10 of the Most Witty Excerpts from Chekhov’s Letters

Chekhov was witty not only in his works but also in life. We offer you a selection of quotes from Chekhov’s letters.

-

Buy eBook

Editor's Pick

Editor's PickFayina’s Dream by Yulia Basharova

Page Count: 466Year: 2025Products search A mystical, satirical allegory about the war in Grabland, featuring President Liliputin. There is touching love, demons, and angels. Be careful! This book changes your thinking! After reading it, you’ll find it difficult to sin. It is a combination of a mystical parable, an anarchy manifesto, and a psychological drama, all presented in […]

€10.00 Login to Wishlist -

Buy Book

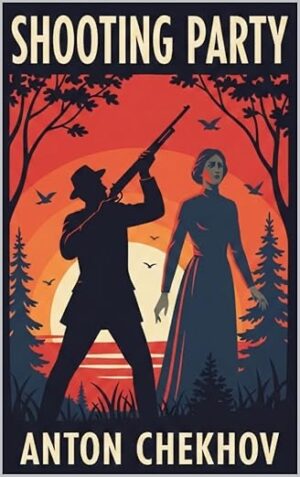

Drama on the Hunt (The Shooting Party) by Anton Chekhov

Page Count: 402Year: 1884READ FREEProducts search This isn’t just a detective story where the killer is known from the first page; it’s a deep psychological drama where every character wears a mask, and the truth is as elusive as a beast in the thicket. You’ll witness a tangled love triangle where jealousy, desire, and deceit intertwine with a fatal […]

€23.00 Login to Wishlist

1. On Indecent Bird Behavior

“<…> Spring has already begun, and all the feathered creatures, having forgotten all decency, satisfy their natural needs and thus turn my garden and my woods as it were into houses of tolerance.”

To Alexander Chekhov. Melikhovo, March 27 and 29, 1895

2. On Money

“<…> Spring is approaching, the days are getting longer. I want to write, and it seems to me that this year I will write as much as Potapenko. And I need money like hell. I need 20 thousand a year income, as I can no longer sleep with a woman unless she is wearing a silk chemise. Besides, when I have money, I feel as if I am on clouds, slightly drunk, and I cannot help but spend it on all sorts of nonsense. The day before yesterday was my name day; I expected presents and did not receive a damn thing.”

To Alexei Suvorin. Moscow, January 19, 1895

3. On Marriage

“…obviously, you have a fiancée whom you want to get rid of as soon as possible; but excuse me, I cannot get married at the present time, because, firstly, I have bacilli in me, very doubtful tenants; secondly, I have no money at all, and, thirdly, I still feel that I am very young. Allow me to walk around for another two or three years, and then we’ll see—perhaps I will get married indeed. But why do you want a wife to ‘rouse me up’? Life itself is already rousing me up, rousing me fast enough.”

To Fyodor Schechtel. Melikhovo, December 18, 1896

4. On Fickle Weather

“<…> Our weather is engaging in prostitution.”

To Nikolay Leykin. Moscow, December 8, 1886

5. On Kisses

“<…> Thank you for your wishes regarding my marriage. I told my fiancée about your intention to come to Yalta to deceive her a little. She said that when ‘that naughty woman’ arrives in Yalta, she will not let me out of her embrace. I remarked that being in an embrace for so long in hot weather is unhygienic. She took offense and became thoughtful, as if trying to guess in what environment I had acquired this façon de parler (way of speaking), and a little later said that the theater is evil and that my intention not to write any more plays deserves all praise—and asked me to kiss her. To this, I replied that now, in my rank as an Academician, it is indecent for me to kiss often. She burst into tears, and I left.”

To Olga Knipper. Yalta, February 10, 1900

6. On Clever Frogs

“<…> …You are badly raised, and I do not regret that I once punished you with a whip. Understand that the daily expectation of your arrival not only tires us but also incurs expenses: usually at dinner, we eat only yesterday’s soup, but when we expect guests, we also prepare a roast of boiled beef, which we buy from the neighbor’s cooks.

We have a magnificent garden, dark alleys, secluded corners, a river, a mill, a boat, moonlit nights, nightingales, turkeys… The frogs in the river and the pond are very clever. We often go for walks, during which I usually close my eyes and make my right hand a pretzel, imagining that you are walking with me arm in arm.”

To Lidia Mizina. Bogimovo, June 12, 1891

7. On How to Write

“<…> My advice: in a play, try to be original and as intelligent as possible, but do not be afraid to appear foolish; you need freedom of thought, and only he who is not afraid to write stupid things is a free thinker. Do not smooth out, do not polish, but be clumsy and bold. Brevity is the sister of talent. Remember, by the way, that declarations of love, wives’ and husbands’ infidelities, widows’, orphans’, and all other tears have long been described. The plot must be new, and the story structure (fabula) can be absent.”

To Alexander Chekhov. Moscow, April 11, 1889

8. On Syphilis and Gas

“<…> From the description of your illness, I concluded that you have the most terrible syphilis and a huge fistula of the anus, formed as a result of the continuous release of gas.”

To Alexander Chekhov. Melikhovo, September 22 or 23, 1895

9. On Members and Eggs

“Thanks to the damned herb that you gave me, all my land is covered with little members in erecktirten Zustande (in an erected state). I planted the herb in three places, and all these three places already look as if they want to copulate.

Speaking of members, one cannot be silent about eggs.

The eggs received from you have been placed under a chicken. Thank you for the multiplication of our farm! If the chicks hatch successfully, I will arrange a special room for them by winter and will look after them myself.”

To Fyodor Schechtel. Melikhovo, June 7, 1892

10. On Sheep

“<…> Yesterday and the day before was a wedding, a real Cossack one, with music, women’s goat-voice singing, and outrageous drinking. Such a mass of motley impressions that it is impossible to convey in a letter, and I will have to postpone the description until my return to Moscow. The bride is 16 years old. They were married in the local cathedral. I was the groomsman in a borrowed tailcoat, in the widest trousers and without a single cufflink—in Moscow, such a groomsman would be kicked out, but here I was the most striking of all.

I saw rich brides. The choice is enormous, but I was so drunk the whole time that I mistook bottles for girls, and girls for bottles. Probably thanks to my drunken state, the local girls found me witty and ‘a joker.’ The girls here are a solid sheep: if one gets up and leaves the hall, the others will follow. One of them, the boldest and smartest, wanting to show that she too was not alien to delicate manners and politics, kept hitting my hand with her fan and saying: ‘Oh, you wretch!’, all the while maintaining a frightened expression on her face. I taught her to say to the gentlemen: ‘How naive you are!’

The newlyweds, probably due to local custom, kissed every minute, kissing so intensely that their lips made a crack from the compressed air every time, and I got a taste of cloying raisins in my mouth and a spasm in my left calf. From their kisses, the inflammation on my left leg got worse.”

To the Chekhovs. Cherkassk, April 25, 1887