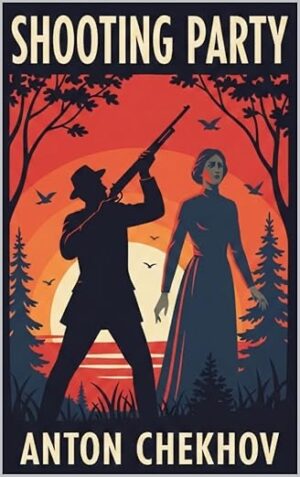

A Drama on the Hunt (The Shooting Party), Anton Chekhov: Read FREE Full Text Online (English Translation)

You can now read the full text for free of one of the most intriguing early works by the iconic author Anton Chekhov — A Drama on the Hunt (also known as The Shooting Party). This essential piece of reflective fiction Russian literature is available for online reading here in a high-quality English translation.

Dive into this captivating masterpiece and experience Chekhov’s rare foray into the sensational murder mystery genre, woven with his signature psychological depth and observation of provincial Russian society. Start reading instantly without any download required. This exclusive free access is your gateway to the world of great Russian authors and their works.

You can also buy this book from us in the definitive paperback edition via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

Drama on the Hunt (The Shooting Party) by Anton Chekhov

Page Count: 402Year: 1884READ FREEProducts search This isn’t just a detective story where the killer is known from the first page; it’s a deep psychological drama where every character wears a mask, and the truth is as elusive as a beast in the thicket. You’ll witness a tangled love triangle where jealousy, desire, and deceit intertwine with a fatal […]

€23.00 Login to Wishlist

First published in 1884 – 1885

by newspaper “Novosti Dnya”

This book is in the public domain

Reprint by Publishing House №10

Publication date July 12, 2025

Translation from Russian

216 Pages, Font 12 pt, Bookman Old Style

Electronic edition, File size 1.9 MB

Cover design, Translate by Yulia Basharova

Copyright© Yulia Basharova 2025. All rights reserved

Table of Contents

A True Incident

One April afternoon in 1880, Andrei, the doorman, entered my study and mysteriously informed me that some gentleman had appeared at the editorial office and was urgently requesting an audience with the editor.

“He must be a civil servant, sir,” Andrei added, “with a cockade…”

“Ask him to come another time,” I said. “I’m busy today. Tell him the editor only sees visitors on Saturdays.”

“He came the day before yesterday too, asking for you. Says it’s an important matter. He’s pleading, almost crying. Says he’s not free on Saturday… Shall I let him in?”

I sighed, put down my pen, and began to wait for the gentleman with the cockade. Aspiring writers, and indeed all people uninitiated into editorial secrets, who feel a sacred tremor at the word “editorial office,” tend to make you wait for quite some time. After the editor’s “show him in,” they cough for a long time, blow their noses for a long time, slowly open the door, enter even more slowly, and thus consume a good deal of time. The gentleman with the cockade, however, didn’t keep me waiting. No sooner had Andrei closed the door than I saw in my study a tall, broad-shouldered man, holding a paper parcel in one hand and a cap with a cockade in the other.

The man who had so persistently sought an audience with me plays a very prominent role in my story. It is necessary to describe his appearance.

As I’ve already said, he is tall, broad-shouldered, and stout, like a good working horse. His entire body exudes health and strength. His face is rosy, his hands large, his chest broad and muscular, his hair thick, like a healthy boy’s. He’s approaching forty. He’s dressed tastefully and in the latest fashion, in a brand-new, recently tailored tweed suit. On his chest is a large gold chain with charms, and on his little finger, a diamond ring glitters with tiny, bright stars. But most importantly, and what is so vital for any hero of a novel or story, however insignificant, he is extraordinarily handsome. I am neither a woman nor an artist. I understand little of male beauty, but the gentleman with the cockade made an impression on me with his appearance. His large, muscular face has remained forever in my memory. On this face, you will see a truly Grecian nose with a slight hump, thin lips, and fine blue eyes, in which kindness shines, and something else that is difficult to find a suitable name for. This “something” can be noticed in the eyes of small animals when they are longing or when they are in pain. Something pleading, childlike, enduring meekly… Cunning and very intelligent people do not have such eyes.

His whole face radiates simplicity, a broad, simple nature, truth… If it’s not a lie that the face is the mirror of the soul, then on the first day of my meeting with the gentleman with the cockade, I could have given my word of honor that he was incapable of lying. I could even have wagered on it.

Whether I would have lost the wager or not, the reader will see later.

His chestnut hair and beard are thick and soft as silk. They say that soft hair is a sign of a soft, gentle, “silken” soul… Criminals and evil, stubborn characters mostly have coarse hair. Whether this is true or not, the reader will again see later… Neither his facial expression nor his beard—nothing in the gentleman with the cockade is as soft and gentle as the movements of his large, heavy body. In these movements, breeding, lightness, grace, and even—forgive the expression—a certain femininity are evident. My hero would not need much effort to bend a horseshoe or flatten a sardine tin in his fist, yet none of his movements betray his physical strength. He takes hold of a doorknob or a hat as if it were a butterfly: gently, carefully, lightly touching with his fingers. His steps are silent, his handshakes weak. Looking at him, you forget that he is mighty as Goliath, that with one hand he can lift what five editorial Andreis could not. Looking at his light movements, it’s hard to believe that he is strong and heavy. Spencer might have called him a model of grace.

Entering my study, he became flustered. His delicate, sensitive nature was probably shocked by my frowning, displeased look.

“Forgive me, for God’s sake!” he began in a soft, rich baritone. “I’m bursting in on you at an inconvenient time and making you make an exception for me. You are so busy! But you see, Mr. Editor, the thing is: I’m leaving for Odessa tomorrow on a very important matter… If I had the opportunity to postpone this trip until Saturday, believe me, I wouldn’t have asked you to make an exception for me. I bow to rules, because I love order…”

“How much he talks, though!” I thought, reaching for my pen and thereby indicating that I had no time. (Visitors had become terribly tiresome to me then!)

“I’ll only take one minute of your time!” my hero continued in an apologetic voice. “But first of all, allow me to introduce myself… Bachelor of Laws Ivan Petrovich Kamyshev, former investigative magistrate… I do not have the honor of belonging to the writing fraternity, but, nevertheless, I have come to you with purely literary aims. Before you stands one who wishes to join the ranks of beginners, despite being almost forty. But better late than never.”

“Very glad… How can I be of service?”

The aspiring writer sat down and continued, looking at the floor with his pleading eyes:

“I’ve brought you a small story that I’d like to publish in your newspaper. I’ll tell you frankly, Mr. Editor: I wrote my story not for authorial fame or for sweet sounds… I’m too old for those good things. I’m embarking on the path of authorship simply for mercenary motives… I want to earn something… I currently have absolutely no occupation. I was, you see, an investigative magistrate in S— district, served for over five years, but gained neither capital nor preserved my innocence…”

Kamyshev looked up at me with his kind eyes and chuckled softly.

“A tiresome service… I served and served, then threw up my hands and quit. I have no occupation now, almost nothing to eat… And if you, overlooking its merits, publish my story, you will do me more than a favor… You will help me… A newspaper is not a charity, not a hospice… I know that, but… please, be so kind…”

“You’re lying!” I thought.

The charms and the ring on his little finger didn’t quite fit with writing for a crust of bread, and a barely noticeable cloud, perceptible only to an experienced eye, passed over Kamyshev’s face—the kind of cloud seen only on the faces of people who rarely lie.

“What’s the plot of your story?” I asked.

“The plot… How can I tell you? The plot isn’t new… Love, murder… Well, you’ll read it, you’ll see… ‘From the Notes of an Investigative Magistrate’…”

I probably winced, because Kamyshev blinked in embarrassment, fidgeted, and said quickly:

“My story is written in the style of former investigative magistrates, but… in it you will find truth, reality… Everything depicted in it, everything from cover to cover, happened before my very eyes… I was both an eyewitness and even a participant.”

“It’s not about truth… You don’t necessarily need to see something to describe it… That’s not important. The point is, our poor public has long since grown weary of Gaboriau and Shklyarevsky. They’re tired of all these mysterious murders, the cunning machinations of detectives, and the extraordinary resourcefulness of interrogating magistrates. The public, of course, varies, but I’m talking about the public that reads my newspaper. What’s your story called?”

“Drama on the Hunt.”

“Hmm… Not serious, you know… And, frankly speaking, I’ve accumulated such a mass of material that it’s absolutely impossible to accept new works, even if they have undeniable merits…”

“But please, do accept my work… You say it’s not serious, but… it’s difficult to judge a work without seeing it… And can you really not allow that investigative magistrates can also write seriously?”

Kamyshev stammered all this, twirling a pencil between his fingers and looking at his feet. He finished by becoming greatly embarrassed and blinking. I felt sorry for him.

“Alright, leave it,” I said. “Only I can’t promise you that your story will be read anytime soon. You’ll have to wait…”

“Long?”

“I don’t know… Come back in, say, two or three months…”

“Quite long… But I dare not insist… Let it be as you wish…”

Kamyshev stood up and picked up his cap.

“Thank you for the audience,” he said. “I’ll go home now and feed myself on hopes. Three months of hopes! But, I’ve probably tired you out. I have the honor to bow!”

“Just one moment,” I said, flipping through his thick notebook, filled with small handwriting. “You’re writing here in the first person… So, by ‘investigative magistrate’ here, you mean yourself?”

“Yes, but under a different surname. My role in this story is somewhat scandalous… It’s awkward to use my own name… So, in three months?”

“Yes, probably not sooner…”

“Be well!”

The former investigative magistrate bowed gallantly, carefully took hold of the doorknob, and disappeared, leaving his work on my table. I took the notebook and put it in my desk.

The handsome Kamyshev’s story rested in my desk for two months. One day, leaving the editorial office for my dacha, I remembered it and took it with me.

Sitting in the train car, I opened the notebook and began to read from the middle. The middle interested me. That same evening, despite my lack of leisure, I read the entire story from beginning to the word “The End,” written in a sprawling hand. That night, I read the story once more, and at dawn, I walked back and forth on the terrace, rubbing my temples as if I wanted to wipe away a new, suddenly appearing, tormenting thought… And the thought was indeed tormenting, unbearably sharp… It seemed to me that I, neither an investigative magistrate nor, even less so, a professional psychologist, had discovered a terrible secret about a person, a secret that was none of my business… I walked the terrace, trying to convince myself not to believe my discovery…

Kamyshev’s story did not make it into my newspaper for the reasons stated at the end of my conversation with the reader. I will meet the reader once more. For now, as I take my leave, I offer Kamyshev’s story for their reading.

This story is nothing out of the ordinary. It has many lengthy passages, quite a few rough edges… The author has a weakness for effects and strong phrases… It’s clear that he’s writing for the first time in his life, with an unaccustomed, untrained hand… But still, his story reads easily. There is a plot, and a meaning too, and, most importantly, it is original, very characteristic, and what is called sui generis (of its own kind, Latin). It also has some literary merits. It’s worth reading… Here it is.

From the Notes of an

Investigative Magistrate

Chapter I

“The husband killed his wife! Oh, how foolish you are! Give me some sugar at last!”

This shout woke me up. I stretched and felt a heaviness, a malaise, in all my limbs… One can get a limb numb, but this time it felt as if my entire body, from head to toe, was numb. An afternoon nap in a stuffy, parching atmosphere, amidst the buzzing of flies and mosquitoes, has a debilitating, not invigorating, effect. Broken and drenched in sweat, I got up and went to the window. It was six o’clock in the evening. The sun was still high and burned with the same intensity as three hours earlier. There was still a long time until sunset and coolness.

“The husband killed his wife!”

“Stop lying, Ivan Demianych!” I said, flicking Ivan Demianych’s nose lightly. “Husbands kill wives only in novels and in the tropics, where African passions boil, my dear. For us, horrors like burglaries or living under false pretenses are quite enough.”

“Burglaries…” Ivan Demianych drawled through his hooked nose. “Oh, how foolish you are!”

“But what can one do, my dear? How are we, humans, to blame that our brains have limits? However, Ivan Demianych, it’s not a sin to be a fool in such a temperature. You are clever, but I bet even your brains have turned soggy and stupid from this heat.”

My parrot is not called “Polly” or any other bird name, but Ivan Demianych. He got this name entirely by chance. One day, my servant Polikarp, while cleaning his cage, suddenly made a discovery without which my noble bird would still be called “Polly”… The lazy fellow was suddenly struck by the thought that my parrot’s nose was very similar to the nose of our village shopkeeper, Ivan Demianych, and from that moment on, the parrot was forever stuck with the name and patronymic of the long-nosed shopkeeper. With Polikarp’s light hand, the entire village christened my strange bird Ivan Demianych. By Polikarp’s will, the bird became a “person,” and the shopkeeper lost his real nickname: he would, until the end of his days, be referred to by the villagers as “the investigator’s parrot.”

I bought Ivan Demianych from the mother of my predecessor, the judicial investigator Pospelov, who had died shortly before my appointment. I bought him along with antique oak furniture, kitchen clutter, and all the household effects left by the deceased. My walls are still adorned with photographs of his relatives, and above my bed still hangs a portrait of the owner himself. The deceased, a thin, sinewy man with a reddish mustache and a large lower lip, sits, eyes bulging, in a faded walnut frame and never takes his eyes off me the entire time I lie on his bed… I haven’t removed a single photograph from the walls; in short—I left the apartment exactly as I found it. I am too lazy to bother with my own comfort, and I don’t mind not only the dead hanging on my walls, but even the living, if the latter so desire. (I beg the reader’s pardon for such expressions. Kamyshev’s unfortunate novella is rich with them, and if I did not cross them out, it was only because I deemed it necessary, in the interest of characterizing the author, to print his novella in toto (without omissions, Latin). — A. Ch.)

Ivan Demianych was as stuffy as I was. He ruffled his feathers, spread his wings, and loudly shouted phrases he had learned from my predecessor Pospelov and Polikarp. To occupy my afternoon leisure, I sat in front of the cage and observed the parrot’s movements, diligently searching for and not finding a way out of the torment caused by the stuffiness and the insects inhabiting his feathers… The poor creature seemed very unhappy…

“And at what time do they wake up?” I heard a bass voice from the anteroom…

“It varies!” Polikarp’s voice replied. “Sometimes he wakes at five, and sometimes he sleeps until morning… You know, there’s nothing to do…”

“Are you their valet?”

“A servant. Now, don’t bother me, be quiet… Can’t you see I’m reading?”

I peered into the anteroom. There, on a large red chest, lay my Polikarp, as usual, reading some book. His sleepy, never-blinking eyes fixed on the book, he moved his lips and frowned. Apparently, the presence of a stranger, a tall, bearded peasant, standing in front of the chest and vainly trying to strike up a conversation, irritated him. At my appearance, the peasant took a step back from the chest and stood at attention like a soldier. Polikarp made a displeased face and, without taking his eyes off the book, slightly raised himself.

“What do you want?” I asked the peasant.

“I’m from the Count, Your Honor. The Count sends his regards and asked you to come to him at once, sir…”

“Has the Count arrived?” I was surprised.

“Precisely so, Your Honor… Arrived last night… Here’s the letter, please…”

“The devils brought him again!” my Polikarp grumbled. “Two summers we lived peacefully without him, and now he’ll start a pigsty in the district again. There’ll be no end to the shame.”

“Be quiet, no one asked you!”

“No need to ask me… I’ll tell you myself. You’ll be coming back from him drunk and in a mess again, swimming in the lake, just as you are, in full costume… Then clean it! You won’t clean it in three days!”

“What is the Count doing now?” I asked the peasant…

“He was just sitting down to dinner when they sent me to you… Before dinner, they were fishing in the bathhouse, sir… How shall I answer?”

I opened the letter and read the following:

“My dear Lecoq! If you are still alive, well, and haven’t forgotten your most drunken friend, then, without a moment’s delay, put on your clothes and rush to me. I only arrived last night, but I am already dying of boredom. The impatience with which I await you knows no bounds. I wanted to come for you myself and take you to my den, but the heat has bound all my limbs. I sit in one place and fan myself. Well, how are you living? How is your cleverest Ivan Demianych? Still warring with your pedant Polikarp? Come quickly and tell me.

Your A. K.”

One didn’t need to look at the signature to recognize the large, ugly handwriting of my friend, Count Aleksey Korneev, rarely writing when drunk. The brevity of the letter, its attempt at playfulness and vivacity, indicated that my simple-minded friend had torn up a lot of stationery before he managed to compose this letter.

The letter lacked the pronoun “which” and carefully avoided participles — both of which the Count rarely managed in one sitting.

“How shall I answer?” the peasant repeated.

I didn’t answer that question immediately, and any fastidious person would have hesitated in my place. The Count loved me and sincerely pushed himself upon me as a friend, but I felt nothing akin to friendship for him and didn’t even like him; it would therefore have been more honest to simply refuse his friendship once and for all, rather than go to him and be hypocritical. Besides, going to the Count meant immersing myself once again in a life that my Polikarp called a “pigsty” and which, two years ago, throughout the Count’s stay before his departure for St. Petersburg, undermined my robust health and dried up my brain. This dissolute, unusual life, full of effects and drunken frenzy, did not manage to undermine my body, but it did make me known throughout the entire province… I was popular…

Reason told me the absolute truth, the blush of shame for the recent past spread across my face, my heart contracted with fear at the mere thought that I wouldn’t have the courage to refuse the trip to the Count, but I didn’t hesitate for long. The struggle lasted no more than a minute.

“Bow to the Count,” I told the messenger, “and thank him for remembering me… Tell him I’m busy and that… Tell him that I…”

And at the very moment when a decisive “no” was about to escape my tongue, a heavy feeling suddenly overwhelmed me… A young man, full of life, strength, and desires, cast by fate into a rural wilderness, was seized by a feeling of longing, of loneliness…

I remembered the Count’s garden with the luxury of its cool conservatories and the twilight of its narrow, abandoned alleys… These alleys, protected from the sun by a canopy of green, intertwining branches of old lime trees, know me… They also know the women who sought my love and the twilight… I remembered the luxurious living room, with the sweet languor of its velvet sofas, heavy curtains and carpets, soft as down, with the languor that young, healthy animals so love… My drunken daring came to mind, knowing no bounds in its breadth, satanic pride, and contempt for life. And my large body, tired from sleep, again craved movement…

“Tell him I’ll come!”

The peasant bowed and left.

“If I had known, I wouldn’t have let him in, the devil!” Polikarp grumbled, quickly and aimlessly flipping through the book.

“Leave the book and go saddle Zorka!” I said sternly. “Quickly!”

“Quickly… Indeed, without fail… So I’ll just go and run… If only it were for a real purpose, but no, he’s going to break the devil’s horns!”

This was said in a half-whisper, but loud enough for me to hear. The lackey, having whispered his impudence, stood at attention before me and, with a contemptuous smirk, awaited my angry outburst, but I pretended not to hear his words. My silence is the best and sharpest weapon in battles with Polikarp. This contemptuous disregard of his poisonous words disarms him and deprives him of ground. It acts as a punishment more effectively than a slap on the back of the head or a stream of curses… When Polikarp went out to the yard to saddle Zorka, I looked into the book I had interrupted him from reading… It was “The Count of Monte Cristo,” a terrifying novel by Dumas… My civilized fool reads everything, from pub signs to Auguste Comte, who lies in my chest with other unread, abandoned books of mine; but out of the entire mass of printed and written material, he recognizes only terrible, powerfully affecting novels with noble “gentlemen,” poisons, and underground passages; everything else he has christened “nonsense.” I will have to speak of his reading in the future, but now — to ride! A quarter of an hour later, the hooves of my Zorka were already raising dust on the road from the village to the Count’s estate. The sun was close to its rest, but the heat and stuffiness were still palpable… The heated air was motionless and dry, despite the fact that my road lay along the bank of a huge lake… To my right, I saw the mass of water, to my left, the young, spring foliage of the oak forest caressed my gaze, and meanwhile, my cheeks experienced the Sahara.

“There’s going to be a storm!” I thought, dreaming of a good, cold downpour…

The lake slept quietly. It did not greet the flight of my Zorka with a single sound, and only the squeak of a young sandpiper disturbed the deathly silence of the motionless giant. The sun looked into it as into a large mirror, and flooded its entire expanse, from my road to the distant shore, with blinding light. To my blinded eyes, it seemed that nature took its light not from the sun, but from the lake.

The heat had lulled to sleep the life with which the lake and its green banks were so rich… Birds hid, fish did not splash, field crickets and grasshoppers quietly waited for the coolness. All around was a desert. Only occasionally did my Zorka carry me into a thick cloud of coastal mosquitoes, and in the distance on the lake, three black boats of old Mikhey, our fisherman who had leased the entire lake, barely stirred.

I was riding not in a straight line, but along the circumference of the round lake. One could only travel in a straight line by boat; those traveling by land made a large circle and lost about eight versts. Throughout the journey, looking at the lake, I saw the opposite clay bank, above which a strip of flowering cherry orchard gleamed white, and from behind the cherries rose the Count’s threshing floor, dotted with multi-colored pigeons, and the small white bell tower of the Count’s church. At the clay bank stood a bathhouse, covered with sailcloth; sheets were drying on the railings. I saw all this, and it seemed to my eyes that I was separated from my friend the Count by some verst, and yet, to reach the Count’s estate, I had to gallop sixteen versts.

On the way, I thought about my strange relationship with the Count. It was interesting for me to account for them, to regulate them, but — alas! — this accounting proved to be an impossible task. No matter how much I thought and decided, in the end, I had to conclude that I was a poor connoisseur of myself and of human nature in general. People who knew me and the Count interpreted our mutual relations differently. Narrow-minded individuals, seeing nothing beyond their own noses, loved to assert that the noble Count saw in the “poor and undistinguished” judicial investigator a good hanger-on and drinking companion. I, who am writing these lines, in their understanding, crawled and groveled at the Count’s table for crumbs and scraps! In their opinion, the noble rich man, the scarecrow and envy of the entire S — district, was very intelligent and liberal; otherwise, his merciful condescension to friendship with an impoverished investigator and the genuine liberalism that made the Count insensitive to my informal “you” would be incomprehensible. Smarter people, however, explained our close relations by the commonality of “spiritual interests.” The Count and I are peers. We both graduated from the same university, we are both lawyers, and we both know very little: I know some things, while the Count has forgotten and drowned in alcohol everything he ever knew. We are both proud and, for reasons known only to us, like savages, shun society. We both disregard public opinion (i.e., of the S — district), we are both immoral, and we will both come to a bad end. Such are the “spiritual interests” that bind us. Beyond this, people who knew us could say nothing more about our relations.

They, of course, would have said more if they had known how weak, soft, and pliable was the nature of my friend the Count and how strong and firm I was. They would have said much if they had known how much this frail man loved me and how I did not love him! He was the first to offer me his friendship, and I was the first to address him informally, but with what a difference in tone! He, in a fit of good feelings, embraced me and timidly asked for my friendship — while I, once seized by a feeling of contempt, of fastidiousness, said to him:

“Stop talking nonsense!”

And he accepted this informal address as an expression of friendship and began to use it, repaying me with an honest, brotherly informal address…

Yes, I would have done better and more honestly if I had turned my Zorka around and ridden back to Polikarp and Ivan Demianych.

Later, I often thought: how many misfortunes I would not have had to bear on my shoulders, and how much good I would have brought to my neighbors, if that evening I had had the determination to turn back, if my Zorka had gone mad and carried me far away from that terrible large lake! How many tormenting memories would not now weigh on my brain and would not force my hand to constantly put down the pen and clutch my head! But I will not run ahead, especially since I will have to dwell on bitterness many more times in the future. Now, about something cheerful…

My Zorka carried me through the gates of the Count’s estate. At the very gates, she stumbled, and I, losing my stirrup, almost fell to the ground.

“A bad sign, master!” a peasant standing at one of the doors of the long Count’s stables called out to me.

I believe that a person who falls from a horse can break their neck, but I don’t believe in omens. Handing the reins to the peasant and dusting off my riding boots with my whip, I ran into the house. No one met me. The windows and doors in the rooms were wide open, but despite this, a heavy, strange smell hung in the air. It was a mixture of the smell of old, abandoned rooms with the pleasant but pungent, narcotic smell of hothouse plants recently brought from the conservatory into the rooms… In the hall, on one of the sofas upholstered in light blue silk, lay two crumpled pillows, and on a round table in front of the sofa, I saw a glass with a few drops of liquid, emitting the smell of strong Riga balm. All this indicated that the house was inhabited, but I, having walked through all eleven rooms, did not meet a single living soul. The house was as deserted as the area around the lake…

From the so-called “mosaic” living room, a large glass door led into the garden. I opened it with a noise and descended to the garden by the marble terrace. Here, after a few steps along the alley, I met the ninety-year-old old woman Nastasya, who had once been the Count’s nanny. She is a small, wrinkled creature, forgotten by death, with a bald head and prickly eyes. When you look at her face, you involuntarily recall the nickname given to her by the servants: “Sychikha”… Seeing me, she started and almost dropped a glass of cream, which she was carrying with both hands.

“Hello, Sychikha!” I said to her.

She looked at me askance and silently passed by… I took her by the shoulder…

“Don’t be afraid, you fool… Where’s the Count?”

The old woman pointed to her ears.

“Are you deaf? And how long have you been deaf?”

The old woman, despite her advanced age, hears and sees perfectly well, but finds it not superfluous to slander her senses… I threatened her with my finger and let her go.

After a few more steps, I heard voices, and a little later I saw people. In the place where the alley widened into a clearing surrounded by cast-iron benches, under the shade of tall white acacias, stood a table on which a samovar gleamed. People were talking near the table. I quietly approached the clearing across the grass and, hidden behind a lilac bush, began to search for the Count with my eyes.

Chapter II

My friend, Count Karneev, sat at the table on a folding lattice chair, drinking tea. He wore a colorful dressing gown I had seen him in two years ago, and a straw hat. His face was preoccupied, concentrated, creased, so that someone unfamiliar with him might think he was tormented by a profound thought or worry at that moment. Outwardly, the Count had not changed at all during our two-year separation. The same small, thin body, fluid and flabby, like a corncrake’s. The same narrow, consumptive shoulders with a small, reddish head. His nose was still pink, his cheeks, as two years ago, hung like rags. Nothing bold, strong, or courageous in his face… Everything was weak, apathetic, and sluggish. Only his large, drooping mustache was impressive. Someone had told my friend that long mustaches suited him. He believed it and now, every morning, measures how much longer the growth above his pale lips has become. With these mustaches, he resembled a mustachioed, but very young and frail kitten.

Next to the Count, at the same table, sat some stout man unknown to me, with a large, cropped head and very black eyebrows. His face was greasy and shiny, like a ripe melon. His mustache was longer than the Count’s, his forehead small, his lips compressed, and his eyes lazily looked at the sky… His features were blurred, yet they were hard, like dried skin. Not a Russian type… The stout man was without a frock coat or waistcoat, in just a shirt, where damp sweat stains darkened. He was drinking not tea, but seltzer water.

At a respectful distance from the table stood a plump, squat little man with a red, greasy nape and protruding ears. This was the Count’s manager, Urbénin. For His Excellency’s arrival, he had put on a new black suit and was now suffering. Sweat streamed down his red, tanned face. Next to the manager stood the peasant who had come to me with the letter. Only then did I notice that this peasant had one eye missing. Standing at attention, not allowing himself the slightest movement, he stood like a statue and awaited questions.

“I ought to take your whip, Kuzma, and give you a good thrashing,” the manager said to him slowly in his impressive, soft bass voice. “How can you execute the master’s orders so sloppily? You should have asked them to come here immediately and found out exactly when they could be here?”

“Yes, yes, yes…” the Count nervously chimed in. “You should have found out everything! He said: ‘I’ll come!’ But that’s not enough! I need him now! Absolutely now! You asked him, but he didn’t understand you!”

“What do you need him so badly for?” the stout man asked the Count.

“I need to see him!”

“Only that? Well, Aleksey, in my opinion, your investigator would do better to stay at home today. I’m not in the mood for guests right now.”

My eyes widened. What did this possessive, imperative “I” mean?

“But he’s not a guest!” my friend said in a pleading voice. “He won’t disturb your rest after the journey. Please, don’t stand on ceremony with him!… You’ll see what kind of person he is! You’ll immediately like him and become friends with him, my dear!”

I emerged from behind the lilac bushes and headed towards the table. The Count saw me, recognized me, and a smile lit up his beaming face.

“Here he is! Here he is!” he exclaimed, blushing with pleasure and springing from the table. “How kind of you!”

And running up to me, he jumped, embraced me, and with his rough mustache scratched my cheek several times. Kisses were followed by a prolonged handshake and intense looking into my eyes…

“And you, Sergei, haven’t changed a bit! Still the same! Still as handsome and strong! Thank you for honoring me and coming!”

Freeing myself from the Count’s embrace, I greeted the manager, my good acquaintance, and sat down at the table.

“Oh, my dear!” the agitated and joyful Count continued. “If only you knew how pleased I am to see your serious face! You are unfamiliar? Allow me to introduce you: my good friend Kaetan Kazimirovich Pshekhotsky. And this,” he continued, pointing me out to the stout man, “is my good, old friend Sergei Petrovich Zinoviev! The local investigator…”

The dark-browed stout man slightly rose and offered me his fat, terribly sweaty hand.

“Very pleasant,” he mumbled, examining me. “Very glad.”

Having poured out his feelings and calmed down, the Count poured me a glass of cold reddish-brown tea and pushed a box of biscuits towards me.

“Eat… I bought them at Einem’s while passing through Moscow. And I’m angry with you, Seryozha, so angry that I even wanted to quarrel with you!… Not only have you not written me a single line in these two years, but you haven’t even deigned to answer any of my letters! That’s not friendly!”

“I don’t know how to write letters,” I said, “and besides, I don’t have time for correspondence. And what, pray tell, could I have written to you about?”

“What isn’t there to write about?”

“Truly, nothing. I only recognize three types of letters: love letters, congratulatory letters, and business letters. I didn’t write the first because you are not a woman and I am not in love with you; you don’t need the second; and we are spared the third, as we have never had any common business together.”

“That, presumably, is so,” the Count agreed, quickly and readily agreeing to everything, “but still, you could have at least a line… And then, as Pyotr Egorych here says, in two years you haven’t once visited here, as if you live a thousand versts away or… despise my hospitality. You could have lived here, hunted. And who knows what might have happened here without me!”

The Count spoke at length and often. Once he started talking about something, he would rattle on incessantly and endlessly, no matter how trivial and pathetic the subject.

In uttering sounds, he was as indefatigable as my Ivan Demianych. I could barely tolerate him for this ability. This time, he was stopped by the lackey Ilya, a tall, thin man in a worn, stained livery, who presented the Count with a glass of vodka and half a glass of water on a silver tray. The Count drank the vodka, chased it with water, and, wincing, shook his head.

“So you haven’t stopped downing vodka on the go!” I said.

“Haven’t stopped, Seryozha!”

“Well, at least stop the drunken habit of wincing and shaking your head! It’s repulsive.”

“My dear, I’m giving up everything… The doctors have forbidden me to drink. I only drink now because it’s unhealthy to stop immediately… One needs to do it gradually…”

I looked at the Count’s sick, worn face, at the glass, at the lackey in yellow shoes, I looked at the dark-browed Pole, who for some reason seemed to me a scoundrel and a swindler from the very first moment, at the one-eyed peasant standing at attention — and I felt eerie, suffocated… I suddenly wanted to leave this dirty atmosphere, after first opening the Count’s eyes to my boundless antipathy towards him… There was a moment when I was ready to get up and leave… But I didn’t leave… I was prevented (I’m ashamed to admit it!) by simple physical laziness…

“Give me vodka too!” I said to Ilya.

Elongated shadows began to fall on the alley and our clearing…

The distant croaking of frogs, the cawing of crows, and the singing of an oriole already greeted the setting sun. A spring evening was descending…

“Tell Urbénin to sit down,” I whispered to the Count. “He’s standing before you like a boy.”

“Ah, I didn’t even think of it myself! Pyotr Egorych,” the Count addressed the manager, “please sit down! You needn’t stand!”

Urbénin sat down and looked at me with grateful eyes. Always healthy and cheerful, he seemed to me this time sick, bored. His face looked as if it had been crumpled, sleepy, and his eyes gazed at us lazily, reluctantly…

“What’s new, Pyotr Egorych? Anything good?” Karneev asked him. “Anything… out of the ordinary?”

“Everything’s as before, Your Excellency…”

“Anything… new girls, Pyotr Egorych?”

The moral Pyotr Egorych blushed.

“I don’t know, Your Excellency… I don’t get involved in that.”

“There are, Your Excellency,” boomed the one-eyed Kuzma, who had been silent until now. “And very worthwhile ones at that.”

“Good ones?”

“There are all kinds, Your Excellency, to suit every taste… Brunettes, blondes, all sorts…”

“Oh, really!… Wait, wait… I remember you now… My former Leporello, a secretary for… Your name is Kuzma, I believe?”

“Precisely so…”

“I remember, I remember… What ones do you have in mind now? Mostly peasant girls, I suppose?”

“Mostly peasant girls, of course, but there are some finer ones too…”

“Where did you find finer ones?” Ilya asked, squinting at Kuzma.

“The postman’s sister-in-law arrived for Holy Week… Nastas Ivanna… A girl all wound up — I’d eat her myself, but money is needed… Blood in her cheeks and all that… There’s even a finer one. She was only waiting for you, Your Excellency. Young, plump, lively… a beauty! Such beauty, Your Excellency, you haven’t even seen in Petersburg…”

“Who is that?”

“Olenka, the forester Skvortsov’s daughter.”

The chair under Urbénin creaked. Leaning his hands on the table and turning crimson, the manager slowly rose and turned his face to the one-eyed peasant. The expression of weariness and boredom gave way to strong anger…

“Shut up, boor!” he grumbled. “One-eyed snake!… Say what you want, but don’t you dare touch respectable people!”

“I’m not touching you, Pyotr Egorych,” Kuzma said impassively.

“I’m not talking about myself, idiot! However… forgive me, Your Excellency,” the manager turned to the Count. “Forgive me for making a scene, but I would ask Your Excellency to forbid your Leporello, as you were pleased to call him, from extending his zeal to persons worthy of all respect!”

“I didn’t mean anything…” the naive Count stammered. “He didn’t say anything special.”

Offended and extremely agitated, Urbénin moved away from the table and stood sideways to us. Crossing his arms over his chest and blinking, he hid his crimson face from us behind a twig and fell into thought.

Did this man not forebode that in the near future his moral sense would have to endure insults a thousand times worse?

“I don’t understand why he’s offended!” the Count whispered to me. “What an oddball! Nothing offensive was said, after all.”

After two years of sober living, the glass of vodka had a slightly intoxicating effect on me. A feeling of lightness and pleasure spread through my brain and entire body. Moreover, I began to feel the evening coolness, which gradually displaced the daytime stuffiness… I suggested a walk. The Count and his new Polish friend had their frock coats brought from the house, and we set off. Urbénin followed us.

The Count’s garden, through which we strolled, due to its striking luxury, deserves a special description. In botanical, economic, and many other respects, it is richer and grander than all the gardens I have ever seen. Besides the aforementioned poetic alleys with green arches, you will find in it everything that the eye of a capricious pampered one could demand from a garden. Here are all kinds of native and foreign fruit trees, from cherries and plums to large, goose-egg-sized apricots. Mulberries, barberries, French bergamot trees, and even olive trees are found at every step… Here are also semi-ruined, moss-grown grottoes, fountains, ponds intended for goldfish and tame carp, mountains, arbors, expensive conservatories… And this rare luxury, collected by the hands of grandfathers and fathers, this wealth of large, full roses, poetic grottoes, and endless alleys, was barbarously abandoned and surrendered to the power of weeds, the thieving axe, and jackdaws, unceremoniously building their ugly nests in rare trees! The rightful owner of this property walked beside me, and not a single muscle of his wasted and well-fed face twitched at the sight of the neglect and glaring human sloppiness, as if he were not the owner of the garden. Only once, idly, he remarked to the manager that it would not be bad if the paths were sprinkled with sand. He noted the absence of useless sand, but did not notice the bare trees that had died during the cold winter and the cows grazing in the garden. To his remark, Urbénin replied that supervising the garden would require about ten workers, and since His Excellency did not deign to live on his estate, the expenses for the garden were an unnecessary and unproductive luxury. The Count, of course, agreed with this argument.

“And I don’t have the time, I confess!” Urbénin waved his hand. “In summer, in the field, in winter, selling grain in town… No time for the garden here!”

The main, so-called “general” alley, whose entire charm lay in its old, wide lime trees and the mass of tulips stretching in two colorful strips along its entire length, ended in the distance in a yellow spot. That was a yellow stone arbor, which once housed a buffet with billiards, skittles, and a Chinese game. We aimlessly headed towards this arbor… At its entrance, we were met by a living creature that somewhat unsettled the nerves of my not-so-brave companions.

“A snake!” the Count suddenly shrieked, grabbing my arm and turning pale. “Look!”

The Pole stepped back, stood rooted to the spot, and spread his arms, as if blocking the path of a phantom… On the top step of the half-ruined stone staircase lay a young snake of the kind of our common Russian vipers. Seeing us, it raised its head and stirred… The Count shrieked again and hid behind my back.

“Don’t be afraid, Your Excellency!…” Urbénin said lazily, stepping onto the first step…

“What if it bites?”

“It won’t bite. And generally, by the way, the harm from the bite of these snakes is exaggerated. I was once bitten by an old snake — and I didn’t die, as you see.”

“A human sting is more dangerous than a snake’s!” Urbénin did not fail to moralize with a sigh.

And indeed. No sooner had the manager taken two or three steps than the snake stretched out to its full length and, with the speed of lightning, darted into a crack between two slabs. Entering the arbor, we saw another living creature. On an old, faded billiard table with torn cloth lay a short old man in a blue jacket, striped trousers, and a jockey’s cap. He was sleeping sweetly and serenely. Flies buzzed around his toothless, hollow-like mouth and on his sharp nose. Thin as a skeleton, with an open mouth and motionless, he resembled a corpse just brought from the morgue for autopsy.

“Franz!” Urbénin nudged him. “Franz!”

After five or six nudges, Franz closed his mouth, rose slightly, looked around at all of us, and lay down again. A minute later, his mouth was open again, and the flies circling his nose were again disturbed by the slight tremor of his snoring.

“Sleeping, the dissolute pig!” Urbénin sighed.

“This is our gardener Trier, I believe?” the Count asked.

“The very one… This is how it is every day… He sleeps like a log during the day, and plays cards at night. Today, they say, he played until six in the morning…”

“What does he play?”

“Gambling games… Mostly stoukolka.”

“Well, such gentlemen don’t do good work… They just take their salary for nothing.”

“I didn’t tell you that, Your Excellency,” Urbénin quickly corrected himself, “to complain or express displeasure, but simply… I just wanted to pity that such a capable man is prone to passions. And he is a hardworking man, not bad… he doesn’t take his salary for nothing.”

We glanced once more at the card player Franz and exited the arbor. From there, we headed towards the garden gate that led into the field.

In rare novels does a garden gate not play a significant role. If you haven’t noticed this yourself, then ask my Polikarp, who has devoured many terrible and not-so-terrible novels in his lifetime, and he will surely confirm this insignificant, yet characteristic fact.

My novel is also not devoid of a gate. But my gate differs from others in that my pen will have to lead many unhappy people through it and almost no happy ones, which in other novels is only the reverse. And, worst of all, I have already had to describe this gate once, but not as a novelist, but as a judicial investigator… Through it, I will see more criminals than lovers.

A quarter of an hour later, leaning on our canes, we trudged up the hill, which we call Stone Grave.

Among the villages, there is a legend that the body of some Tatar Khan rests beneath this stone pile, a Khan who feared that his enemies would desecrate his ashes after his death, and therefore bequeathed that a mountain of stone be piled upon him. But this legend is hardly true… The rock layers, their mutual superposition, and their size exclude human intervention in the origin of this mountain. It stands alone in the field and resembles an overturned cap.

Having climbed it, we saw the entire lake in all its captivating breadth and indescribable beauty. The sun was no longer reflected in it; it had set and left behind a wide crimson strip, coloring the surroundings in a pleasant, reddish-yellow hue. At our feet lay the Count’s estate with its house, church, and garden, and in the distance, on the other side of the lake, lay the grey village where, by the will of fate, I had my residence. The surface of the lake was still motionless. The old Mikhey’s boats, separated from each other, hastened towards the shore.

To the side of my village, the railway station darkened with smoke from a locomotive, and behind us, on the other side of the Stone Grave, a new scene unfolded. At the foot of the Grave ran a road, flanked by old poplars. This road led to the Count’s forest, stretching to the horizon.

The Count and I stood on the mountain. Urbénin and the Pole, being heavy men, preferred to wait for us below, on the road.

“Who’s that big shot?” I asked the Count, nodding at the Pole. “Where did you pick him up?”

“He’s a very kind gentleman, Seryozha, very kind!” the Count said worriedly. “You’ll soon become friends with him!”

“Well, that’s unlikely. Why is he always silent?”

“He’s silent by nature! But how clever he is!”

“What kind of person is he?”

“I met him in Moscow. He’s very kind. You’ll find out everything later, Seryozha, but don’t ask now. Shall we go down?”

We descended from the Grave and walked along the road towards the forest. It was noticeably getting darker. From the forest came the cuckoo’s call and the vocal tremors of a tired, probably young, nightingale.

“Hello! Hello!” we heard a clear child’s voice as we approached the forest. “Catch me!”

And out of the forest ran a little girl, about five years old, with hair as white as flax and in a blue dress. Seeing us, she burst into clear laughter and, skipping, ran up to Urbénin and hugged his knee. Urbénin picked her up and kissed her cheek.

“My daughter Sasha!” he said. “I recommend.”

Following Sasha from the forest was a fifteen-year-old gymnasium student, Urbénin’s son. Seeing us, he indecisively took off his cap, put it on, and took it off again. Behind him, a red spot moved quietly. This spot immediately drew our attention.

“What a wondrous vision!” exclaimed the Count, grabbing my arm. “Look! What a delight! Who is that girl? I didn’t know such naiads inhabited my forests!”

I looked at Urbénin to ask who this girl was, and, strangely, only at that moment did I notice that the manager was terribly drunk. Red as a lobster, he swayed and grabbed my elbow.

“Sergei Petrovich!” he whispered in my ear, breathing alcoholic fumes on me, “I implore you — restrain the Count from further remarks about this girl. He might say something unnecessary out of habit, and she is an extremely respectable person!”

The “extremely respectable person” was a nineteen-year-old girl with a beautiful blonde head, kind blue eyes, and long curls. She was in a bright red, half-childish, half-maidenly dress. Her slender, needle-like legs in red stockings were encased in tiny, almost childish shoes. Her rounded shoulders constantly shrugged coquettishly while I admired her, as if they were cold and as if my gaze was biting them.

“Such a young face and such developed forms!” the Count whispered to me, who had lost the ability to respect women and not look at them from the perspective of a debauched animal in his early youth.

As for me, I remember a good feeling igniting in my chest. I was still a poet, and in the company of forests, a May evening, and the beginning of a twinkling evening star, I could only look at a woman as a poet… I looked at the girl in red with the same reverence with which I was accustomed to looking at forests, mountains, and the azure sky. I still had some sentimentality then, inherited from my German mother.

“Who is this?” the Count asked.

“This is the forester Skvortsov’s daughter, Your Excellency!” Urbénin said.

“Is this the Olenka the one-eyed peasant was talking about?”

“Yes, he mentioned her name,” the manager replied, looking at me with pleading, wide eyes.

The girl in red walked past us, seemingly paying us no attention. Her eyes looked somewhere to the side, but I, a man who knows women, felt her pupils on my face.

“Which of them is the Count?” I heard her whisper behind us.

“This one, with the long mustache,” the gymnasium student replied.

And we heard silvery laughter behind us… It was the laughter of someone disappointed… She thought that the Count, the owner of these huge forests and the wide lake — was me, not this pygmy with a wasted face and long mustache…

I heard a deep sigh escaping Urbénin’s sturdy chest. The iron man barely moved.

“Let the manager go,” I whispered to the Count. “He’s sick or… drunk.”

“You seem to be unwell, Pyotr Egorych!” the Count addressed Urbénin. “I don’t need you, so I won’t detain you.”

“Don’t worry, Your Excellency. Thank you for your attention, but I am not ill.”

I looked back… The red spot didn’t move and watched us go…

Poor blonde head! Did I, on this quiet, peaceful May evening, ever imagine that she would later become the heroine of my restless novel?

Now, as I write these lines, the autumn rain angrily taps on my warm windows, and somewhere above me the wind howls. I look at the dark window and, against the backdrop of the night’s gloom, I try to create my dear heroine by force of imagination…

And I see her with her innocently childlike, naive, kind face and loving eyes. I want to throw down my pen and tear up, burn what has already been written. Why touch the memory of this young, innocent creature?

But right here, next to my inkwell, stands her photographic portrait. Here, the blonde head is presented in all the vain grandeur of a deeply fallen beautiful woman. Her eyes, tired but proud of their depravity, are motionless. Here she is precisely the snake whose bite Urbénin would not have called exaggerated.

She gave the storm a kiss, and the storm broke the flower at its very root. Much was taken, but too dearly paid for. The reader will forgive her sins…

We walked through the forest.

Pine trees are boring in their silent monotony. All are of the same height, resemble one another, and retain their appearance in all seasons, knowing neither death nor spring renewal. But they are attractive in their gloominess: motionless, silent, as if lost in mournful thought.

“Shall we go back?” the Count suggested.

This question went unanswered. The Pole was utterly indifferent as to where he was, Urbénin did not consider his voice decisive, and I was too delighted by the forest’s coolness and resinous air to turn back. Besides, we needed to kill time until nightfall, even if it was just with a simple walk. The thought of the approaching wild night was accompanied by a sweet fluttering in my heart. I, ashamed to admit it, dreamed of it and mentally already savored its pleasure. And from the impatience with which the Count kept glancing at his watch, it was clear that he, too, was tormented by anticipation. We felt that we understood each other.

Near the forester’s house, nestled among the pines in a small square clearing, two small yellow-fire-colored dogs of an unknown breed, flexible as eels and sleek, met us with a loud, melodious bark. Recognizing Urbénin, they wagged their tails cheerfully and ran to him, from which one could conclude that the manager often visited the forester’s house. Right there, near the house, we were met by a young fellow without boots or a cap, with large freckles on his surprised face. For a moment, he looked at us silently, wide-eyed, then, probably recognizing the Count, gasped and ran headlong into the house.

“I know why he ran,” the Count laughed. “I remember him… That’s Mitka.”

The Count was not mistaken. In less than a minute, Mitka emerged from the house, carrying a glass of vodka and half a glass of water on a tray.

“To your good health, Your Excellency!” he said, offering it and smiling with his entire foolish, surprised face.

The Count drank the vodka, “chased” it with water, but this time did not wince. A hundred steps from the house stood a cast-iron bench, as old as the pines. We sat on it and began to contemplate the May evening in all its quiet beauty… Above our heads, startled crows flew, cawing, and nightingale songs came from various directions; this alone disturbed the general silence.

The Count cannot keep silent even on a quiet spring evening, when the human voice is least pleasant.

“I don’t know if you’ll be satisfied?” he turned to me. “I ordered perch soup and game for dinner. For vodka, there will be cold sturgeon and suckling pig with horseradish.”

As if angered by this prose, the poetic pines suddenly stirred their tops, and a quiet murmur passed through the forest. A fresh breeze ran through the clearing and played with the grass.

“That’s enough!” Urbénin shouted at the fiery-colored little dogs, who were hindering him with their affection as he tried to light a cigarette. “And it seems to me that it will rain today. I feel it in the air. Today was such terrible heat that you don’t need to be a learned professor to predict rain. It will be good for the grain.”

“And what good is grain to you,” I thought, “if the Count drinks it all away? No need for the rain to even bother.”

The breeze rustled through the forest once more, but this time it was sharper. The pines and grass murmured louder.

“Let’s go home.”

We stood up and lazily shuffled back towards the house.

“It’s better to be this blonde Olenka,” I said to Urbénin, “and live here with the beasts, than to be a judicial investigator and live with people… It’s more peaceful. Isn’t that right, Pyotr Egorych?”

“Whatever you are, as long as your soul is at peace, Sergei Petrovich.”

“And is this pretty Olenka’s soul at peace?”

“Only God knows another’s soul, but it seems to me she has nothing to worry about. Not much grief, as few sins as a child… She is a very good girl! But now, at last, the sky has spoken of rain…”

A rumble was heard, whether of a distant carriage or a game of skittles… Thunder rumbled somewhere in the distance beyond the forest… Mitka, who had been watching us all along, flinched and quickly crossed himself…

“A thunderstorm!” the Count started. “What a surprise! It’ll catch us on the road… And it’s gotten so dark! I said: ‘Let’s go back!’ But no, you kept going…”

“We’ll wait out the storm in the house,” I suggested.

“Why in the house?” Urbénin said, blinking strangely. “The rain will fall all night, so will you sit in the house all night? And don’t you bother yourself… Go on, and Mitka will run ahead, he’ll send a carriage to meet you.”

“It’s nothing, maybe the rain won’t lash all night… Thunderstorm clouds usually pass quickly… Besides, I’m not yet acquainted with the new forester, and I’d like to chat with this Olenka… to find out what kind of bird she is…”

“I’m not against it!” the Count agreed.

“But how will you go there, if… if it’s… not tidy?” Urbénin stammered anxiously. “To sit there in the stuffiness, Your Excellency, when you could be at home… I don’t understand what pleasure!… And to get acquainted with the forester, if he’s ill…”

It was clear that the manager strongly disliked the idea of us entering the forester’s house. He even spread his arms, as if to block our way… I understood from his face that he had reasons not to let us in. I respect other people’s reasons and secrets, but this time, curiosity strongly spurred me on. I insisted, and we entered the house.

“Come into the hall!” the barefoot Mitka said, or rather, somehow particularly hiccupped, choking with joy…

Imagine the smallest hall in the world, with unpainted wooden walls. The walls were hung with oleographs from “Niva,” photographs in shell-decorated, or as we call them, “seashell” frames, and certificates… One certificate was a thank-you from some baron for long service, the rest were horse-related… Ivy climbed here and there along the walls… In the corner, before a small icon, a blue flame quietly flickered and faintly reflected in a silver setting. Chairs huddled against the walls, apparently recently purchased… Many extra ones were bought, but they were all put out: there was nowhere else to put them… Here, too, crowded armchairs with a sofa in snow-white covers with ruffles and lace, and a round lacquered table. On the sofa, a tame rabbit dozed… Cozy, clean, and warm… The presence of a woman was noticeable everywhere. Even the small bookcase with books looked somehow innocent, feminine, as if it wanted to say that it contained nothing but weak novels and meek poems… The charm of such cozy, warm rooms is felt less in spring than in autumn, when one seeks shelter from the cold and dampness…

Mitka, with a loud huff and puff, fiercely striking matches, lit two candles and carefully, like milk, placed them on the table. We sat in the armchairs, exchanged glances, and laughed…

“Nikolai Efimych is sick in bed,” Urbénin explained the absence of the hosts, “and Olga Nikolaevna must have gone to see my children off…”

“Mitka, are the doors locked?” we heard a faint tenor voice from the next room.

“Locked, sir, Nikolai Efimych!” Mitka croaked and flew headlong into the next room.

“Good… Make sure they’re all locked… tightly…” said the same weak voice. “With the key, very tightly… If thieves try to get in, you’ll tell me… I’ll shoot them, those villains… those scoundrels…”

“Certainly, sir, Nikolai Efimych!”

We laughed and looked inquiringly at Urbénin. He blushed and, to hide his embarrassment, began to adjust the curtain on the window… What did this dream mean? We exchanged glances again.

But there was no time to ponder. Hurried footsteps were heard in the yard, then a noise on the porch and a door slamming. The girl in red flew into the “hall.”

“I love a thunderstorm in early May!” she sang in a high, squealing soprano, interrupting her squeals with laughter, but seeing us, she suddenly stopped and fell silent.

She was embarrassed and quietly, like a lamb, went into the room from which her father’s voice, Nikolai Efimych, had just been heard.

“Didn’t expect that!” Urbénin chuckled.

After a while, she quietly re-entered, sat on the chair nearest the door, and began to observe us. She looked at us boldly, directly, as if we were not new people to her, but animals in a zoological garden. For a minute, we also looked at her silently, without moving… I would have agreed to sit motionless for a year and look at her — that’s how beautiful she was that evening. Fresh as air blush, frequently breathing, rising chest, curls scattered over her forehead, shoulders, and right hand adjusting her collar, large shining eyes… all this on one small body, absorbed in one glance… You look at this small space once and see more than if you had looked for entire centuries at the endless horizon… She looked at me seriously, from below upwards, inquiringly; but when her eyes moved from me to the Count or the Pole, I began to read the opposite in them: a glance from above downwards and laughter…

I was the first to speak.

“Allow me to introduce myself,” I said, standing up and approaching her, “Zinoviev… And this, I recommend, is my friend, Count Karneev… We apologize for breaking into your pretty little house without an invitation… We, of course, would not have done this if the thunderstorm hadn’t driven us in…”

“But our little house won’t fall apart because of that!” she said, laughing and offering me her hand.

She showed me lovely teeth. I sat next to her on a chair and told her how unexpectedly the thunderstorm had met us on our path. A conversation about the weather began — the beginning of all beginnings. While we talked, Mitka had already managed to bring the Count vodka twice, and the inseparable water… Taking advantage of my not looking at him, the Count, after both glasses, winced sweetly and shook his head.

“Perhaps you’d like something to eat?” Olenka asked me and, without waiting for an answer, left the room…

The first drops tapped on the windowpanes… I went to the window… It was already completely dark, and through the glass, I saw nothing but raindrops crawling down and the reflection of my own nose. A flash of lightning gleamed and illuminated several nearby pines…

“Are the doors locked?” I heard the weak tenor voice again. “Mitka, go, you vile soul, lock the doors! My torment, Lord!”

A woman with a double, cinched stomach and a foolish, preoccupied face entered the hall, bowed low to the Count, and covered the table with a white tablecloth. Behind her, Mitka moved cautiously, carrying snacks. A minute later, vodka, rum, cheese, and a plate with some fried bird stood on the table. The Count drank a glass of vodka but did not eat. The Pole sniffed the bird distrustfully and began to cut it.

“The rain has already started! Look!” I said to Olenka as she entered.

The girl in red approached my window, and at that very moment, we were illuminated for an instant by a white glow… A crackling sound echoed above, and it seemed to me that something large and heavy had torn loose from its place in the sky and was rolling down to earth with a thunderous roar… The windowpanes and the glasses before the Count shuddered and emitted their glassy sound… The impact was strong…

“Are you afraid of thunderstorms?” I asked Olenka.

She pressed her cheek to her rounded shoulder and looked at me with childlike trust.

“I’m afraid,” she whispered, after a moment’s thought. “A thunderstorm killed my mother… They even wrote about it in the newspapers… My mother was walking across a field and crying… She had a very bitter life in this world… God took pity on her and killed her with His heavenly electricity.”

“How do you know it was electricity?”

“I studied… Do you know? Those killed by lightning, and in war, and those who die in difficult childbirth go to heaven… It’s not written anywhere in books, but it’s true. My mother is in heaven now. I think a thunderstorm will kill me someday too, and I will also be in heaven… Are you an educated person?”

“Yes…”

“Then you won’t laugh… This is how I would like to die. To put on the most expensive, fashionable dress, like the one I saw the other day on the rich lady here, the landowner Sheffer, to wear bracelets on my arms… Then to stand on the very top of Stone Grave and let lightning kill me so that all people would see… A terrible thunder, you know, and the end…”

“What a wild fantasy!” I chuckled, looking into her eyes, full of sacred terror before a terrible, but spectacular death. “And in an ordinary dress, you don’t want to die?”

“No…” Olenka shook her head. “And so that all people would see.”

“Your current dress is better than any fashionable and expensive dresses… It suits you. In it, you look like a red flower of the green forest.”

“No, that’s not true!” Olenka sighed naively. “This dress is cheap, it can’t be good.”

The Count approached our window with the clear intention of speaking with the pretty Olenka. My friend speaks three European languages, but does not know how to speak to women. He stood awkwardly near us, smiled foolishly, grunted “hmm,” and retreated to the decanter of vodka.

“When you came into this room,” I said to Olenka, “you sang ‘I love a thunderstorm in early May.’ Are those verses set to music?”

“No, I sing all the poems I know in my own way.”

I happened to glance back. Urbénin was looking at us. In his eyes, I read hatred and malice, which did not at all suit his kind, soft face.

“Is he jealous, or something?” I thought.

The poor fellow, catching my questioning glance, rose from his chair and went into the anteroom for some reason… Even by his gait, it was noticeable that he was agitated. The claps of thunder, each stronger and more rolling than the last, began to repeat more and more frequently… Lightning continuously painted the sky, the pines, and the wet ground in its pleasant, dazzling light… The rain was still far from over. I moved from the window to the bookcase and began to examine Olenka’s library. “Tell me what you read, and I will tell you who you are,” but from the goods symmetrically resting on the bookcase, it was difficult to draw any conclusion about Olenka’s intellectual level or “educational qualification.” There was a strange mixture here. Three anthologies, one book by Born, Evtushevsky’s problem book, the second volume of Lermontov, Shklyarevsky, the journal “Delo,” a cookbook, “Skladchina”… I could have listed even more books for you, but at the moment when I took “Skladchina” from the bookcase and began to leaf through it, the door from another room opened, and a subject entered the hall who immediately diverted my attention from Olenka’s educational qualification. This was a tall, sinewy man in a calico dressing gown and torn slippers, with a rather original face. His face, etched with blue veins, was adorned with sergeant-major’s mustaches and sideburns, and in general resembled a bird’s physiognomy. His entire face was stretched forward, as if striving towards the tip of his nose… Such faces are called, I believe, “jug-snouts.” This subject’s small head sat on a long, thin neck with a large Adam’s apple and swayed like a starling’s nest in the wind… The strange man surveyed us with murky, green eyes and stared at the Count…

“Are the doors locked?” he asked in a pleading voice.

The Count looked at me and shrugged…

“Don’t worry, Papa!” Olenka said. “Everything’s locked… Go to your room!”

“And is the shed locked?”

“He’s a little… touched sometimes,” Urbénin whispered, appearing from the anteroom. “He’s afraid of thieves and, as you can see, he’s always fussing about the doors… Nikolai Efimych,” he addressed the strange subject, “go to your room and go to sleep! Don’t worry, everything is locked!”

“And are the windows locked?”

Nikolai Efimych quickly ran around all the windows, tried their latches, and without looking at us, shuffled in his slippers to his room.

“It comes over him sometimes, the poor fellow,” Urbénin began to explain after his departure. “A good, glorious man, you know, a family man — and such an affliction! He gets confused almost every summer…”

I looked at Olenka. She blushingly, hiding her face from us, straightened her disturbed books. She seemed ashamed of her mad father.

“And the carriage has arrived, Your Excellency!” Urbénin said. “You can leave if you wish!”

“Where did this carriage come from?” I asked.

“I sent for it…”

A minute later, the Count and I were sitting in the carriage, listening to the rumbling of thunder, and I was angry…

“That Pyotr Egorych, damn him, really drove us out of the house!” I grumbled, genuinely annoyed. “He didn’t even let me get a good look at that Olenka! I wouldn’t have eaten her, for heaven’s sake… The old fool! He was bursting with jealousy the whole time… He’s in love with that girl…”

“Yes, yes, yes… Imagine, I noticed that too! And he didn’t let us into the house only out of jealousy, and he sent for the carriage out of jealousy… Haha!”

“Old age in the beard, and the devil in the ribs… However, brother, it’s hard not to fall in love with that girl in red, seeing her every day as we saw her today! Devilishly pretty! Only she’s not for his snout… He should understand that and not be so selfishly jealous… Love, but don’t hinder others, especially when you know she’s not meant for you… What an old blockhead!”

“Remember how he flared up when Kuzma mentioned her name at tea?” the Count giggled. “I thought he’d beat us all then… People don’t defend the honor of a woman they’re indifferent to so passionately…”

“They do, brother… But that’s not the point… The important thing is this… If he commanded us so much today, then what does he do to the small people, those who are under his command! I bet he doesn’t let the keymasters, stewards, hunters, and other lowly folk even approach her! Love and jealousy make a person unfair, heartless, a misanthrope… I bet he’s already eaten up more than one employee under his command because of this Olenka. So you’ll do wisely if you trust his complaints about employees and reports about the necessity of expelling one or another less. In general, limit his power for a while… Love will pass — well, then there will be nothing to fear. He is a kind and honest fellow…”

“And how do you like her father?” the Count laughed.

“Mad… He should be in a lunatic asylum, not managing forests… In general, you wouldn’t be lying if you hung a sign on your estate gates: ‘Lunatic Asylum’… You have a real Bedlam here! This forester, Sychikha, Franz, obsessed with cards, the old man in love, the exalted girl, the drunken Count… what could be better?”

“But this forester gets a salary! How does he serve if he’s mad?”

“Obviously, Urbénin keeps him only because of his daughter… Urbénin says that Nikolai Efimych gets this way almost every summer… But that’s hardly true… This forester is not just ill every summer, he’s constantly ill… Fortunately, your Pyotr Egorych rarely lies and gives himself away if he does tell a fib…”

“Last year Urbénin notified me that the old forester Akhmetiev was going to become a monk on Mount Athos, and recommended the ‘experienced, honest, and deserving’ Skvortsov… I, of course, consented, as I always do. Letters are not people: they don’t give themselves away if they lie.”

The carriage entered the courtyard and stopped at the entrance. We got out. The rain had already passed. The thundercloud, flashing lightning and emitting an angry rumble, hastened northeast, revealing more and more of the blue, starry sky. It seemed a heavily armed force, having wrought devastation and taken a terrible toll, rushed to new victories… The lagging clouds chased after it and hurried, as if afraid of not catching up… Nature regained its peace…

And this peace was felt in the quiet, fragrant air, full of languor and nightingale melodies, in the silence of the sleeping garden, in the caressing light of the rising moon… The lake awoke from its daytime slumber and with a gentle grumble made its presence known to human ears…

At such a time, it is good to ride through the field in a comfortable carriage or work the oars on the lake… But we went into the house… There, another kind of “poetry” awaited us.

Chapter III

A suicide is one who, under the influence of mental pain or oppressed by unbearable suffering, puts a bullet through their head; but for those who give rein to their pitiful, soul-debasing passions in the sacred days of spring and youth, there is no name in human language. After the bullet comes the peace of the grave; after ruined youth come years of sorrow and tormenting memories. He who has profaned his spring understands the current state of my soul. I am not yet old, not gray, but I am no longer living. Psychiatrists say that a soldier, wounded at Waterloo, went mad and afterwards assured everyone, and believed it himself, that he was killed at Waterloo, and that what they now consider him to be is only his shadow, a reflection of the past. Something similar to this half-death I am now experiencing…

“I am very glad you didn’t eat anything at the forester’s and didn’t spoil your appetite,” the Count told me as we entered the house. “We’ll have an excellent dinner… just like old times… Serve!” he commanded Ilya, who was pulling off his frock coat and putting on his dressing gown.

We went to the dining room. Here, on the set table, “life was already boiling.” Bottles of all colors and sizes stood in rows, like on shelves in theater buffets, and, reflecting the lamp light, awaited our attention. Salted, pickled, and all other appetizers stood on another table with a decanter of vodka and English bitters. Next to the wine bottles stood two dishes: one with a suckling pig, the other with cold sturgeon…

“Well then…” the Count began, pouring three glasses and shivering as if from the cold. “To our health! Take your glass, Kaetan Kazimirovich!”

I drank; the Pole, however, shook his head negatively. He pulled the sturgeon towards him, sniffed it, and began to eat.

I ask the reader’s forgiveness. Now I will have to describe something entirely un-“romantic.”

“Well then… they had another,” the Count said, pouring second glasses. “Go for it, Lecocq!”

I took my glass, looked at it, and put it down…

“Damn it, I haven’t had a drink in ages,” I said. “Shall we recall old times?” And without a second thought, I poured five glasses and downed them one after another. I didn’t know how to drink otherwise. Small schoolchildren learn to smoke cigarettes from older ones: the Count, watching me, poured himself five glasses and, bending into an arch, wincing and shaking his head, drank them. My five glasses seemed like bravado to him, but I was not drinking to boast of my drinking talent… I wanted intoxication, a good, strong intoxication, one I hadn’t felt in a long time, living in my village. Having drunk, I sat down at the table and began on the suckling pig…

Intoxication didn’t keep me waiting long. Soon I felt a slight dizziness. A pleasant chill played in my chest — the beginning of a happy, expansive state. Suddenly, without any noticeable transition, I became terribly cheerful. The feeling of emptiness and boredom gave way to a sensation of complete mirth and joy. I began to smile. I suddenly craved chatter, laughter, people. Chewing the suckling pig, I began to feel the fullness of life, almost the very contentment with life, almost happiness.

“Why aren’t you drinking anything?” I asked the Pole.

“He doesn’t drink anything,” the Count said. “Don’t force him.”

“But still, you must drink something!”

The Pole put a large piece of sturgeon in his mouth and shook his head negatively. His silence egged me on.

“Listen, Kaetan… what’s your patronymic… why are you always silent?” I asked him. “I haven’t yet had the pleasure of hearing your voice.”

His two eyebrows, like a flying swallow, rose, and he looked at me.

“Do you wish me to speak?” he asked with a strong Polish accent.

“Very much so.”

“And why?”

“Pardon me! On steamboats at dinner, strangers and unfamiliar people strike up conversation, and we’ve known each other for several hours, looking at each other, and haven’t exchanged a single word! What kind of behavior is that?”

The Pole remained silent.