Bulgakov and His “Margaritas”

Two women (Elena Shilovskaya and Lyubov Belozerskaya) considered themselves the widows of Mikhail Afanasyevich, and probably another dozen saw themselves as his muses and the prototypes for Margarita. Only Bulgakov’s first wife, Tatyana Lappa, remained in the shadows for a long time…

On our website you can buy this book via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

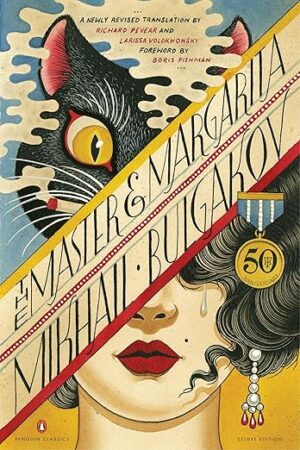

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

Page Count: 448Year: 1967Products search Imagine 1930s Moscow — a city constrained by bureaucracy, shortages, and state-enforced atheism — is suddenly visited by Satan himself, in the guise of Professor Woland, accompanied by his infernal retinue, including the absurdly dressed Koroviev and the massive, talking cat Behemoth. Woland’s visit is a devilish inspection and a session of black […]

€11.00 Login to Wishlist

Margarita Smirnova

Bulgakov had been long gone when The Master and Margarita was finally published in the magazine Moskva. Margarita Petrovna Smirnova, an elderly but still wonderfully beautiful woman, read it and gasped, “But this is about me! What year was that? ’36, or ’37, or perhaps ’38?”

That day, she was walking unhurriedly along Meshchanskaya Street, enjoying an unexpected freedom: the children were at the dacha, and her husband was on a business trip. It smelled of spring, the sun was shining, everything around was ringing and cheerful, and Margarita, having finally exchanged her heavy fur coat for a smart overcoat, walked lightly. In one hand, covered with a long silk glove, she carried a branch of mimosa; in the other, a handbag with a yellow bead-embroidered letter “M.” “Wait a minute!” a man took her elbow. “Give me a chance to introduce myself! My name is Mikhail Bulgakov.” Margarita Petrovna took in his appearance: short, blue eyes, a nervous and expressive face, like an actor’s. The conversation started naturally—as if the two had known each other all their lives and parted only yesterday. They walked, oblivious to the city, and passed the side-street several times where Margarita needed to turn toward home. They stood on the embankment. Facing the wind, she said that she loved standing on the bow of a ship—it was like flying over the water, and she felt so good, so playful… Then they talked about modern literature, and about spring, and how he seemed to have seen her a few years ago in Batumi (“That’s true, I was there with my husband”), and about her sad eyes… Margarita Petrovna confessed that her husband, a railway inspector, was a boring man and endlessly alien to her.

They arranged to meet a week later. She entered her house, looked around it as if not recognizing it, and glanced out the window: Bulgakov was standing in the street, his eyes searching the floors. All week, Margarita Petrovna walked around as if in a fog. She decided it must be stopped before it was too late! “I will never forget you,” a saddened Bulgakov told her goodbye. He stayed put, and Margarita walked away…

Maria and Lyubov

Maria Georgievna Nesterenko kept the magazine Moskva in a prominent place and, rereading the Master’s story about how Margarita came to visit him in his semi-basement on the Arbat, recognized every little detail and rejoiced: “How sweet that Maka described our romance!”

However, in life, everything was the opposite: Marusya Nesterenko herself lived in the semi-basement, and Bulgakov came to her. From the street, one had to walk through the courtyard, past her three ground-level windows. And Marusya always recognized who was coming by their shoes. Bulgakov often tapped the toe of his shoe on the glass, and she would go to open the door. She called him Maka. However, everyone called Bulgakov that back then—thanks to his then-wife, Lyubov Evgenievna Belozerskaya.

“A brilliant woman, but Maka is unhappy with her,” Marusya believed. Belozerskaya was witty, sociable, hospitable, and flirtatious. She was always passionate about something: sometimes horseback riding, sometimes automobiles, and there were always jockeys milling about the house… But Bulgakov was unsociable and mostly languished—he was not being published, his plays were banned, and the newspapers constantly started campaigns against him. It ended in phobias: Bulgakov was afraid of the street, the dark, or dampness… Once he crawled around on all fours, wearing a dressing gown and a nightcap, with a kerosene lamp in his hands—he constantly felt the apartment needed to be dried out. Marusya came in, and Mikhail Afanasyevich said, “I beg you, don’t tell Lyuba.” He was afraid his wife would laugh at him with her guests. The Bulgakovs’ telephone hung above his writing desk, and Belozerskaya constantly chatted, distracting her husband from writing. “Lyuba, this is impossible, I am working!” he once said. And she replied, “It’s fine, you’re not Dostoevsky”…

… “Nonsense,” said the aging but still very worldly Lyubov Evgenievna Belozerskaya when she was told that Marusya Nesterenko considered herself the prototype for Bulgakov’s Margarita. “Maka never took her seriously”… Belozerskaya knew perfectly well which woman was actually described in the novel: green eyes with a slight “slant,” black arched eyebrows, skin that seemed to glow from within, and a wild temper, and laughter—that was a portrait of Lyubov Evgenievna herself in her youth! And it was her that Maka loved with abandon when he started writing his main book!

Elena Sergeevna

Elena Sergeevna—Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov’s third and final wife—did not need to wait for the publication in the magazine Moskva. She read The Master and Margarita as it was being written, and eventually simply learned the novel by heart. How could it be otherwise, when the book was written about her! Mishenka described everything with almost documentary precision: Elena Sergeevna lived a life of luxury, never denied anything, never touching a kerosene stove… She had a handsome, loving, and high-ranking husband, Colonel Evgeny Alexandrovich Shilovsky (he was sponsored by Marshal Tukhachevsky himself). Upon learning of his wife’s secret romance with Bulgakov, Shilovsky threatened to shoot them both, swearing that in case of divorce, he would not give Elena Sergeevna their children. The lovers decided to part, and they did not see each other for long months, but their love did not weaken… And so, leaving their ten-year-old son Zhenya with his father and taking five-year-old Serezha (formally also Shilovsky’s son, but actually born from Elena Sergeevna’s past affair with Tukhachevsky), she moved in with Bulgakov. When her belongings were being loaded into the car, Shilovsky, without his cap, rushed out of the courtyard so as not to see the departure. The children’s nanny howled aloud. It was a genuine scandal, and the Moscow elite savored the details for a long time.

Elena Sergeevna lived with Mikhail Afanasyevich for eight years. There were dried roses in letters to each other. And the ball at the American ambassador’s residence in Spaso House in the columned hall, flooded with light from searchlights, with pheasants and parrots in cages, with heaps of tulips and roses. Elena Sergeevna reigned at this ball in her magnificent evening gown, dark blue with pale pink flowers. And the Master’s silk cap, sewn with her own hands, was also there…

Elena Sergeevna loved Bulgakov, knew how to empathize, was faithful, and believed that all this earned her the right to be called his only muse. As for that rejected, humiliated, and, of course, long-forgotten woman whom Bulgakov called for in the last hours of his life—well, who knows what a dying man sees in his delirium! “Misha, your wife is me now. And I am here, with you,” Elena Sergeevna persuaded him then. “And Tasya is not here. You divorced her more than fifteen years ago.” But the patient did not listen and seemed not to recognize his wife at all: “Tasya, where is she? Let Lelya (Elena, Bulgakov’s youngest sister—ed. Sovershenno Drugoy Gorod) call her. If Tasya doesn’t come, I won’t live!”

Tatyana Lappa (Tasya)

“You really won’t live?” Sasha Gdeshinsky looked at his comrade with a mixture of horror and respect.

“I won’t!” the seventeen-year-old Misha Bulgakov said firmly. “I’ll get a revolver and shoot myself to hell! You see, my soul aches endlessly. She was supposed to come for Christmas, and now, she won’t come, her parents won’t let her. And what if she never comes at all?! What if she falls in love with someone else?! I can’t bear this uncertainty any longer!”

Having hastily said goodbye to Bulgakov, Gdeshinsky rushed to the post office. And a telegram flew to Saratov: “Falsely telegraph arrival. Misha shooting himself”…

Mikhail and Tatyana

… Six months earlier, fifteen-year-old Tatyana Lappa was visiting her aunt in Kyiv and met a sixteen-year-old eighth-grade gymnasium student, Misha Bulgakov. Oh, it was no wonder Tasya’s mother did not spare the boxings on the ear (“What for, Mama?”—”Your eyes are depraved! You bore right through men with them!”—”I’m not to blame, Mama! I’ve just grown up!”)—guilty or not guilty, Tasya had bewitching eyes! Misha looked into them and was lost. Hand in hand, they wandered through the noisy Merchants’ Garden into the deserted Tsar’s Garden—to kiss. “You’re a witch, you’ve driven me mad,” Misha whispered…

… Parents intercepted their letters to each other, took away their train tickets, and locked them up… The lovers only saw each other again three years later! They stood on the vocal stage and kissed in full view of everyone. People said, “Imagine, does such love still exist in our time—unreasoning, shameless, like Romeo and Juliet?!” Well, even their parents soon had to resign themselves to Misha and Tasya’s love; and things quickly moved toward a wedding. Varvara Mikhailovna—Misha’s mother—ordered the young people to fast before the wedding. But after having a meager potato dinner with the family, the bride and groom drove to a restaurant, from there to the opera (Ruslan and Lyudmila, Aida, more often their mutual favorite, Faust), and from there to their rented room. Varvara Mikhailovna was very displeased that the young couple were living together before the wedding, but she could do nothing…

On April 25, 1913, Mikhail and Tasya were married in the Dobro-Nikolaevskaya Church in Kyiv-Podol. Bulgakov wore Tasya’s golden bracelet to the wedding—he was somehow convinced that this trinket brought good luck (he would wear the bracelet many times afterward: for his graduation exams at the university, when he was in mortal danger, when he was not paid his fee for his stories for too long, and simply when he wanted to get lucky at the casino). There were many flowers, especially daffodils. But the bride had no veil or white dress (Tasya had spent the money sent by her father for the wedding), and under the crown, she stood in a linen skirt and blouse.

Varvara Mikhailovna sighed: “Godless people! No good will come of such a marriage!”—she guessed where Tasya’s “wedding” money had gone. Medical intervention of a certain kind was dangerous and quite expensive at that time… Tasya decided on it so that no one would think she was forcing Misha to marry her.

Morphine

Both of Mikhail Bulgakov’s grandfathers were priests, and his father, Afanasy Ivanovich, although not ordained, taught at the Kyiv Theological Academy. However, when he died in 1906, it turned out that his children, yielding to the trends of the time, were almost entirely adherents of atheistic views. And the Sunday family Bible readings somehow imperceptibly gave way to literary evenings: they read Pushkin, Gogol, and Tolstoy. They played a lot of music: Vera, Nadya, Varya, and Lena played the piano beautifully, and Nikolka and Vanya played the guitar. The eldest of the children, Misha, did not study music but sang with a pleasant baritone and could quite well play Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 on the piano, for example… On odd Saturdays, they hosted jour fixes—the young people danced, sang, and philosophized.

In August 1915, the war brutally burst into the Bulgakovs’ serene life: the medical faculty course where Mikhail was studying was graduated early (the front needed doctors!). Not wanting to leave her husband, Tasya signed up as a nurse. Sixty-five years later, in an interview with literary scholar Leonid Parshin, she would recount: “There were a lot of gangrenous patients there, and Misha was constantly amputating legs. And I held those legs. I felt so sick, I thought I was going to faint. Then I’d step aside, smell some ammonia, and go back. He got so good at cutting those legs that I couldn’t keep up… I’d be holding one, and he was already sawing the other.”

A year later, Bulgakov received a new assignment: as a rural doctor in Smolensk province, Sychevsky Uyezd, Nikolske village. Misha and Tasya rejoiced: far from the front, from torn wounds and amputations… On the way from Smolensk to their destination, the joy somehow evaporated: “A repulsive impression,” Tatyana Nikolaevna recalled in the same interview. “First, terrible dirt: endless, dreary, and the view was so dreary. We arrived in the evening. There was nothing, a bare place! Some little trees…” “It’s nothing, we’ll get a good night’s sleep after the journey, everything will look cheerier in the morning,” the couple decided. But that night, as in all the subsequent ones, they failed to get proper sleep—a woman in labor was brought in. Of course, the baby was coming incorrectly, and Tasya had to search for the right passages in the Obstetrics textbook under the dim light of a lamp… Then the patients streamed in endlessly; it reached up to 100 people a day! Once, a child with diphtheria was brought to Bulgakov, and he had to use a tube to suck the membranes out of the tiny throat. Naturally, Mikhail became infected, and the anti-diphtheria serum had severe side effects: Bulgakov’s face swelled, his body was covered in a rash and itched unbearably, and he had severe pain in his legs. As an anesthetic, the young doctor begged a little morphine from the paramedic…

In a matter of days, he became a completely different person, a madman pursued by hallucinations: he kept seeing some giant snake, and this snake was suffocating him, crushing his bones. Only the white crystals could save him from the snake, and Mikhail became their slave, allowing morphine to push everything out of his heart—even his love for Tasya. Thus began their small private hell for the Bulgakov couple…

Mikhail forced his wife to go to the city for morphine. “Who is Doctor Bulgakov treating?” the pharmacists sneered at her. “Let him write the patient’s name.” If she failed to get the drug, or the solution was of a lower concentration, her husband flew into a rage. Tasya had long ago stolen his Browning pistol, but it was still scary: Bulgakov threw either the syringe or the burning kerosene lamp at her. Once, he forcibly injected Tasya with morphine (allegedly to relieve the strange pains under her stomach that had been bothering her for some time). A fear had settled in his drugged head that Tasya might betray him to his superiors, and he hoped to hedge his bets this way… Soon after this incident, she discovered she was pregnant again. In the interview with Parshin, she said that she herself did not want to give birth to a child of a morphine addict and traveled to Moscow for an abortion to Professor of Gynecology Nikolay Mikhailovich Pokrovsky (Bulgakov’s maternal uncle, who became the prototype for Professor Preobrazhensky in Heart of a Dog).

However, ten years earlier, Tatyana Nikolaevna told a completely different version (or perhaps it was simply about two different instances?). In Varlen Strongin’s book, written based on several interviews with Tatyana Nikolaevna, this episode is recounted approximately like this: Tasya was glad about her pregnancy, saying, “Misha, we will have a wonderful baby!” Her husband was silent for a while, and then said, “I will perform the operation on Thursday.” Tasya cried, pleaded, and fought. But Misha kept saying, “I am a doctor and I know what children of morphine addicts are like.” Bulgakov had never had to perform such operations before (and who would turn to a rural doctor with such a request, certainly not peasants). And before putting on the rubber gloves, he leafed through his medical reference book for a long time… The operation lasted a long time; Tasya realized something had gone wrong. “I will never have children now,” she thought dully; there were no tears, no desire to live either… When it was all over, Tasya heard the characteristic sound of an ampoule breaking, and then Misha silently lay down on the sofa and fell asleep.

What happened next has no explanation other than a mystical one. It is said that Tasya, an atheist since her gymnasium days, suddenly began to pray: “Lord, if you exist in heaven, make this nightmare end! If necessary, let Misha leave me, as long as he is cured! Lord, if you are in heaven, perform a miracle!” And a miracle happened… Having reached 16 cubes a day of a four percent morphine solution, Mikhail suddenly decided to go consult a familiar narcologist in Moscow. It was November 1917, and an uprising was raging like a fire in Moscow. Everywhere: above his head, under his feet, bullets whistled, but Bulgakov did not notice them and probably did not even realize that something terrible was happening in Russia: he was consumed by his own private catastrophe. What exactly the Moscow doctor told Mikhail Afanasyevich is unknown, but since that trip, Bulgakov began to gradually decrease his daily dose of the drug.

In 1918, they returned to Kyiv. Things there were as bad as could be: 18 coups one after another, and house No. 13 was under siege: it was unknown who would come to kill whom and under what slogan that night. Once, a whole pack of rats, maddened by hunger, broke into the house, and Mikhail and his brothers chased them with sticks. Another night, the “Blue Coats” came, wearing women’s boots for some reason, and spurs on the boots. They searched under the bed, under the table, and then said, “Let’s go from here, these are poor people, there are not even carpets.” In this chaos, morphine was sold entirely without a prescription and cost no more than bread, but Bulgakov held firm.

“Yes, Tasya, yes,” he once said, noticing his wife’s disbelievingly happy look. “The withdrawal is beginning.”

“Misha, I knew you were a strong enough person.”

Bulgakov smirked. He knew that the stage of morphinism he had reached was incurable. Something inexplicable had happened—as if some force had intervened that wanted life and some great achievements from Bulgakov, not ruin.

Guilt

In his autobiography, Bulgakov would write: “One night in 1919, in the deep autumn, riding in a rickety train, by the light of a candle inserted into a kerosene bottle, I wrote my first short story.” He began to write seriously and a lot in Vladikavkaz, while serving as a military doctor in the White Army. When the Reds entered the city and the Denikin forces fled to Turkey via Tiflis and Batumi, Bulgakov, as bad luck would have it, contracted typhus. Tasya was urged to flee, leaving her husband in the city hospital—it was believed he had no chance of survival anyway. Mikhail lost consciousness, his eyes rolled back—the doctor said, “He’s dying.” Tasya, of course, did not go anywhere and stayed with her husband almost constantly. “You are a weak woman!” Bulgakov said to her, barely having recovered. “You should have taken me out no matter what!” He still tried to fix something: he went to Batumi, held secret negotiations to hide in the hold of a ship bound for Constantinople… He told Tasya: “There’s no point in sitting here. Wherever I end up, I’ll call for you later. Go to Moscow.” Tasya left, convinced that she was parting with her husband forever. However, the escape to Turkey did not work out, and Mikhail Afanasyevich followed his wife to Moscow.

Life in Moscow went on as before: during the day, Bulgakov disappeared somewhere, always trying to get a permanent position, and at night he wrote. Tasya invariably sat nearby. His hands turned cold from nervous tension, and he asked: “Quick, hot water!” She heated water on the kerosene stove, and Bulgakov immersed his hands in a basin that was steaming… However, he only dared to read his writing to his wife once: it was Elena’s prayer, after which Nikolka recovers. Tasya, who had forgotten how she herself once whispered, “Lord, if you are in heaven…”, was surprised: “Why are you writing about this? These Turbins, they are educated people!” Bulgakov got angry: “You’re just a fool, Tasya.” In the ten-plus years since they met, nothing had changed in Tasya herself, but a lot had changed in her husband…

But there was something that remained unchanged in Bulgakov until his death—his longing for exalted, romantic, untainted love. Alas, in the relationship with Tasya, everything had become too complicated, everything intertwined: guilt, remorse, pity…. In short, Bulgakov began to cheat on his wife—frequently and quite openly. “He had tons of women,” Tatyana Nikolaevna would say in an interview. “He said he was a writer and needed inspiration, and I had to turn a blind eye to everything. So there were scandals, and once I slapped him across the face.” And then Alexei Tolstoy, who had returned from emigration, kept patting Bulgakov on the shoulder: “You have to change wives, old boy. To be a writer, you must marry three times.” “You know, let’s get a divorce,” Bulgakov finally said. “To make the necessary literary acquaintances, it’s more convenient for me to be considered single.” “So, I’ll be Lappa again?” Tasya asked, trying only not to cry. “Yes, and I’ll be Bulgakov,” his voice sounded somewhat exaggeratedly cheerful. “Don’t be angry, Tasyka, it’s very difficult in our time to remain a faithful and pure person. But I will never leave you!”

They met the New Year of 1924 at friends’ houses. They started fortune-telling: they melted wax and poured it into a bowl of water. Tasya’s outcome was something difficult to define: “A dummy,” she said. But Misha’s wax solidified in the form of two rings. Returning home, Tasya cried: “You’ll see, we’ll break up.” Bulgakov was angry: “Why do you believe in this nonsense!” At that time, he was already courting his future second wife, Lyubov Belozerskaya…

… In the autumn of that year, Mikhail Afanasyevich came home to Bolshaya Sadovaya at an unusually early hour. He drank a glass of champagne in one gulp and said: “If I can get a cart, I will move out of the house today and transport my things.” “Are you leaving me?!” Tasya asked. “Yes, I’m leaving for good. To Belozerskaya’s. Help me pack my books.” Lyubov Evgenievna Belozerskaya was acquainted with Bunin, Kuprin, Teffi, Severyanin, and Blok. Balmont, who was in love with her, once read her his poems. She had just returned from emigration and looked quite European, unlike Tasya, who had long since sold her outfits and jewelry at the flea market.

Many people disliked Lyubov Evgenievna, and they sympathized with Tasya, so Bulgakov was even refused entry to several houses after formalizing his marriage with Belozerskaya. Detractors gossiped that Mikhail Afanasyevich traded Tasya for Belozerskaya because the latter was more suitable for the role of a successful writer’s wife, which Bulgakov hoped to become after the staging of The Days of the Turbins at the Moscow Art Theatre. Friends sympathized: Mikhail could not bear the burden of his own long-standing guilt towards Tasya and wanted to break off a relationship that was too difficult to mend… But breaking up turned out to be more complicated than Bulgakov had imagined. Mikhail Afanasyevich continued to visit his ex-wife again and again. Tasya, who had neither a profession nor a trade union card, was desperately in need, and he occasionally brought her a little money—though he himself was always broke too. Once, he even asked Tasya to pawn the last remaining trinket she had—the very golden bracelet that supposedly brought him luck. “I know who needed the money,” Tasya said bitterly. “We had hard times too. But I don’t think I ever forced you to beg for other people’s things. Aren’t you ashamed, Misha?” “I am ashamed, Tassenka,” Bulgakov replied.

Tatyana Nikolaevna decided to kick her ex-husband out only when he brought her a copy of the magazine Rossiya, where his The White Guard was published. On the first page, she read: “Dedicated to Lyubov Evgenievna Belozerskaya.” Tasya hurled the magazine in Mikhail’s face: “When you wrote this novel, I was by your side. It was I who heated the water for you, I who ran to the market to sell jewelry”… Bulgakov was taken aback. Well, Belozerskaya had asked, so he added that silly dedication! Such a trifle did not seem important to him at all compared to the grandeur of the event: his novel was published!

A Dream

One day, Tasya disappeared—she moved out of her former apartment and did not appear at her friends’ places. There were rumors that she had taken a job as a laborer on a construction site. Then she left Moscow altogether for Siberia—she married a doctor there, but unfortunately, it was unsuccessful. When Bulgakov was dying, Tatyana Nikolaevna could not be found. But upon learning of his death from the newspapers, the faithful Tasya, of course, rushed to Moscow. The memorial feast was held at Bulgakov’s sister Lelya’s house. The other sisters were there too—Vera, Nadya, and Varya. But Elena Sergeevna was not invited: the Bulgakov family did not recognize any of his wives except Tasya…

Soon, Tatyana Nikolaevna was sought out by an old acquaintance—David Kiselgof. Once, during his student days in the law faculty, when he was occasionally welcomed into literary houses, he looked at Bulgakov’s wife with silent adoration, which terribly irritated the unfaithful but jealous Mikhail Afanasyevich. It turned out that David had remembered and loved Tasya for all forty years. And so, in 1965, as an elderly woman, she married for the third time and went to live in Tuapse.

In 1970, the Bulgakov scholar Marietta Chudakova miraculously tracked her down. The interview she conducted with Tatyana Nikolaevna then, and another one—taken more than ten years later by the very same literary scholar Leonid Parshin (he questioned Tasya for 15 days in a row; the phonogram amounted to 31 hours!)—filled many gaps in the great writer’s biography. However, there were still other interviews with Bulgakov’s first wife. In one of them, she recounts her dream. Allegedly, the deceased Misha came to her and said:

“My Margarita is you. Your capacity for sacrificial love was passed on to her. See, I corrected my mistake and dedicated the novel to you.”

“But there is no dedication in The Master and Margarita…”

“I couldn’t offend another woman who was by my side. But read carefully—the book is written about you…”

However, as it later turned out, some “interviewers” of Tatyana Kiselgof never even met her in reality, and now it is impossible to know what of what was written is true—on April 10, 1982, Tatyana Ivanovna died at the age of 90.