7 Secrets of The Master and Margarita

Why does the golden Falernian wine in Bulgakov’s novel change color to red? What weather is most often encountered in The Master and Margarita? Who and why tore off the buttons on the Master’s coat? We explain the meaning of these and other—at first glance insignificant—details.

On our website you can buy this book via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

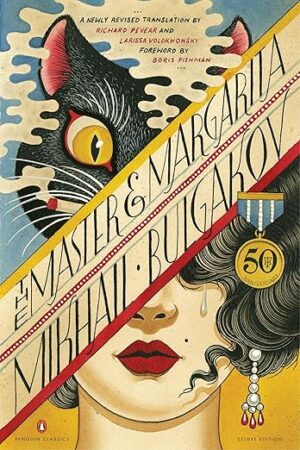

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

Page Count: 448Year: 1967Products search Imagine 1930s Moscow — a city constrained by bureaucracy, shortages, and state-enforced atheism — is suddenly visited by Satan himself, in the guise of Professor Woland, accompanied by his infernal retinue, including the absurdly dressed Koroviev and the massive, talking cat Behemoth. Woland’s visit is a devilish inspection and a session of black […]

€11.00 Login to Wishlist

1. The Secret of the Master’s Love for Roses

“— Don’t you like flowers at all? In her voice there was, as it seemed to me, hostility. I walked beside her, trying to keep pace, and, to my surprise, felt completely unconstrained. — No, I like flowers, just not these, — I said. — Which ones? — I like roses. At this, I regretted having said it, because she smiled guiltily and threw her flowers into the ditch.”

In the scene of meeting the Master, Margarita is carrying mimosas; in the Master’s basement, there is a vase with lilies of the valley on the table, and fragrant lilac grows outside the lovers’ window. Spring violets appear in the drafts—Margarita buys them at a flower shop on Okhotny Ryad before settling on a bench in the Alexander Garden and meeting Azazello, but Bulgakov later crossed out the bouquets of violets.

Roses appear most frequently in the novel, both in the Moscow and the Yershalaim chapters. “Long-awaited and mutually beloved roses” stand in the Master’s basement in the summer, and Margarita keeps one of them, already dried, along with the burnt manuscript in her closet. For the Devil’s Ball, she is sewn shoes from pale rose petals and her feet are washed with thick rose oil. Possibly the same oil whose scent torments Pilate in his residence. Incidentally, roses also grow in Pilate’s garden.

Why roses specifically? The writer’s third wife, Elena Sergeevna, recalled that Mikhail Afanasyevich loved roses. In 1929, when they first met, Bulgakov wrote her love letters and in them “sent red rose petals.” The commentators of The Master and Margarita, Irina Belobrovtseva and Svetlana Kul’yus, note that the rose in the novel’s space also symbolizes the earthly love between the Master and Margarita, which is inextricably linked with suffering, and simultaneously alludes to the Masonic layer of the text. In Mikhail Orlov’s book, The History of Man’s Dealings with the Devil, which Bulgakov studied while working on the novel, the Masonic “Sanctuary of the Rose Cross” is described, within whose walls the Grand Master conducts secret rituals. The Master’s love for roses emphasizes this character’s connection with the Masons, already established by the designation of the hero as a Master who renounced his name and former life for a spiritual path and self-improvement.

2. The Secret of the Falernian Wine’s Color

“— And again, I forgot, — Azazello exclaimed, clapping his forehead, — I’m completely worn out! Messire sent you a gift, — here he addressed the Master specifically, — a bottle of wine. I must point out that this is the very wine the procurator of Judea drank. Falernian wine. It was quite natural that such a rarity aroused great interest in both Margarita and the Master. Azazello produced a completely moldy jug from a piece of dark funeral brocade. They smelled the wine, poured it into glasses, and looked through it at the light in the window disappearing before the storm. They saw everything turn the color of blood.”

While working on the Yershalaim chapters, Bulgakov looked for interesting everyday details in the sources available to him. In the excerpts he titled “Materials for the Novel,” one can find notes on clothing (“The chlamys was fastened with a shiny buckle on the right shoulder”), plants (“olive trees and large fig trees”), and writing accessories of the time (Bulgakov uses them for a very small detail in the scene with Pilate: “A chair was already prepared on the mosaic floor by the fountain, and the procurator, without looking at anyone, sat down in it and held out his hand. The secretary respectfully placed a piece of parchment in this hand”).

Bulgakov may have learned that the procurator drank Falernian and Caecuban wine from Gaston Boissier’s book, Roman Religion from Augustus to the Antonines, or Anatole France’s short story, The Procurator of Judea, published separately in Moscow in 1928. Boissier and France do not mention the wine’s color, but Bulgakov could have learned that Falernian wine was golden in color and second in quality only to Caecuban from a short article titled “Falernian Wine” in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary. The complete collection of the famous encyclopedia stood on the writer’s bookshelves in his study—he made excerpts from it about Sabbaths, Pilate, Jerusalem, and other things. In the “Materials for the Novel,” he made a note: “Falernum vinum — golden wine.”

Falernian wine was produced in the southern part of Italy, in the region called Campania, at the foot of Mount Massicus. According to legend, the god of wine Bacchus visited a local resident named Falernus and, in reward for his hospitality, presented him with a grapevine from which the famous Falernian grape originated. The best wine was considered to be that aged for at least 15 years, although it was still inferior to Caecuban, made from grapes grown in the Caecuban region, located in the Lazio area, south of Rome. Famous Italic wines were praised by Horace, Pliny, and Martial.

According to a very plausible version by Irina Belobrovtseva, Svetlana Kul’yus, and Boris Sokolov, Bulgakov deliberately changed the color of the Falernian wine from golden to blood-red in the pre-storm light of the Moscow day to emphasize the importance of what was happening in the Master’s basement: the heroes undergo initiation, and the transition to another existence is accomplished through poisoning and death.

3. The Secret of the Thunderstorm

In The Master and Margarita, a thunderstorm and downpour are the most frequent weather phenomena in both the Moscow and Yershalaim chapters. Here are the most famous lines of the novel—the beginning of the manuscript, reborn from the ashes, which Margarita reads after reuniting with her lover, the Master:

“The darkness that had come from the Mediterranean Sea covered the city hated by the procurator. The hanging bridges connecting the temple with the terrible Tower of Antonia disappeared, a chasm descended from the sky and flooded the winged gods above the hippodrome, the Hasmonean Palace with its embrasures, the markets, the caravanserais, the alleys, the ponds… Yershalaim vanished—the great city, as if it had never existed in the world. Everything was swallowed by the darkness that terrified all living things in Yershalaim and its environs. A strange cloud was brought from the sea toward the end of the day, the fourteenth day of the spring month of Nisan.”

Bulgakov gives an almost identical description of Moscow before Woland’s departure from the capital:

“This darkness, which had come from the west, covered the colossal city. The bridges, the palaces disappeared. Everything vanished, as if it had never been in the world. A single fiery thread streaked across the sky. Then a blow shook the city. It was repeated, and the storm began. Woland ceased to be visible in its gloom.”

Boris Mikhailovich Gasparov identified several lines, or channels, in the novel’s structure that permeate the entire text and connect its parts into a single organism, and he called them leitmotifs. One such leitmotif, emphasizing the parallelism of the two stories and the cyclicality of time in the novel’s space, became the thunderstorm.

The thunderstorm accompanies both minor troubles (the kidnapping of Varenukha, Ivanushka’s attempts to describe Berlioz’s death) and major ones (a storm breaks over Yershalaim during Yeshua’s execution; a huge cloud covers the city when the Master and Margarita visit Homeless in Stravinsky’s clinic before leaving the capital).

For the writer himself, a thunderstorm was a harbinger of failure, although he was not particularly superstitious. This is what Elena Sergeevna Bulgakova told Marietta Chudakova about her husband’s work on the play Batum, which ended in disaster:

“When he read Batum that summer—there was a thunderstorm every time! One day Kalishyan invited us to the theater for a reading. It was hot, July, and I was wearing a light, airy, sleeveless dress. And while we were driving in the car—a terrible thunderstorm began! We drove up to the theater—there was a poster for the reading of Batum, painted in watercolor, all streaked with rain. — Give it to me! — Misha said to Kalishyan. — Oh, why would you want it? You know what kind of posters you’ll have? Completely different ones! — I won’t see any others.”

The play indeed never saw the stage: presented to Stalin (he was the main character of the text), it received a negative review and was banned from production. After this, Bulgakov became seriously ill and never recovered.

4. The Secret of the Torn-Off Buttons

The Master tells Ivan Homeless how someone knocked on his window one night in the first half of October. The next time he found himself near his basement was in January:

“— Yes, so, in the middle of January, at night, in the same coat, but with the buttons torn off, I was huddled from the cold in my courtyard.”

And although Bulgakov gives no additional details, contemporaries were well aware of how a person could end up on the street without buttons after a knock at the door.

In her commentary on the Moscow part of the novel, Marietta Chudakova listed Soviet realities familiar to Muscovites in the 1930s: trials of currency speculators, universal suspicion and spy mania, sealed living quarters (usually after a search, and in the novel—after Berlioz’s death), mysterious disappearances of people (Margarita is sure that Azazello is an agent sent to arrest her), and others. All this was well known to the writer and his contemporaries. They knew that in prison, the arrested had their belts and shoelaces taken away and their buttons cut off.

The drafts contain much more “prison” specifics, which Bulgakov later abandoned. He describes in detail how Nikanor Ivanovich Bosoy is brought to prison after his arrest (the novel’s outline includes the chapter “Bosoy in Prison“):

“Nikanor Ivanovich’s initial expectations seemed to be justified: his companions drove him at sunset to the outskirts of Moscow to an unappealing building, which Nikanor Ivanovich knew by hearsay was a prison. The subsequent impressions also seemed to be prison-like. Nikanor Ivanovich had to go through a series of tedious formalities. Nikanor Ivanovich was recorded in some book, his clothing was inspected, and Nikanor Ivanovich was deprived of his suspenders and belt.”

The Master in the drafts is not in a lunatic asylum but in a camp, and the evil spirits rescue him precisely from there:

“[Fielov was transformed. He was wearing an ear-flapped fur hat and a long sheepskin coat.] <…> A quilted men’s wadded jacket was on him. Soldier’s trousers, rough high boots. Covered in dirt, his hands wounded, his face overgrown with reddish stubble. The man, squinting from the bright light of the chandeliers, trembled, looked around, his eyes shining with alarm and suffering.”

As we know, Bulgakov later decided to place the Master in a lunatic asylum, but the storyline of arrest based on a denunciation and prison was left as a subtle hint. In some sense, this line can be called autobiographical—he was not arrested, but he was summoned for interrogations (once he traveled to the Lubyanka under escort), so the writer knew about this part of the everyday life of a Soviet citizen firsthand.

5. The Secret of Azazello’s Hair Color

Bulgakov wrote the novel for more than ten years; new characters appeared (for example, the Master and Margarita were not in the early drafts of the novel), and old ones changed names, appearance, or character. Azazello, from Woland’s retinue, bore the name Boniface in the first editions and was much more repulsive than in the final version of the text:

“One eye had leaked out, his nose was sunken. The mug was dressed in a short kamzolchik… …And fangs grew wherever they pleased. <…> Furthermore, a hump.”

The character later became more presentable (only one fang stuck out, and the leaked eye became just a film), but one thing remained unchanged in his appearance—red hair.

There are several explanations for this. The first and most obvious: Azazello is a rogue and deceiver, part of Satan’s retinue, and cunning and treachery have been attributed to red-haired people since the Middle Ages. Their lineage was probably traced back to the red-haired Judas: Bulgakov could have learned that Judas was red-haired from the book The Life of Jesus Christ by Frederic Farrar, which he studied while gathering materials for the novel.

In the book Red: The History of a Color, historian Michel Pastoureau writes about superstitions that emerged at the end of the Middle Ages: “…meeting a red-haired person on the road is a bad omen, and women with hair of that color are either witches or harlots.” The witch Hella in Woland’s retinue is also red-haired.

Another explanation links Azazello’s hair color to clownery and buffoonery. The jester’s aspect of his image is especially noticeable in the novel’s drafts. In an early edition, Azazello is dressed in striped, multicolored clothes embroidered with jingle bells. Irina Belobrovtseva and Svetlana Kul’yus pointed out in their commentary on the novel that the prototype for Azazello’s buffoonish traits was the Red Clown (Ryzhy). This clown persona appeared at the end of the 19th century and quickly gained popularity—both solo and in a duet with the White Clown: “In the Russian pre-revolutionary circus, he also performed solo (solo-R., R. by the carpet).” Grotesque and buffoonery are very characteristic of the Red Clown persona. Of course, this description is closer to the Koroviev—Behemoth pair, but Azazello is also not alien to buffoonish grotesque. Lidiya Yanovskaya, noting this side of his image in Azazello, shows how toward the end of the novel, the “demonic” features in him “become more insistent.” In the chapter “Forgiveness and Eternal Shelter,” the reader finally sees the true Azazello: “Now Azazello flew in his true form, as a demon of the waterless desert, a demon-murderer.”

6. The Secret of the Lunar Guest

“Margarita pleaded with the Master in a trembling voice: — Drink, drink. Are you afraid? No, no, trust me, they will help you. The patient took the glass and drank what was in it, but his hand trembled, and the empty glass broke at his feet. — To good luck! To good luck! — Koroviev whispered to Margarita. — Look, he’s already coming to his senses. Indeed, the patient’s gaze was no longer so wild and restless. — But is it you, Margo? — asked the lunar guest. — Don’t doubt it, it’s me, — answered Margarita. — Again! — ordered Woland. After the Master drained the second glass, his eyes became alive and meaningful. — Well now, that’s better, — said Woland, squinting, — now let’s talk.”

The action of The Master and Margarita often unfolds at night, by the moon or moonlight: in the drafts, the epilogue was even called “Victims of the Moon,” but Bulgakov later abandoned this idea. The moon appears already in the first chapters:

“The streetlights were already lit on Bronnaya, and a golden moon shone over the Patriarch’s Ponds, and in the moonlight, always deceptive, it seemed to Ivan Nikolaevich that the man was standing, holding not a cane but a sword under his arm.”

In the novel, the moon accompanies the evil spirits, traditionally active at night, and the Master—a hero unrelated to the evil spirits. We first see the Master in the moonlight: “a mysterious figure emerged on the balcony, hiding from the moonlight, and shook a finger at Ivan.” And in the epilogue, he appears in Ivan Nikolaevich Ponyryov’s dreams in streams of moonlight:

“Then the lunar path boils up, a lunar river begins to gush from it and spills out in all directions. The moon reigns and plays, the moon dances and frolics. Then a woman of immense beauty forms in the stream and leads to Ivan by the hand a bearded man who looks around timidly. Ivan Nikolaevich immediately recognizes him. This is—that number one hundred and eighteen, his night guest.”

Like the thunderstorm, the moon can be called a leitmotif, connecting two heroes from different worlds: Yeshua in the Yershalaim chapters and the Master in the Moscow chapters. Yeshua, like the Master, is associated with the moon. Pilate dreams that he walks along a moonlit road with the wandering philosopher (“I constantly see a moonbeam in my sleep”), and along the same moonlit road he leaves the gorge where he was imprisoned for twelve thousand moons with his dog.

Svetlana Kul’yus and Irina Belobrovtseva note that Bulgakov undoubtedly knew that Christ’s crucifixion was accompanied by an eclipse. His excerpts from David Strauss’s book The Life of Jesus are preserved in the “Materials for the Novel“: “The cause of the darkness, which Luke defines more precisely as an eclipse of the sun, could not have been a natural eclipse: at that time, it was the Passover full moon.”

But Bulgakov was interested in the moon not only in connection with Yeshua Ha-Notsri and the Master. In the late 1930s, he kept observations of the moon. “Moon! Check the moon!” is written in the margins of the novel’s manuscript. Researchers Irina Belobrovtseva and Svetlana Kul’yus quote the writer’s characteristic notes about the moon: “Moon [drawing is included here] 10.III.1938 at twenty to eleven in the evening it was like this: (white) (visible from the windows facing B. Afanasyevsky Lane). Soon disappeared (clouds?).” Or: “Moon 29 March 1939 at about 10 p.m. was on the left hand, high up, if looking from the windows of my room, in the form of [a drawing of a tilted crescent follows].”

7. The Secret of the Chess Game

Here is the description of the game between Woland and Behemoth:

“Meanwhile, confusion reigned on the board. The utterly distraught King in a white mantle paced on the square, raising his hands in despair. Three white pawn-landsknechts with halberds looked in confusion at the Officer, who was brandishing a sword and pointing forward, where, in adjacent squares, white and black, Woland’s black riders were visible on two hot horses, pawing the squares. Margarita was extremely interested and struck by the fact that the chess pieces were alive. The Cat, putting the binoculars away from his eyes, quietly nudged his King in the back. The latter despairingly covered his face with his hands. <…> <…> The White King finally realized what was wanted of him, suddenly stripped off his mantle, threw it on the square, and ran off the board. The Officer threw the discarded royal attire over himself and took the King’s place.”

Researchers propose different theories about what gambit was being played on the board. The two most likely games are considered to be: The first was played at the Moscow International Chess Tournament in 1935 between Mikhail Botvinnik and Nikolay Ryumin. The tournament was widely covered in the press, and the Botvinnik—Ryumin game was awarded a prize for its beauty. According to the other version, the prototype for the chess battle in the novel was the Mayet—Löwenthal game.

Margarita is struck in the novel by the fact that the chess pieces on the board are alive. In early editions of the novel, the scene was much more concise:

“The one sitting at that moment tapped a golden figure on the board and said: — You are playing terribly, Behemoth. — I, Messire, — the large black Cat respectfully answered his partner, embarrassed, — [I didn’t notice the pawn] I miscalculated. The local climate has a bad effect on me. — The climate has nothing to do with it, — said the one sitting, — you’re simply a chess cobbler. The Cat chuckled flatteringly and tilted his King.”

According to Vladimir Pimonov’s assumption, this reflects the writer’s memories of the “living” chess game between Mikhail Botvinnik and Nikolay Ryumin, which took place in 1934 at a Moscow stadium. Weightlifters were the Kings, tennis players were the Queens, track and field athletes were the Rooks, cyclists depicted the Bishops (Officers), and javelin throwers were the Knights. Football teams, dressed in black and white, became the Pawns. Marietta Chudakova adds that the “living” chess pieces played by Woland symbolize his power over people’s destinies, and notes that the Botvinnik—Ryumin tournaments of 1934 and 1935 took place several years before Bulgakov worked on the detailed chess scene. Nevertheless, the impressions from these games could have remained in Bulgakov’s memory: he loved chess from his youth and played it with the passion of a serious amateur.

His first wife, Tatyana Nikolaevna, recalled the winter of 1917 in Saratov: “I don’t remember that time well, I only remember that my father and Mikhail were constantly playing chess…” Later, in the 1920s, he played chess with his close friend, the philologist Nikolay Lyamin, and in the 1930s his constant chess partners were the satirical writer Arkady Bukhov, the theatrical designer Sergey Topleninov, who made remarkable theatre models, and the doctor Andrey Arendt, whose ancestors once treated Pushkin. According to Elena Sergeevna’s testimony, Bulgakov even taught her younger son to play chess:

“Misha taught him to play, and when Sergey won (you understand, this was necessary for pedagogical purposes), Misha would write me a note: ‘Give Sergey half a bar of chocolate.’ Signature. Although I was sitting in the next room. Or they would write a conspiratorial letter and put it in the mailbox on the door and constantly urge me to look: is there anything in the box…”

It is not surprising that this passion found reflection in the novel, which occupied almost all the writer’s thoughts in the 1930s. In one of the early editions, Homeless, chasing Woland, runs to the entrance of a house in Savelyevsky Lane and hears from the doorman: “You came in vain, Count, Nikolay Nikolaevich went to Boris’s place to play chess.” Nikolay Nikolaevich is that same Lyamin, an avid chess player and friend of Mikhail Bulgakov. The author later crossed out this episode, as he gradually removed obvious autobiographical traces from the novel, but chess remained.

Sources

Belobrovtseva I. Z., Kulyus S. K. The Novel “The Master and Margarita” by M. Bulgakov. A Commentary. Moscow, 2007.

Bulgakov M. A. The Master and Margarita: Complete Collection of Drafts of the Novel. Main Text. In 2 vols. Moscow, 2019.

Bulgakov M. A. The Master and Margarita. St. Petersburg, 2001.

Gasparov B. M. Literary Leitmotifs. Essays on Russian Literature of the XX Century. Moscow, 1994.

Jovanović M. Once More on the Chess Scene. 64. Shakhmatnoye Obozreniye (Chess Review). No. 2. 1986.

Orlov M. A. A History of Man’s Relations with the Devil. St. Petersburg, 1904.

Pastoureau M. Red. The History of a Color. Moscow, 2023.

Pimonov V. The Riddle of Margarita. 64. Shakhmatnoye Obozreniye (Chess Review). No. 17. 1985.

Sokolov B. V. Bulgakov. The Master and the Demons of Fate. Moscow, 2016.

Sokolov B. V. The Novel “The Master and Margarita” by M. Bulgakov. Essays on the Creative History. Moscow, 1991.

Farrar F. W. The Life of Jesus Christ. St. Petersburg, 1893.

Chudakova M. O. A Biography of Mikhail Bulgakov. Moscow, 2024.

Chudakova M. O. Mikhail Bulgakov: His Partners, His Works. 64. Shakhmatnoye Obozreniye (Chess Review). No. 18. 1985.

Yanovskaya L. M. Notes about Mikhail Bulgakov. Moscow, 2007.

Memoirs about Mikhail Bulgakov. Moscow, 1988.

Elena Bulgakova’s Diary. Moscow, 1990.

Circus. Small Encyclopedia. Moscow, 1979.