9 Quotes from Elena Bulgakova’s Diary

Elena Sergeevna Bulgakova, née Nyurenberg, kept a diary from 1933 to 1970. Her entries from the 1930s recount the writer’s daily life, his relationships with contemporaries, his work on texts, and new ideas.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

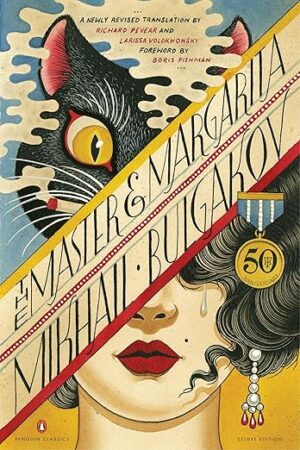

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

Page Count: 448Year: 1967Products search Imagine 1930s Moscow — a city constrained by bureaucracy, shortages, and state-enforced atheism — is suddenly visited by Satan himself, in the guise of Professor Woland, accompanied by his infernal retinue, including the absurdly dressed Koroviev and the massive, talking cat Behemoth. Woland’s visit is a devilish inspection and a session of black […]

€11.00 Login to Wishlist

1. On the Search

“<…> Misha insists that I keep this diary. He himself, after his diaries were confiscated during a search in 1926, vowed never to keep a diary. The thought that a writer’s diary could be seized is terrible and incomprehensible to him.” September 1, 1933

In May 1926, OGPU agents seized Bulgakov’s diary, returning it only at the end of 1929 (after machine-typed and photographic copies had been made of the manuscript). The writer destroyed the text and never kept a diary again, asking his wife to make entries instead of him.

2. On Quirks

“<…> For M.A., ‘apartment’ is a magic word. He doesn’t envy anything in the world—except a good apartment! It’s some kind of quirk with him.” August 23, 1934

Bulgakov’s characters are often intellectuals who have lost their homes and found themselves in the atmosphere of a communal apartment. Like he did himself. From the early 1920s, the writer lived in communal apartments, and only in 1927 was he able to rent a separate apartment in house 35A on Bolshaya Pirogovskaya Street in Moscow. Even separate apartments, alas, had their drawbacks: the one on Pirogovskaya was damp, and the one on Furmanov Street suffered from monstrous audibility that hindered work.

3. On Nerves and Hypnosis

“M.A. is having trouble with his nerves. Fear of space, of loneliness. He is thinking about whether to seek hypnosis.” October 13, 1934

Soviet medicine often used hypnotic suggestion, which was common before the revolution. In entries made from October 1934 to February 1935, Elena Sergeevna mentions Semyon Mironovich Berg several times, who treated the writer using hypnosis. The writer, who suffered from a “severe form of neurasthenia” by his own definition, thanked the specialist on April 30, 1935: “In short, I feel very well. You have made it so that the cursed fear does not torment me. It is far and muffled.”

4. On the Christmas Tree and Home Performances

“There was a Christmas tree. First, M.A. and I decorated the tree, laid out gifts for everyone under it. Then we turned off the electric light, lit the candles on the tree, M.A. played a march—and the children rushed into the room. Then—according to the program—a performance. M.A. wrote two scenes (based on Dead Souls). One—at Sobakevich’s. The other—at Sergei Shilovsky’s. Chichikov—I. Sobakevich—M.A. Then—Zhenichka—I, Sergei—M.A. M.A. did my makeup with a cork, lipstick, and powder. The curtain—a blanket on the door from the study to the middle room. The stage—in the study. For the role of Sergei, M.A. put on shorts, Sergei’s coat over them, which barely reached his waist, and a sailor cap on his head. He smeared his mouth with lipstick. <…> A success. Then a Christmas dinner—pelmeni and a mass of sweets.” December 24, 1934

Throughout his life, since childhood, Bulgakov participated in home performances. His sister Nadezhda Zemskaya recalled: “<…> In our house, music and singing were constantly playing and—laughter, laughter, laughter. We danced a lot. We put on charades and plays. Mikhail Afanasyevich was the director of the charade productions and shone as an actor in charades and amateur plays.”

5. On Stanislavsky and His System

“M.A. comes back exhausted from rehearsals at K.S.’s. K.S. is doing pedagogical études with the actors. M.A. is furious—there is no system and there cannot be. You cannot force a bad actor to act well. Then he entertains himself and me by showing how Koreneva plays Madeleine. He puts on my nightgown, kneels, and hits his forehead on the floor (the scene in the cathedral).” April 7, 1935

While Bulgakov had good relations with Stanislavsky, who headed the Moscow Art Theatre (MXAT) when The Days of the Turbins was staged in the 1920s, their relationship cooled significantly after more than four years of rehearsals for the play Molière. In April 1935, Bulgakov was unpleasantly surprised that Stanislavsky “intends to completely break and re-write the whole play,” and three years later called his famous system shamanism. In an entry made in November 1938, Elena Sergeevna quotes the writer: “Stanislavsky’s system is shamanism. Take Ershov, for example. A charming person, but an actor you couldn’t imagine worse. And all—according to the system. <…> But Tarkhanov, without any of Stanislavsky’s system—is the most brilliant actor!”

6. On Jokes and Chess

“<…> Dmitriev came in the evening. M.A. mystified him, said that he was a second-class chess player, and offered Dmitriev a handicap. Dmitriev turned pale with every move, although he plays excellently. Of course, he completely beat M.A., but he smoked a pack of cigarettes out of agitation. When M.A. confessed to him—he laughed wildly.” September 12, 1935

Bulgakov played chess quite often. His opponents included the literary critic Nikolay Lyamin, the theatre designer Sergey Topleninov, the playwright Sergey Ermolinsky, and the surgeon Andrey Arendt. The writer also taught his stepson to play chess: “<…> Misha taught him to play, and when Sergei won (you understand, this was necessary for pedagogical purposes), Misha wrote me a note: ‘Give Sergei half a bar of chocolate. Signature.'”

7. On Money

“Today a competition for a textbook on the history of the USSR was announced in the newspaper. M.A. said that he wants to write a textbook—he needs to prepare materials, textbooks, and atlases.” March 4, 1936

The spring of 1936 was difficult: performances of Molière were stopped at MXAT after a few showings, the comedy Ivan Vasilievich was banned at the Satire Theatre after the dress rehearsal, and work on the play Alexander Pushkin was suspended at the Vakhtangov Theatre. During this time, Bulgakov worked on a history textbook of the USSR. The newspaper announcement for the competition offered four prizes: 25,000, 50,000, 75,000, and 100,000 rubles. The last figure is circled in red pencil (coincidentally, this is exactly how much the Master wins in the lottery).

8. On Tonsillitis and Scarlet Fever

“Sergey fell ill. Shapiro says—tonsillitis.” December 13, 1936

“At night, M.A. determined that it was not tonsillitis but scarlet fever. Shapiro, who arrived at seven in the morning, confirmed M.A.’s diagnosis.” December 15, 1936

Despite ceasing his medical practice in the early 1920s, Bulgakov did not lose his professional skills and maintained an interest in medicine. Sergey Ermolinsky recalled that Bulgakov’s demeanor would change when he returned to the art of healing: “…strict, concerned, with a small suitcase in his hands, from which he took out a spirit lamp, a thermometer, and cupping glasses. Then he would seat me, turn my back, tap with a bent finger, make me open my mouth and say ‘ah’…” Bulgakov used to tell his patient that “the nastiest disease is the kidneys. It creeps up like a thief.”

9. On Death

“<…> …we met the New Year: Ermolinsky—with a glass of vodka in his hands, Sergey and I—with white wine, and Misha—with a measuring cup of medicine. We made a dummy of Misha’s illness—with a fox head (from my black fox fur), and Sergey, by lot, shot it.” January 1, 1940

In a letter to Nikolay Bulgakov, the writer’s brother, dated January 5, 1961, Elena Sergeevna recounted that in the 1930s, Mikhail Afanasyevich shared a premonition with her several times that he would have a difficult death, although X-rays and tests showed normal results. In September 1939, doctors discovered nephrosclerosis in Bulgakov. Fate allotted the writer six months of life—during this time, he made corrections to the novel The Master and Margarita and also tried to make sketches for new works. On March 10, 1940, Elena Sergeevna wrote in her diary: “16.39. Misha died.”

Sources

Bekhterev V. M. Hypnosis, Suggestion and Psychotherapy and Their Curative Significance. From lectures read to doctors and students of the Imp. Military-Med. Academy. St. Petersburg, 1911.

Bulgakov M. A. Collected Works. In 8 vols. Compiled, introd. art. and commentary by E. A. Yablokov. Moscow, 2007–2011.

Zemskaya E. A. Mikhail Bulgakov and His Relatives. A Family Portrait. Moscow, 2004.

Uborevich V. I. 14 Letters to Elena Sergeevna Bulgakova. Moscow, 2008.

Chudakova M. O. A Biography of Mikhail Bulgakov. Moscow, 1988.

Elena Bulgakova’s Diary. Compiled, textol. prep. and commentary by V. Losev and L. Yanovskaya. Introd. art. by L. Yanovskaya. Moscow, 1990.

Memoirs about Mikhail Bulgakov. Compiled by E. S. Bulgakova and S. A. Lyandres. Moscow, 1988.