose this letter.

The letter lacked the pronoun “which” and carefully avoided participles — both of which the Count rarely managed in one sitting.

“How shall I answer?” the peasant repeated.

I didn’t answer that question immediately, and any fastidious person would have hesitated in my place. The Count loved me and sincerely pushed himself upon me as a friend, but I felt nothing akin to friendship for him and didn’t even like him; it would therefore have been more honest to simply refuse his friendship once and for all, rather than go to him and be hypocritical. Besides, going to the Count meant immersing myself once again in a life that my Polikarp called a “pigsty” and which, two years ago, throughout the Count’s stay before his departure for St. Petersburg, undermined my robust health and dried up my brain. This dissolute, unusual life, full of effects and drunken frenzy, did not manage to undermine my body, but it did make me known throughout the entire province… I was popular…

Reason told me the absolute truth, the blush of shame for the recent past spread across my face, my heart contracted with fear at the mere thought that I wouldn’t have the courage to refuse the trip to the Count, but I didn’t hesitate for long. The struggle lasted no more than a minute.

“Bow to the Count,” I told the messenger, “and thank him for remembering me… Tell him I’m busy and that… Tell him that I…”

And at the very moment when a decisive “no” was about to escape my tongue, a heavy feeling suddenly overwhelmed me… A young man, full of life, strength, and desires, cast by fate into a rural wilderness, was seized by a feeling of longing, of loneliness…

I remembered the Count’s garden with the luxury of its cool conservatories and the twilight of its narrow, abandoned alleys… These alleys, protected from the sun by a canopy of green, intertwining branches of old lime trees, know me… They also know the women who sought my love and the twilight… I remembered the luxurious living room, with the sweet languor of its velvet sofas, heavy curtains and carpets, soft as down, with the languor that young, healthy animals so love… My drunken daring came to mind, knowing no bounds in its breadth, satanic pride, and contempt for life. And my large body, tired from sleep, again craved movement…

“Tell him I’ll come!”

The peasant bowed and left.

“If I had known, I wouldn’t have let him in, the devil!” Polikarp grumbled, quickly and aimlessly flipping through the book.

“Leave the book and go saddle Zorka!” I said sternly. “Quickly!”

“Quickly… Indeed, without fail… So I’ll just go and run… If only it were for a real purpose, but no, he’s going to break the devil’s horns!”

This was said in a half-whisper, but loud enough for me to hear. The lackey, having whispered his impudence, stood at attention before me and, with a contemptuous smirk, awaited my angry outburst, but I pretended not to hear his words. My silence is the best and sharpest weapon in battles with Polikarp. This contemptuous disregard of his poisonous words disarms him and deprives him of ground. It acts as a punishment more effectively than a slap on the back of the head or a stream of curses… When Polikarp went out to the yard to saddle Zorka, I looked into the book I had interrupted him from reading… It was “The Count of Monte Cristo,” a terrifying novel by Dumas… My civilized fool reads everything, from pub signs to Auguste Comte, who lies in my chest with other unread, abandoned books of mine; but out of the entire mass of printed and written material, he recognizes only terrible, powerfully affecting novels with noble “gentlemen,” poisons, and underground passages; everything else he has christened “nonsense.” I will have to speak of his reading in the future, but now — to ride! A quarter of an hour later, the hooves of my Zorka were already raising dust on the road from the village to the Count’s estate. The sun was close to its rest, but the heat and stuffiness were still palpable… The heated air was motionless and dry, despite the fact that my road lay along the bank of a huge lake… To my right, I saw the mass of water, to my left, the young, spring foliage of the oak forest caressed my gaze, and meanwhile, my cheeks experienced the Sahara.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.