7 Secrets of Doctor Zhivago

Why is Lara’s seducer named Komarovsky? Why does Yuri Zhivago’s father travel to the Irbit Fair? What is a predvarilka? We talk about the subtle but important details of one of the most controversial novels of the 20th century.

On our website you can buy this book via the link.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

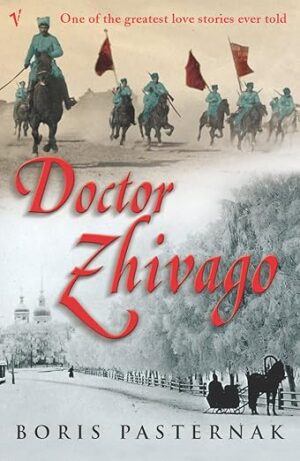

Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

Page Count: 512Year: 1957Products search Zhivago marries the gentle Tonya, but his destiny is tragically entwined with the passionate, elusive Larisa (“Lara”) Antipova, a woman whose life is scarred by an older predator and whose husband transforms into the fearsome Red commander, Strelnikov. As the world fragments into chaos, the doctor struggles to practice his art and preserve […]

€20.00 Login to Wishlist

1. The Secret of Yuri Zhivago’s Father

Here is what we know about Yuri’s father:

“While his mother was alive, Yura did not know that his father had long ago abandoned them, traveled to various cities in Siberia and abroad, was carousing and womanizing, and that he had long ago squandered and scattered their million-ruble fortune to the wind. Yura was always told that he was either in St. Petersburg or at some fair, most often the Irbit Fair.”

It is quite obvious that the elder Zhivago, a wealthy man engaged in commercial activity, traveled to the Irbit Fair, as before the revolution it was the largest fair in Russia (after the Nizhny Novgorod Fair) and the closest to Siberian cities. However, there was another reason for these trips: later we learn that the hero’s father has a second family in Siberia.

For Pasternak himself, this place has another, symbolic meaning. Irbit is located in the Urals, which divides Europe and Asia. Pasternak wrote about the importance of crossing this border earlier in his novella The Childhood of Luvers (1917–1918):

“In her enchanted mind, ‘the border of Asia’ arose in the form of some phantasmagorical boundary… <…> Zhenya resented the boring, dusty Europe, which clumsily delayed the onset of the miracle.”

Evgraf, Yuri’s half-brother, was a Siberian: he had a “dark face with narrow Kirghiz eyes.” And here is how Yuri describes the house in Omsk where Evgraf lived as a child:

“And lately I’ve had the feeling that with its five windows this house is looking at me with an unkind gaze across the thousands of versts separating European Russia from Siberia, and sooner or later it will put a hex on me.”

It turns out that a kind of high-tension line is stretched between Moscow and Omsk, grounded somewhere in the middle, in the area of the Ural trade town of Irbit. The father, whom Yuri mostly imagines being at the Irbit Fair, is torn between his legitimate and illegitimate families, between his two sons. He never manages to cross this conditional border: in his frenzy, he loses himself, loses his mind, and commits suicide.

2. The Secret of the Komarovsky Surname

Here is what the novel says about Lara Guishar’s relationship with the lawyer Viktor Komarovsky:

“If Komarovsky’s intrusion into Lara’s life had only aroused her aversion, Lara would have rebelled and broken free. But the matter was not so simple.”

What was Pasternak drawing on when describing the tormented relationship between Lara and Komarovsky? The plot is based on a real story involving Pasternak’s youth friends. In the summer of 1910, he often visited his friend Alexander Shtikh’s dacha and met his cousin Elena Vinograd there. Boris and Alexander were 20 years old; Elena was 14.

Later, in 1917, Vinograd told Pasternak that there was a love affair between her and her cousin that caused both of them suffering. Pasternak’s poem “Our Thunderstorm” from the book My Sister—Life, dedicated to Elena, is dated to the same time:

К малине липнут комары [Mosquitoes stick to the raspberries]. Однако ж хобот малярийный, Как раз сюда вот, изувер [torturer], Где роскошь лета розовей?!

The fact is that the surname Shtikh means “sting” or “prick” in German. Pasternak compares the seducer to a torturer-mosquito stinging its victim with a malarial proboscis. Through this association, Pasternak invents the surname for Lara’s fateful seducer—Komarovsky (from komar, the Russian word for mosquito).

3. The Secret of the Predvarilka

One of the novel’s heroines, Shura Schlesinger, appears at a party in the Zhivago family, organized after Yuri’s return from the front, and lectures Yuri Andreevich:

“Come with me sometime, Yurochka. I’ll show you people. You must, you must, do you understand, like Antaeus, touch the earth. Why are you staring? Do I surprise you, perhaps? Don’t you know that I am an old warhorse, an old Bestuzhevka, Yurochka. I was acquainted with the predvarilka, I fought on the barricades. Of course! What did you think? Oh, we don’t know the people! I’ve just come from their midst. I’m setting up a library for them.”

Why does Shura call herself a Bestuzhevka and what is this acquaintance with the predvarilka? In the late 1870s, the Higher Women’s Courses were opened in St. Petersburg. The first director was the famous historian Konstantin Bestuzhev-Ryumin. Soon enough, the political unreliability of the students was brought to the attention of the management: the courses were even considered for closure. Indeed, many Bestuzhevki—as the students were called—were connected with Populist organizations, held radical left-wing views, and later, in 1905–1907, sympathized with and even actively participated in revolutionary events. Lenin’s sisters—Anna and Olga—as well as Nadezhda Krupskaya, studied at the Bestuzhev Courses.

Thus, Shura is not just casually mentioning that she studied at the women’s courses, but is presenting herself as a seasoned revolutionary. Her speech contains another unfamiliar word—predvarilka. This was the common name for the House of Preliminary Detention, or the Shpalernaya Prison (Shpalerka). The first investigative “model prison” in Russia opened in St. Petersburg in 1875 on Shpalernaya Street, 25.

Of the 317 solitary cells, 32 were for women. Many participants in the revolutionary movement were held there—from the Populists to Lenin. It is easy to notice that Pasternak describes Shura ironically: unlike the sincere revolutionaries Pavel Ferapontovich Antipov or Kupriyan Savelevich Tiverzin, she throws around bombastic phrases and admires herself.

4. The Secret of the Commissar

Leaving Melyuzeevo at the end of the summer of 1917, Doctor Zhivago meets the new commissar, who has been sent to the district center to quell a rebellious regiment in connection with an impending offensive:

“The rumors about the commissar were confirmed. He was a slender and trim, completely callow youth, who burned like a candle with the highest ideals. They said he was from a good family, perhaps even the son of a senator, and was one of the first to lead his company to the State Duma in February. His surname was Gintse or Gints; it was unclear when the doctor was introduced to him. The commissar had a correct Petersburg accent, very clear, with a slight Ostsee (Baltic German) sound.”

Gints has a very real prototype: Fyodor Fyodorovich Linde. During the February Revolution, he led the soldiers who joined the uprising, was a member of the executive committee of the Petrograd Soviet, and actively participated in subsequent events. It was he who, in April 1917, led the Finland Regiment to the Mariinsky Palace, demanding the resignation of the head of the Provisional Government, Pavel Milyukov.

Like many at the time, Linde admired Alexander Kerensky, who headed the government in the summer, and imitated him, including acquiring a French-style tunic (frenche) and breeches (galife). Gints did the same:

“He was in a tight frenche. He was probably uncomfortable that he was still so young, and to appear older, he peevishly twisted his face and assumed a feigned stoop. To do this, he plunged his hands deep into the pockets of his galife and raised his shoulders at the corners of his new, stiff shoulder straps…”

Gints’s Ostsee accent also goes back to Linde, who was born into a Polish-German family and spoke with a distinct German accent. Finally, Gints’s death, killed by soldiers, is based on the death of Linde, which was reported in all the newspapers in 1917. The fate of the commissar is symbolic: by killing his hero, Pasternak diagnoses the revolution, whose wheel has already turned against those who devotedly serve it.

5. The Secret of the Three Partisans

When Yuri Zhivago is traveling from Yuryatin to Varykino, he is stopped and captured by partisans at a crossroads:

“Ahead, the road split in two. Near it, a sign reading ‘Moro and Vetchinkin. Seeders. Threshers’ glowed in the light of dawn. Three armed horsemen stood across the road, blocking it. A Realist in a uniform cap and a peasant coat crossed with machine-gun belts, a Cavalryman in an officer’s greatcoat and a Kubanka hat, and a strange, like a masquerade mummer, fat man in quilted trousers, a padded jacket, and a low-slung priest’s hat with wide brims.”

Who are these people, what does the meeting with them mean, and why does Pasternak describe the trio in such detail?

- The Realist is a student of a real school: unlike classical gymnasiums, where teaching emphasized ancient languages, these secondary educational institutions had a focus on mathematics and natural sciences.

- The Cavalryman in an officer’s greatcoat and a kubanka (a short papaha or Cossack hat) is a professional soldier, obviously a career officer who went over to the Red Army, having served in the Kuban or another Cossack regiment. The hat is shortened because Cossacks who joined the Reds would trim their papahas and replace the cockades with red stars.

- The third partisan is the fat man. By his clothing, one can guess that he is either a former priest or someone who previously had a connection to the Church (indicated by the priest’s hat).

The protagonist’s meeting with the three travelers shows how the revolution changes the identity of its participants. The Realist boy is girded with machine-gun belts, the Cossack officer has sided with the enemy, and the former priest takes up arms. And not just them, but other characters in the novel as well: for example, the hard-working peasant Pamfil Palykh becomes a cold-blooded killer, and the kind and honest Pavel Antipov turns into the merciless Strelnikov.

6. The Secret of Yuryatin

When the train carrying the Zhivago family approaches Yuryatin, the doctor sees the city bathed in the rays of the rising sun from the carriage window:

“About three versts from Razvil’ye, on a hill higher than the suburb, a large city, a district or provincial capital, emerged. The sun gave its colors a yellowish tint, the distance simplified its lines. It clung to the elevated ground in tiers, like Mount Athos or a hermit’s skete in a cheap popular print, house upon house and street above street, with a large cathedral in the middle at the very top. ‘Yuryatin!’ the doctor realized excitedly.”

The prototype for Yuryatin is considered to be Perm. Why is the first encounter with the city described as something wonderful, why does this place resemble an image from a magical fairy tale? Pasternak hints at the mythological city—the New Jerusalem: it was depicted exactly like this—on a hill, with a temple in the middle and tiers of buildings—by icon painters. Yuryatin is bathed in bright morning sun, the yellow colors evoke the golden glow that emanates from the Heavenly City: “…and the city was pure gold, like clear glass.”

The image of a city on a hill, which seems like paradise to the hero, where a new life can be found, is found earlier in Pasternak’s prose. In the novella Safe Conduct, the German city of Marburg is described: “I stood, head thrown back and gasping for breath. Above me rose a dizzying slope on which the stone models of the university, the town hall, and the eight-hundred-year-old castle stood in three tiers.” Yuryatin plays the same role in Zhivago’s life that Marburg played in Pasternak’s own life: in these cities, both the author and his hero met extraordinary love, began a new life, and wrote their best poems.

7. The Secret of the Zemstvo

Here is what Yuri Zhivago writes in a letter to his wife about his new acquaintance, Larisa Antipova, in the summer of 1917:

“Zemstvo [local self-governance], which previously existed only in provinces and districts, is now being introduced in smaller units, in volosts [rural districts]. Antipova left to help a friend of hers who is working as an instructor precisely on these legislative innovations.”

What is so important about Antipova working as an instructor in the zemstvos? Public activities of this kind in the summer of 1917 could not but command respect. Peasants had mixed feelings about the zemstvo reform: many were dissatisfied with granting voting rights to women, secret balloting, and the participation of representatives of other social estates in the elections. Therefore, people working on the reform often faced aggression. The first elections took place in August. There was a lot of organizational work, and volunteers, mostly from the progressive youth, were called upon for help locally. Pasternak was well aware of this: Elena Vinograd, mentioned earlier, responded to the call to participate in the creation of zemstvo self-government bodies and went with her brother from Moscow to the Saratov province.

By mentioning Lara’s occupation, Zhivago denies being even slightly infatuated with Antipova. But it is the story about the zemstvo reform that gives him away: this is undoubtedly an indication that Lara’s integrity, her selflessness, courage, and openness to change admire Yuri Andreevich.

Sources

Komarov N. A. Military Commissars of the Provisional Government (March — October 1917). Dissertation for the degree of Candidate of Historical Sciences. Moscow, 2001.

Krasnov P. N. On the Internal Front. Archive of the Russian Revolution. Vol. 1. Moscow, 1991.

Matveev M. N. The Drama of the Volga Zemstvo. Novyi Mir (New World). No. 7. 1997.

Pasternak E. V. The Summer of 1917 in “My Sister — Life” and “Doctor Zhivago”. Pasternak Readings. Moscow, 1998.

Pasternak E. B., Pasternak E. V. The Life of Boris Pasternak: A Documentary Narrative. St. Petersburg, 2004.

Boris Pasternak’s “Marburg”: Themes and Variations. Moscow, 2009.