9 Most Popular Legends About Vladimir Nabokov

Did Nabokov write novels on index cards? Did he suffer from insomnia? Was he thrilled by Kubrick’s Lolita? Did he buy Brodsky jeans? We examine what is true and what is not, and learn to cook eggs à la Nabocoque.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

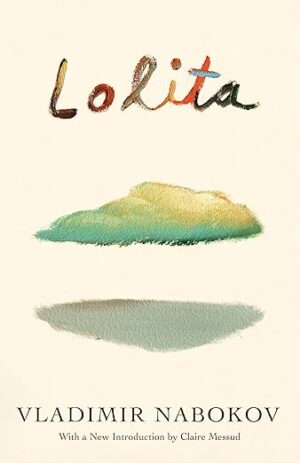

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Page Count: 317Year: 1955Products search A European professor develops a criminal obsession with his landlady’s 12-year-old daughter. To gain access to the girl, he marries her mother. When the mother dies unexpectedly, Humbert legally takes custody, launching a prolonged, twisted journey of psychological manipulation and abuse across the American highways. Their forced companionship, masked as a road trip, […]

€19.00 Login to Wishlist

Legend 1. Nabokov composed exclusively on index cards

Verdict: This is untrue.

Nabokov himself stated that after the age of 30, he wrote by hand on index-cards with a pencil, numbering them only when the set was complete. He rewrote each card numerous times, and his son Dmitri Nabokov compared the shoebox he used to store and rearrange the cards to the prototype of a future personal computer’s word-processing program.

However, during the first half of his writing career (approximately until he was thirty), Nabokov composed his stories and novels in a conventional manner, meaning in notebooks or on separate sheets, sometimes rewriting them three or four times. Manuscripts from his Russian period (such as drafts of The Gift) are held in the Library of Congress and confirm the use of notebooks.

Legend 2. Nabokov was a gourmet and lover of exquisite delicacies

Verdict: This is untrue.

Despite growing up in a wealthy St. Petersburg home with a chef, Nabokov remained extremely unpretentious in his gastronomic preferences. His letters to his wife, Véra, contain ascetic descriptions of meals, such as: “I had dinner early, at seven, and ate, my little chick, scrambled eggs and the little meats you know well.”

He preferred homemade food to restaurants. He declared: “I have ordinary habits, I am unpretentious in food, I would never exchange my favourite ham and eggs for a menu with a host of misprints.” When asked about his life, he replied that his life was “fresh bread with peasant butter and Alpine honey.”

In the autumn of 1972, clearly mocking a high-brow magazine’s request for his signature dish, Nabokov sent them a detailed recipe for eggs à la Nabocoque. The instructions essentially detail how to boil two eggs for precisely 200–240 seconds.

Legend 3. Nabokov was fundamentally uninterested in the Nobel Prize

Verdict: This is untrue.

Nabokov, who belongs to the impressive cohort of 20th-century writers who were overlooked for the Nobel Prize, did treat all sorts of literary accolades with disdain. Nevertheless, there are reasons to believe that he would not have refused the award had the Nobel Committee offered it to him.

Recently declassified internal documents from the Swedish Academy show that the Russian-American author’s name appeared on the lists of nominees during the 1960s. In the 1969 list, the author of Lolita was nominated by Slavic professor Simon Karlinsky.

A near-anecdotal story suggests Nabokov’s practical view of the prize: in late October 1969, the phone rang in the hotel room of the Nabokovs. Véra answered and heard: “Stockholm is calling you… Stockholm is calling you.” The line cut off. After a few moments of tense anticipation, another call came: a Swedish woman was asking Nabokov for help with her dissertation.

Legend 4. Nabokov suffered from insomnia

Verdict: This is true.

The writer struggled with insomnia throughout his life, failing to conquer it even with the nightly use of sleeping pills. His diaries from the Swiss period are peppered with the names and dosages of medications prescribed to him. In a notebook entry from November 1972, he scribbled a verse: “Got up, went to bed again. Dawn, like death, approached. If I don’t sleep soon, I’ll complain.”

However, Nabokov would not have been the great Nabokov if he hadn’t extracted literary benefit even from this painful ailment. Influenced by the English engineer and philosopher J. W. Dunne’s treatise An Experiment with Time (1927), he began to record his dreams—sometimes upon waking in the morning, sometimes in the middle of the night. These dream records were later published as a whole book, Insomniac Dreams: Experiments with Time (2017).

He refrained from straightforward interpretations in the manner of the hated Freud. Instead, he preferred to follow Dunne’s instructions and not try to recall the entire dream, focusing instead on one episode that he reconstructed in detail.

Legend 5. Nabokov bought jeans for Brodsky

Verdict: This is not entirely true.

The future Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky did wear jeans purchased with money provided by Nabokov. The purchase itself, however, was likely made by his wife, Véra, since Nabokov himself, according to Slavist Ellendea Proffer, did not concern himself with practical matters.

The legend stems from Nabokov’s meetings with Carl and Ellendea Proffer, the founders of Ardis Publishers. Nabokov entrusted the couple with money to buy gifts for Nadezhda Mandelstam and Brodsky, though he did not publicize his assistance to persecuted writers.

Brodsky’s enchantment with Nabokov’s prose ended after he heard his benefactor’s review of his poem Gorbunov and Gorchakov, in which Nabokov cited “incorrect stresses, the lack of verbal discipline, and verbosity in general” as flaws. Brodsky, who could not forgive the criticism, “immediately downgraded the brilliant prose writer Nabokov to the status of a failed poet.”

Legend 6. Nabokov visited Jerusalem

Verdict: This is untrue.

Véra and Vladimir Nabokov intended to visit Israel between 1975 and 1977. Nabokov received an official invitation from the Israeli ambassador to Switzerland and was to be a guest of the mayor of Jerusalem, Teddy Kollek. Furthermore, Nabokov’s close friend and former schoolmate from the Tenishev School, Samuil Rozov, lived in Israel.

However, the friends never met in Israel. Rozov died in December 1975. Nabokov immortalized Rozov in the novel Pnin as the minor character Samuil Izrailevich, an old friend not only of Professor Pnin but also of the narrator, who is transparently veiled under the name Vladimir Vladimirovich.

Legend 7. Nabokov despised the avant-garde

Verdict: This is true.

Nabokov, a conservative aesthetician, shocked interviewers by stating that avant-garde artists like “Malevich and Kandinsky mean nothing to me” and that he found Chagall’s painting “unbearably primitive and grotesque.” He preferred the artists whose work coincided with his childhood, such as Somov, Benois, Vrubel, and Dobuzhinsky (the latter was his painting teacher).

While Nabokov acknowledged that he appreciated Picasso’s graphic work, technique, and calm colour palette, he stated that beginning with Guernica, the Spaniard’s work did not resonate with him. Of the later work, he said: “And the tearful products of his old age I simply do not accept.” One of the few contemporary artists he liked was Balthus.

As an entomologist, Nabokov was a connoisseur of Old Masters (Hieronymus Bosch, Albrecht Dürer, etc.) who depicted butterflies. He dreamed of writing an illustrated book, Butterflies in Art, in which he would scientifically track and identify the species of butterflies in the paintings.

Legend 8. Nabokov was considered a brilliant university lecturer

Verdict: This is untrue.

Despite a long and successful academic career in America (including holding the title of “full professor”), Nabokov suffered from the necessity of teaching as a means of earning a living. He self-deprecatingly said that in his heart he always remained a meagre “hourly-rate” lecturer.

Former students recalled Nabokov as a rather dull professor who read pre-written lectures from paper with a strange accent. His apparent lack of interest in the audience served as a demotivator.

Nevertheless, his lecture notes, published in several collections, represent first-class philological analyses. At Cornell University, he taught a survey of Russian literature and a course on European literature of the 19th and 20th centuries (Flaubert, Tolstoy, Proust, Joyce).

Legend 9. Nabokov liked the film adaptation of Lolita directed by Kubrick

Verdict: This is untrue.

Lolita‘s bestseller status quickly led to a film adaptation. In 1959, Nabokov signed a lucrative contract and wrote the screenplay in Hollywood. However, upon viewing Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film, he was disappointed and realised the director “had left virtually nothing of his original ideas.”

Although he initially refrained from publicly criticising Kubrick, likely in hopes of future adaptations, Nabokov was later horrified by the banality of the sex scenes in the adaptation of his other book, Laughter in the Dark (1969). He believed that “pornographic tussles” had become a cliché, lacking “art and style.”

Nabokov was a keen cinephile, and during a walk in Montreux, he listed historical and literary episodes he would have liked to see on film, such as “Shakespeare in the role of Hamlet’s father’s Ghost” and “The Russians leaving Alaska, delighted with the deal. In the frame—an applauding seal.”